The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1897

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 64.8 × 81.3 cm

- Location

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Seriality & Temporality

Source: National Gallery of Victoria (NGV)

Optical/Technical Analysis

Source: National Gallery (London) and The Met Heilbrunn Timeline

Sociology of the Crowd (Flâneur from Above)

Source: The Met Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Weather as Chronometer

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica and NGV

Historical/Political Context

Source: Smarthistory

Related Themes

About Camille Pissarro

More by Camille Pissarro

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Camille Pissarro (1897)

A high window turns Paris into a flowing current: in Boulevard Montmartre at Night, Camille Pissarro fuses <strong>modern light</strong> and <strong>urban movement</strong> into a single, restless rhythm. Cool electric halos and warm gaslit windows shimmer across rain‑slick stone, where carriages and crowds dissolve into <strong>pulse-like blurs</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

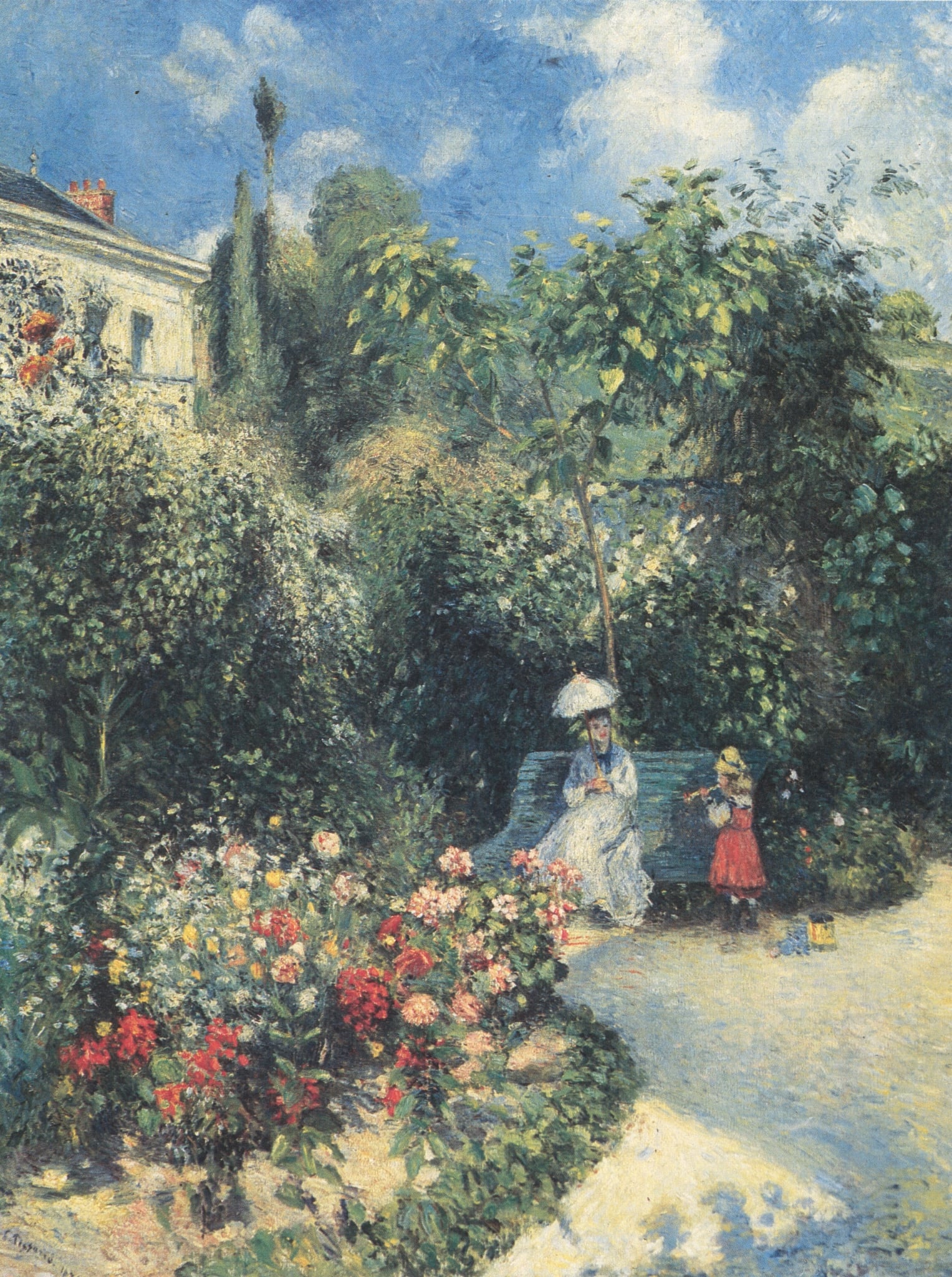

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.