Camille Pissarro

Biography

Themes in Their Work

Featured in Essays

Essay

The Courtesan Behind the Sword

Start in a rented room with a curtain pulled high. A banker is waiting for a deliverable; a patronage network is watching a comet of a painter. Caravaggio steps to the canvas and chooses his Judith — not a saint from a sermon, but a woman Rome’s police could name. “And she smote twice upon his neck, and cut off his head.” The Book of Judith gives the script. Caravaggio turns it into live theater.

Essay

The Day Manet Took a Knife to His Own Painting

Paris, 1864. The Salon is the arena. A painting can knight you or end you. Manet, already bruised by scandal the year before, bets big on spectacle: a sweeping bullfight scene, Spanish costume, blood and bravado. He hangs it for the crowd. The critics circle. The verdict is icy. He can’t afford another public drubbing; every jeer dents his chances of becoming more than a punchline. The stakes are career, pride, and Paris itself. Here’s the twist sitting in plain sight: the famous close‑up of the fallen matador you know as The Dead Toreador — you can see it here [link](/artworks/edouard-manet/the-dead-toreador)[1] — started life as just one corner of that doomed panorama.

Essay

The Iron and the Eye: Degas Against the Glare

By the mid‑1870s, collectors wanted Degas for ballet: satin shoes, mirrored studios, the sellable dream. Instead, he kept showing up in steam and starch. Over and over, he painted laundresses—women who boiled, beat, and pressed other people’s clothes for pennies in rooms as hot as kilns. The choice wasn’t neutral; it could stall sales and annoy patrons who preferred dancers to drudgery. But Degas wouldn’t look away. The Musée d’Orsay calls this an obsession, tracing versions of ironers across the decade, including the famous yawning pair in Repasseuses [1].

Essay

The Blue Armchair Rebellion

Paris, 1878. An American woman is fighting for entry into the most controversial circle in art. Reputation on the line, money scarce, critics circling. Her next move must land. She paints… a kid who won’t behave. A small girl slumps diagonally across a vast sea of turquoise upholstery, socks rumpled, gaze elsewhere, a terrier comatose on a neighboring chair. It looks unbothered, even rude. And that’s the point. In a market that rewarded sugarcoated childhood, Mary Cassatt risked everything on a portrait that shrugs at adult decorum [1]. Cassatt had just thrown in with the outsiders—at Degas’s urging—and was preparing for her first Impressionist exhibition the following year. It wasn’t a club you entered softly. “I accepted with joy,” she later said of the invitation, because the Salon “crushed all originality” [3]. If this picture failed, the doubters would say she didn’t belong.

Essay

The Balcony That Started a Riot

Picture the stakes. Paris still bowed to the Salon, a jury that could mint careers or erase them. Monet had a young family, debts, and a dwindling market. So he and a handful of friends did the unthinkable: rent the grand studio of star photographer Nadar at 35 Boulevard des Capucines and hang their own show—no permission, no jury, all risk. The vantage in this painting is that balcony, that window, that leap.[2][7]

Essay

Degas’s Vanished Paris: The Painting That Went to War and Came Back With a Secret

Start in 1875: a man strides, girls in gray keep pace, a dog scouts the pavement. No one looks at each other. A city square yawns like a stage. Edgar Degas freezes it all with brutal cuts at the frame, the visual grammar of a world too fast for eye contact. Today the canvas lives at the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, a long way from the Paris square it depicts—and even farther from where it was last seen before the war [State Hermitage Museum](https://hermitagemuseum.org/digital-collection/29681?lng=en)[1].

Essay

The Audition in Blue: Renoir’s Gamble Behind Girl with a Watering Can

Picture Renoir at 35, debts circling, reputation wobbling after the second Impressionist show. The critics mocked his circle; the market yawned. Portrait commissions — the cash engine of Paris — kept going to establishment names. He had to change that or sink. [National Gallery, London](https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/pierre-auguste-renoir) [2].

Essay

The Picnic That Made an Emperor Blink

Start with the stakes: the Paris Salon decided an artist’s fate. Win the jury, you get buyers, critics, immortality. Lose, you vanish. That year, the jury rejected an unusually high number of submissions. Among the refusés was a picnic with a stare that wouldn’t look away—Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, then called Le Bain. The museum that owns it now says flatly: it “caused a scandal.” [Musée d’Orsay](https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/le-dejeuner-sur-lherbe-904) [1].

Essay

She Put Down the Fan

Look closely: the props of flirtation lie useless in the grass. The fan is shut. The green parasol is abandoned. A carriage blurs by in the distance, but the figure never looks up. She reads, and the world waits. Morisot painted this in 1873, her surface quick and alive, the scene almost dissolving around the reader’s concentration. The Cleveland Museum of Art calls it Reading; it’s small, disarming, and dangerously calm [2].

Essay

Renoir’s Fake Date Night

Picture the stakes: Renoir is thirty-three, broke, and rolling the dice on a renegade show the Salon has snubbed—the first Impressionist exhibition. If this painting doesn’t spark attention, he’s not just unfashionable; he’s finished.

Essay

The Sunniest Monet Was Painted in a Storm

First glance: a perfect day. Parasols tilt. White sails cut the Channel. Sun freckles the water like confetti. It looks like a rich man’s postcard. That’s the trap.

Essay

Monet’s Pink Parasol, and the Secret It Was Hiding

Start at the edge. In 1882 Monet escaped to a fishing village on the Normandy coast and worked like a man trying to outrun gossip. He had fallen in love with Alice Hoschedé, the wife of his former patron Ernest, whose finances had collapsed. Two households had fused into one. The art world was watching, and not kindly [4].

Essay

The Night Pissarro Learned to See Again

He was in his mid‑sixties, the elder statesman of Impressionism with bills to pay and younger stars sprinting past. Critics loved the myth of Pissarro the tireless outdoor painter. But his reality was uglier: an infection had made bright, dusty daylight brutal. So he moved indoors and up—into a rented high window on the Boulevard Montmartre—staking his reputation on whether a man who couldn’t face the sun could still paint light.[5]

Essay

The Mirror That Said No: Berthe Morisot’s Quiet Rebellion

Look at the setup: a woman in satin, arm lifted, powders and jars within reach. Paris, late 1870s. It reads like flirtation. But the reflection is a smear, the face withheld. Morisot built a trap for the viewer and sprung it with a brush.

Essay

The Pink Portrait the Revolution Seized

Start in 1877. Renoir is broke, ambitious, and tired of being called a lightweight. He paints a young actress from the Comédie‑Française—Jeanne Samary—with a coral-pink atmosphere and a sea‑green dress, a portrait designed to charm the Salon and the paying classes. The picture glows like a debutante’s rumor. It still does. See it up close on our artwork page: /artworks/pierre-auguste-renoir/portrait-of-jeanne-samary.

Essay

The Prettiest SOS on the Seine

Picture Renoir at thirty-four, rent due, reputation wobbling. He’s fresh from the first Impressionist shockwaves and a Paris press that mocked his friends as incompetents. One reviewer sneered that Renoir painted a woman’s body like “a mass of decomposing flesh with green and purple spots.”[4] The message was clear: stop, or starve.

Essay

The Wheatfield Myth: Van Gogh’s Stormiest Painting Isn’t a Suicide Note

Scroll any feed and you’ll meet this image: a blasted-blue sky, a road that forks and dies, black birds like shrapnel. The caption is almost always the same: his last canvas, his farewell. Our shiver becomes the story.

Essay

Renoir’s Sweetest Breakup

You know this image: a couple under a living arbor, hands grazing over a café table. Soft light. Soft edges. Soft story. Except the year is 1885, and Pierre‑Auguste Renoir is in crisis. The painter who helped spark Impressionism is suddenly telling friends he no longer knows how to paint. The romance on canvas hides a rupture off it.[3][10]

Essay

The Day Monet Turned a Picnic into a Comeback

Start here: a hill at Argenteuil, a flash of white dress, a boy blinking in the wind. The painting feels tossed-off and weightless. That’s the trick. Because months earlier, the money and the mood were brutal. In 1875, fresh from the first Impressionist exhibition’s ridicule, Monet and friends tried an auction at Hôtel Drouot. The crowd jeered, prices collapsed, and police were called. His name became shorthand for recklessness with paint, not value. The family’s comfort—rent, food, even paint—was on the line. The parasol wasn’t shade; it was cover. Monet needed an image that could flip the narrative: not starving bohemians, but modern life, bright and breathable, the very leisure new suburban rail lines were selling. Argenteuil was Paris’s weekend playground—sailboats, strolls, picnics, and status on display—exactly the world collectors fancied seeing on their walls.

Essay

The Cradle Was a Warning, Not a Lullaby

Paris, 1874. A young painter stakes her reputation on a domestic scene while her comrades hang boats, boulevards, and fog. Berthe Morisot chooses a nursery. Money, credibility, and a seat at the table are on the line—because if the public writes her off as merely “feminine,” she’s finished.

Essay

The Cathedral That Took Monet Hostage

The postcard version is easy: stone lace, soft color, Impressionism behaving. But Monet’s cathedral wasn’t decor. It was a duel with the sun, run on minutes and panic, with a dealer betting that the public would finally understand what Impressionism had been saying all along.

Essay

The Woman Paris Refused to See

The Salon was the only career ladder that mattered. Manet needed it. Respectability, buyers, a future—hung on a wall in 1865. Then the crowd arrived, and the painting that wouldn’t behave drew jeers so thick the museum put up a cord to protect it. The Musée d’Orsay is blunt about the reception: scandal, fury, and a guard between public and paint.

Essay

The $65 Million Spring

Christie’s, New York, 2014. Phones light up. The bidding climbs past the price of many houses, then many museums’ annual acquisitions budgets. When the hammer falls, Manet’s Jeanne (Spring) shatters a record and the Getty wins the picture for $65.1 million—a new pinnacle for the artist at auction [3][1].

Essay

The Night Degas Put the Ballerinas in the Back Row

Picture Paris in the late 1860s: velvet boxes, diamonded patrons, ballerinas floating like chandeliers. And then an unknown painter plants his easel where no one is looking—down in the orchestra pit. Why risk it? Because reputation was on the line. Degas was switching gears, ditching history painting for modern life, and the Opéra was the city’s most ruthless stage: art, money, and gossip in a single address.[1] If he chose wrong, he’d stay a nobody. He also had a personal stake. The man gripping that diagonal bassoon is Désiré Dihau—a real friend, a working musician whose salary depended on staying visible to an audience that never looked his way.[2][3] Degas knew the rules of this house, and he was about to break them on canvas.

Essay

Monet’s Quiet Bridge, Built on Noise

In 1893, Monet walked into local bureaucracy with a radical request: let me reroute a stream and build a lily pond in my backyard. Farmers objected, fearing floods and foreign plants. The painter pushed through anyway, secured permission, and set about reshaping the land at Giverny. The tranquil bridge you know was born out of paperwork and protests, not Zen stillness. [1] Money and reputation were on the line. Monet had finally bought his home in 1890 after years of financial precarity; now he was risking cash and goodwill to turn a garden into a studio—and a studio into a legacy. He wasn’t just planting; he was betting his name. He staged the scene with precision: a curved wooden span, no horizon, and a pond thick with lilies. This wasn’t picturesque chance—it was design. The bridge, lifted from the era’s mania for Japan, signaled a fashionable cool while tightening the composition like a drum. As the National Gallery in London notes, the structure arrived alongside Paris’s craze for Japanese art and prints, which Monet collected obsessively. [2] Then came the first payoff: in 1899, he painted it. If you think the image recorded a walk in the park, consider how hard he worked to make the park exist. The Japanese Footbridge compresses space, removes the sky, and turns reflection into theater, a trick he could repeat at will from his doorstep. [1] [5]

Essay

The Prettiest Sunset in Art Was Air Pollution

He arrived not for Parliament’s Gothic drama but for the weather report. From a window on the south bank, Monet lined up the towers and waited for the sky to burn through the haze. The National Gallery of Art notes he finished the canvas in 1903, after returning to Giverny to tune the color of the Thames like a violin string—then unveiled the London series in 1904, betting his mature reputation on a city that barely wanted to be seen at all. [NGA link][1]

Essay

Monet Booked the Steam

Monet was in his late thirties and still not a sure thing. The Impressionists had split with the Salon, but the public wasn’t buying in bulk. He needed a subject that felt undeniable—modern, popular, unmistakably Paris. He picked the engine room of the city itself: the Gare Saint-Lazare, the Western Railway’s iron-and-glass cathedral of departures.

Essay

Grit in the Light: Monet’s Trouville, Captured Not Just Seen

Stand before the National Gallery’s Beach at Trouville and the composition immediately leans into you: a boardwalk pulled taut on the diagonal, parasols opening like sails, and a regiment of red flags firing toward the Channel. The confection of hotels to the right—anchored by the fashionable Hôtel des Roches Noires—presses the promenade into a stage for modern leisure, a Second Empire theater of strolling and display. Monet painted it on site in the summer of 1870, a blustery day made legible by architecture and cloth rather than narrative incident, as the museum’s entry for the work recounts ([The Beach at Trouville](https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-the-beach-at-trouville) [1]). [Image: Beach at Trouville (1870) — /artworks/claude-monet/beach-at-trouville] That slanted boardwalk does more than guide the eye: it sets a vector. From left surf to right-hand steps, every stroke queues to the wind’s push, a coastal physics lesson rendered in broken blues and bleached ochres.

Essay

The Wind Is the Protagonist: Monet’s Beach at Trouville as a Pre-Digital Live Feed

Beach at Trouville looks, at first glance, like a souvenir of a fashionable afternoon: sun-struck planks, white parasols, genteel promenaders. But every element is drafted into a single task—measuring the air. The diagonal boardwalk hurries the eye past the figures; a volley of red flags snaps mid-gust; skirts and veils flare into vectors. In Monet’s 1870 season at the Normandy resort, modern leisure had met meteorology—tourism built to be felt in motion [2][4]. [Artwork: /artworks/claude-monet/beach-at-trouville] That sense of motion anchors the canvas in a specific place and moment. Trouville had exploded into a Second Empire playground, its grand hotels and villas marching right up to the sand. Monet painted those very facades elsewhere that same season, including the newly fashionable Hôtel des Roches Noires—a statement of seaside modernity still rising from the dunes [1].

Featured Artworks

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Camille Pissarro (1897)

A high window turns Paris into a flowing current: in Boulevard Montmartre at Night, Camille Pissarro fuses <strong>modern light</strong> and <strong>urban movement</strong> into a single, restless rhythm. Cool electric halos and warm gaslit windows shimmer across rain‑slick stone, where carriages and crowds dissolve into <strong>pulse-like blurs</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

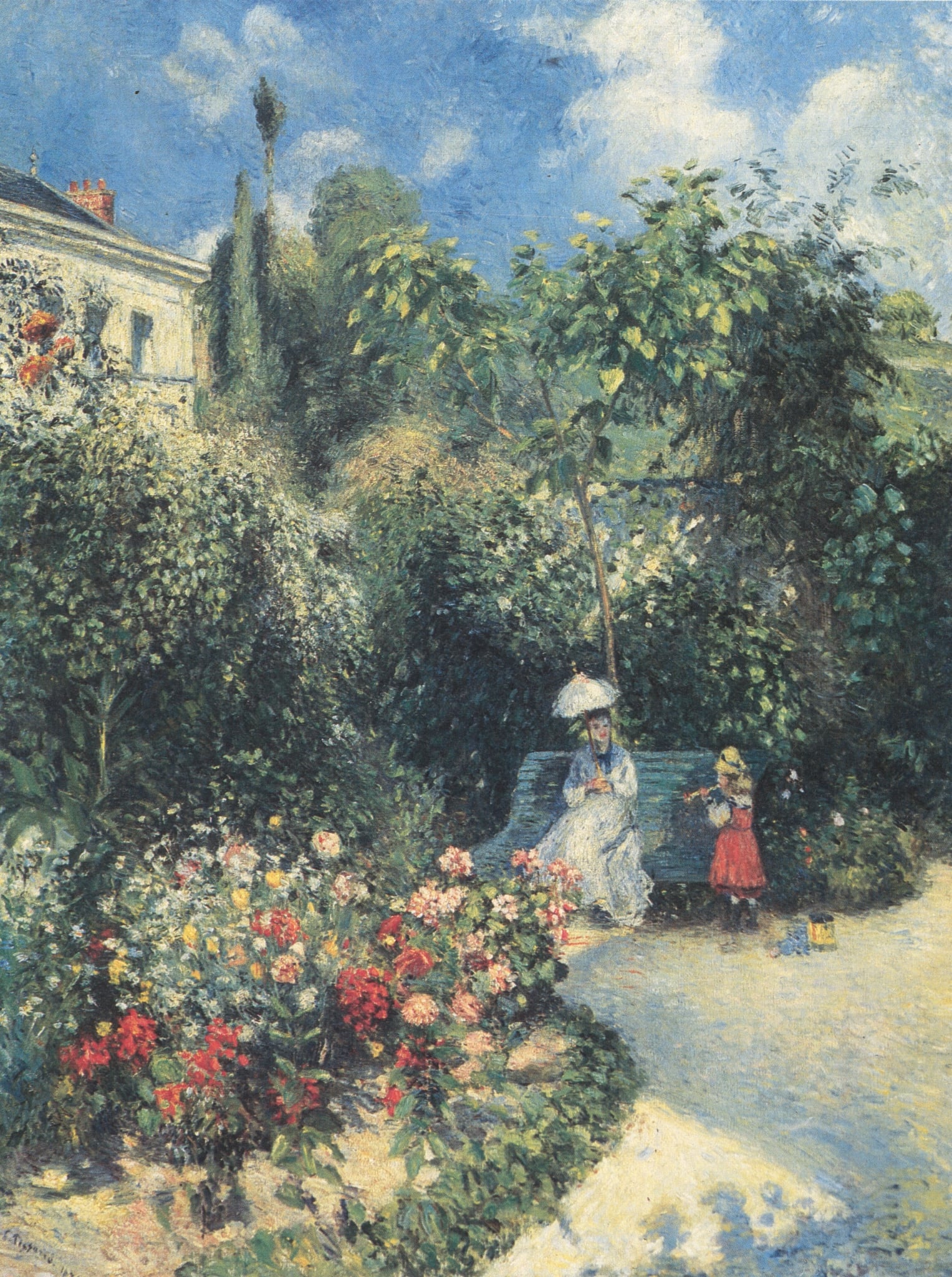

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.