Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1897

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 53.3 × 64.8 cm

- Location

- The National Gallery, London

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

The meaning of Boulevard Montmartre at Night is the conversion of darkness into a civic spectacle: electric arc lamps, gaslit shops, and cab lights reorder the night into a new system of visibility and desire 12. Pissarro shows how modern infrastructure—Haussmann’s boulevard and municipal lighting—absorbs individuals into a collective stream, where identity yields to velocity. It matters because the painting declares the city itself a time‑based organism; light, weather, and traffic become the real subject of Impressionism’s late phase 14. This is why Boulevard Montmartre at Night is important: it codifies the nocturnal city as a modern motif and demonstrates how painterly touch can differentiate technologies of light while conveying social experience 13.

From a vertiginous vantage near the Grand Hôtel de Russie, the boulevard funnels toward a hazed vanishing point, its flanking façades tapering like open jaws that swallow the crowd. Pissarro locks the composition with two parallel streams: a central bead‑string of cool white orbs and the warm, broken fires at shop level. The former parses as electric arc lamps—bluish, crisp, evenly spaced—while the latter are the buttery gaslit vitrines that pool on the pavement’s wet skin 12. The image insists on differences within modern light: the arc lamps register as cold constellations that punctuate civic order; the storefront yellows flare and sputter, tagging consumption and leisure. These rival temperatures meet on the rain-dark boulevard, where reflections double the lamps into wavering commas, making the street itself the city’s luminous organ. Pissarro paints the cab rank as a dotted procession of headlamps—small pricks of red, white, and yellow—queuing toward the Théâtre des Variétés, so that entertainment economics become visible as color grammar 1. The people and carriages are not described; they are counted by strokes. This refusal of portraiture is not a deficit but a thesis: in modern circulation, the unit is not the person but the flow. Brushwork completes the argument. Thick, short, directionally varied dabs break edges the way night does, turning description into sensation. The facades, swabbed in violets and bruised blues, shed their masonry and become atmospheric planes, while the boulevard’s slick center reads like a river of metal and light. That wetness is not meteorological filler; it is a device that multiplies the city’s artificial suns, showing how technology and weather collaborate to produce spectacle 12. Pissarro’s diagonal scaffolding—rooflines, tree row, lamp standards—stitches pedestrians and vehicles into a single vector that descends toward us, so the viewer is not outside the scene but caught in its forward pressure. This is a city organized for looking and moving, two forms of consumption that Impressionism turns into paint. In 1897, Pissarro serializes this motif across times and weathers; the nocturne is the key that proves the method, because only at night can light itself become both subject and structure 14. The arc lamp sequence establishes civic tempo; the gaslit shopfronts flare as private seductions; the cab lights code desire into transport logistics. Between them, the individual dissolves. Yet the picture resists cynicism. Its cool‑warm counterpoint stages a fragile pact between order and pleasure, bureaucracy and festivity. By letting the late‑evening blues swallow detail, Pissarro preserves the thrill of not knowing—of being subsumed by a crowd whose faces you cannot see but whose momentum you feel in the brush. The high view is not surveillance; it is empathy at a distance, a way to hold the city’s evanescence long enough to recognize it. That is the meaning of Boulevard Montmartre at Night: modernity is not only steel and policy; it is a choreography of lights whose reflections invent new kinds of time. And that is why Boulevard Montmartre at Night is important: it proves that Impressionism’s core claim—the primacy of perception in flux—can encompass the engineered night of the modern metropolis, distinguishing technologies of illumination in pigment while translating anonymity into rhythm 124.Citations

- National Gallery, London – Collection entry: The Boulevard Montmartre at Night

- National Gallery, London – Picture of the Month (April 2023)

- Art UK – The Boulevard Montmartre at Night

- Brettell, Richard R., and Joachim Pissarro, The Impressionist and the City: Pissarro’s Series Paintings (1992–93)

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – Camille Pissarro

- Art Institute of Chicago – Pissarro: Paintings and Works on Paper (Digital Scholarly Catalogue)

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Historical Context

Source: National Gallery, London

Formal Analysis

Source: National Gallery, London; Art Institute of Chicago; Brettell & Joachim Pissarro

Social Commentary

Source: National Gallery, London; Brettell & Joachim Pissarro

Biographical

Source: National Gallery, London; Britannica; Brettell & Joachim Pissarro; Art Institute of Chicago

Reception History

Source: National Gallery, London; Art UK; Brettell & Joachim Pissarro

Psychological Interpretation

Source: National Gallery, London

Related Themes

About Camille Pissarro

More by Camille Pissarro

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

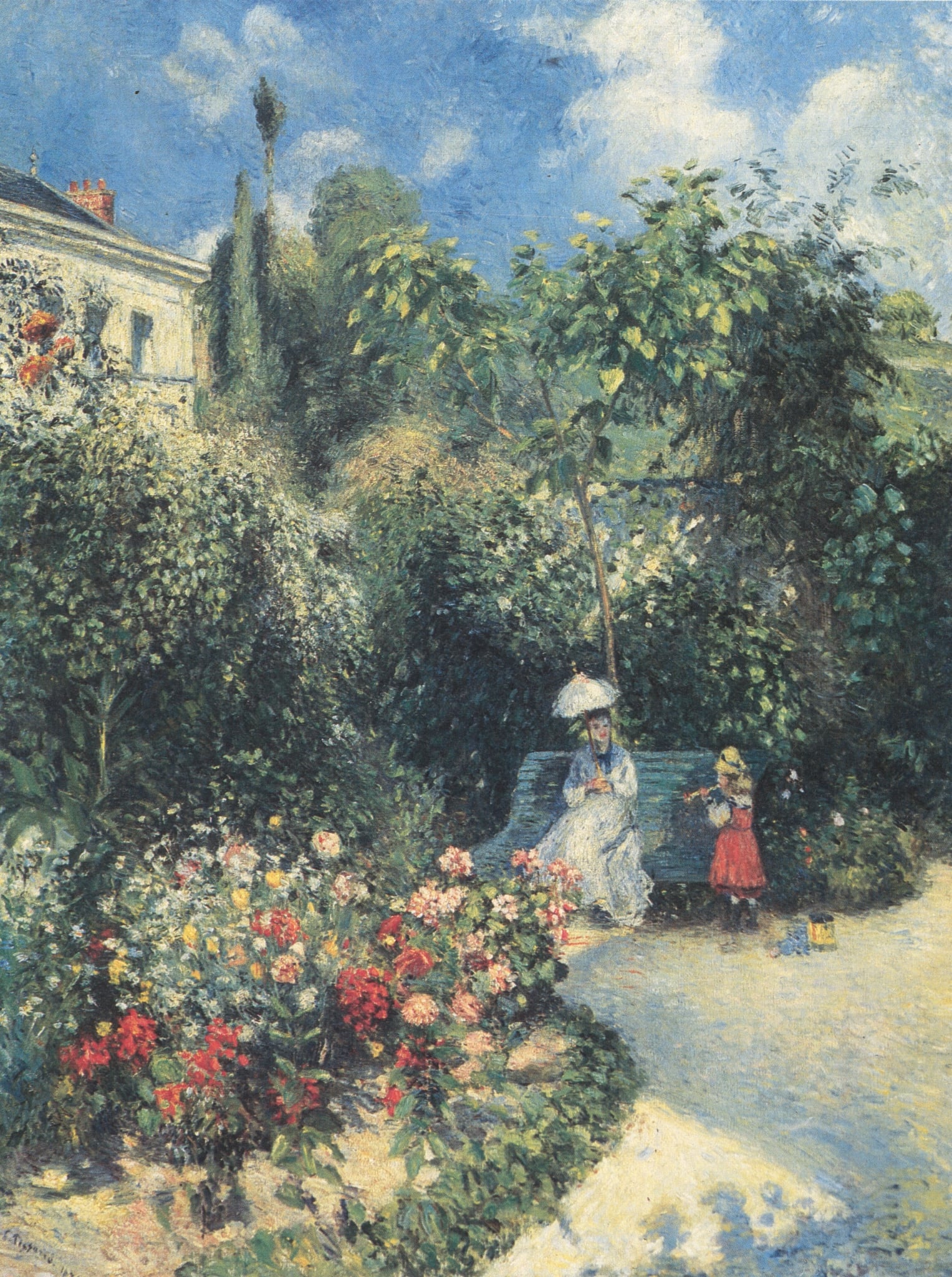

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.