Everyday life as art (readymade, the ordinary)

Featured Artworks

View of Delft

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1660–1661)

View of Delft turns a faithful city prospect into a meditation on <strong>civic order, resilience, and time</strong>. Beneath a low horizon, drifting clouds cast mobile shadows while shafts of sun ignite blue roofs and the bright spire of the <strong>Nieuwe Kerk</strong>, holding the scene’s moral center <sup>[1]</sup>. Small figures and moored boats ground prosperity in <strong>everyday community</strong> without breaking the hush.

The Tea

Mary Cassatt (about 1880)

Mary Cassatt’s The Tea stages a poised, interior <strong>drama of manners</strong>: two women sit close yet feel apart, one thoughtful, the other raising a cup that <strong>veils her face</strong>. A gleaming, oversized <strong>silver tea service</strong> commands the foreground, its reflections turning ritual objects into actors in the scene <sup>[1]</sup>. The shallow, cropped room—striped wall, gilt mirror, marble mantel—compresses the atmosphere into <strong>intimacy edged by restraint</strong>.

Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore

Mary Cassatt (c. 1886)

Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore distills childhood into a quiet drama of <strong>interiority</strong> and <strong>constraint</strong>. The oversized straw hat and plain pinafore bracket a flushed face, downcast eyes, and <strong>clasped hands</strong>, turning a simple pose into a study of modern self‑consciousness <sup>[1]</sup>. Cassatt’s cool grays and swift, luminous strokes make mood—not costume—the subject.

Breakfast in Bed

Mary Cassatt (1897)

Breakfast in Bed distills a <strong>tender modern intimacy</strong> into a tightly cropped sanctuary of rumpled white linens, protective embrace, and interrupted routine. Mary Cassatt uses <strong>cool light</strong> against <strong>warm flesh</strong> to anchor attention on the mother’s encircling arm and the child’s outward gaze, fusing care, curiosity, and the rhythms of <strong>everyday modern life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Embroiderer

Johannes Vermeer (1669–1670)

In The Embroiderer, Johannes Vermeer condenses a world of work into a palm‑sized drama of <strong>attention</strong> and <strong>transformation</strong>. A young woman bends over a lace pillow as loose red and white threads spill in front, while a nascent pattern gathers under her poised fingers. Vermeer’s right‑hand light isolates the act of making and turns domestic labor into <strong>virtuous concentration</strong> <sup>[1]</sup>.

![Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] by Andy Warhol](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.googleapis.com%2Fsite-images-programmatic%2Fpaintings%2F1771915343451-6gzg8m.jpg&w=3840&q=85)

Triple Elvis [Ferus Type]

Andy Warhol (1963)

In Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963), Andy Warhol multiplies a gunslinging movie idol across a cool, metallic field, turning a singular persona into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>. The sharply printed figure at center flanked by fading, <strong>ghosted</strong> doubles collapses still image, filmic motion, and mass reproduction into one charged surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Café Terrace at Night

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

In Café Terrace at Night, Vincent van Gogh turns nocturne into <strong>luminous color</strong>: a gas‑lit terrace glows in yellows and oranges against a deep <strong>ultramarine sky</strong> pricked with stars. By building night “<strong>without black</strong>,” he stages a vivid encounter between human sociability and the vastness overhead <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Pont Neuf Paris

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1872)

In Pont Neuf Paris, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns the oldest bridge in Paris into a stage where <strong>light</strong> and <strong>movement</strong> bind a city back together. From a high perch, he orchestrates crowds, carriages, gas lamps, the rippling Seine, and a fluttering <strong>tricolor</strong> so that everyday bustle reads as civic grace <sup>[1]</sup>.

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt

Mary Cassatt (1884)

A quiet, domestic tableau becomes a study in <strong>authority tempered by affection</strong>. In Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, Mary Cassatt fuses father and child into a single dark silhouette against a luminous, brushed interior, their shared gaze fixed beyond the frame. The <strong>newspaper</strong>, <strong>linked hands</strong>, and <strong>cropped closeness</strong> transform a routine moment into a symbol of generational continuity and modern attentiveness.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

Poppies

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Poppies (1873) turns a suburban hillside into a theater of <strong>light, time, and modern leisure</strong>. A red diagonal of poppies counters cool fields and sky, while a woman with a <strong>blue parasol</strong> and a child appear twice along the slope, staging a gentle <strong>echo of moments</strong> rather than a single event <sup>[1]</sup>. The painting asserts sensation over contour, letting broken touches make the day itself the subject.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Child's Bath

Mary Cassatt (1893)

Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (1893) recasts an ordinary ritual as <strong>modern devotion</strong>. From a steep, print-like vantage, interlocking stripes, circles, and diagonals focus attention on <strong>touch, care, and renewal</strong>, turning domestic labor into a subject of high art <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The work synthesizes Impressionist sensitivity with <strong>Japonisme</strong> design to monumentalize the private sphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Vase of Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1889)

Vase of Flowers is a late‑1880s still life in which Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a humble blue‑green jug and a tumbling bouquet into a <strong>laboratory of color and touch</strong>. Against a warm ocher wall and reddish tabletop, coral and vermilion blossoms flare while cool greens and violets anchor the mass, letting <strong>color function as drawing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The work affirms Renoir’s belief that flower painting was a space for bold experimentation that fed his figure art.

The Floor Scrapers

Gustave Caillebotte (1875)

Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers stages three shirtless workers planing a parquet floor as shafts of light pour through an ornate balcony door. The painting fuses <strong>rigorous perspective</strong> with <strong>modern urban labor</strong>, turning curls of wood and raking light into a ledger of time and effort <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. Its cool, gilded interior makes visible how bourgeois elegance is built on bodily work.

Woman at Her Toilette

Berthe Morisot (1875–1880)

Woman at Her Toilette stages a private ritual of self-fashioning, not a spectacle of vanity. A woman, seen from behind, lifts her arm to adjust her hair as a <strong>black velvet choker</strong> punctuates Morisot’s silvery-violet haze; the <strong>mirror’s blurred reflection</strong> with powders, jars, and a white flower refuses a clear face. Morisot’s <strong>feathery facture</strong> turns a fleeting toilette into modern subjectivity made visible <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Dance in the Country

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

Dance in the Country shows a couple swept into a close embrace on a café terrace, their bodies turning in a soft spiral as foliage and sunlight dissolve into <strong>dappled color</strong>. Renoir orchestrates <strong>bourgeois leisure</strong>—the tossed straw boater, a small table with glass and napkin, the woman’s floral dress and red bonnet—to stage a moment where decorum and desire meet. The result is a modern emblem of shared pleasure, poised between Impressionist shimmer and a newly <strong>firm, linear touch</strong>.

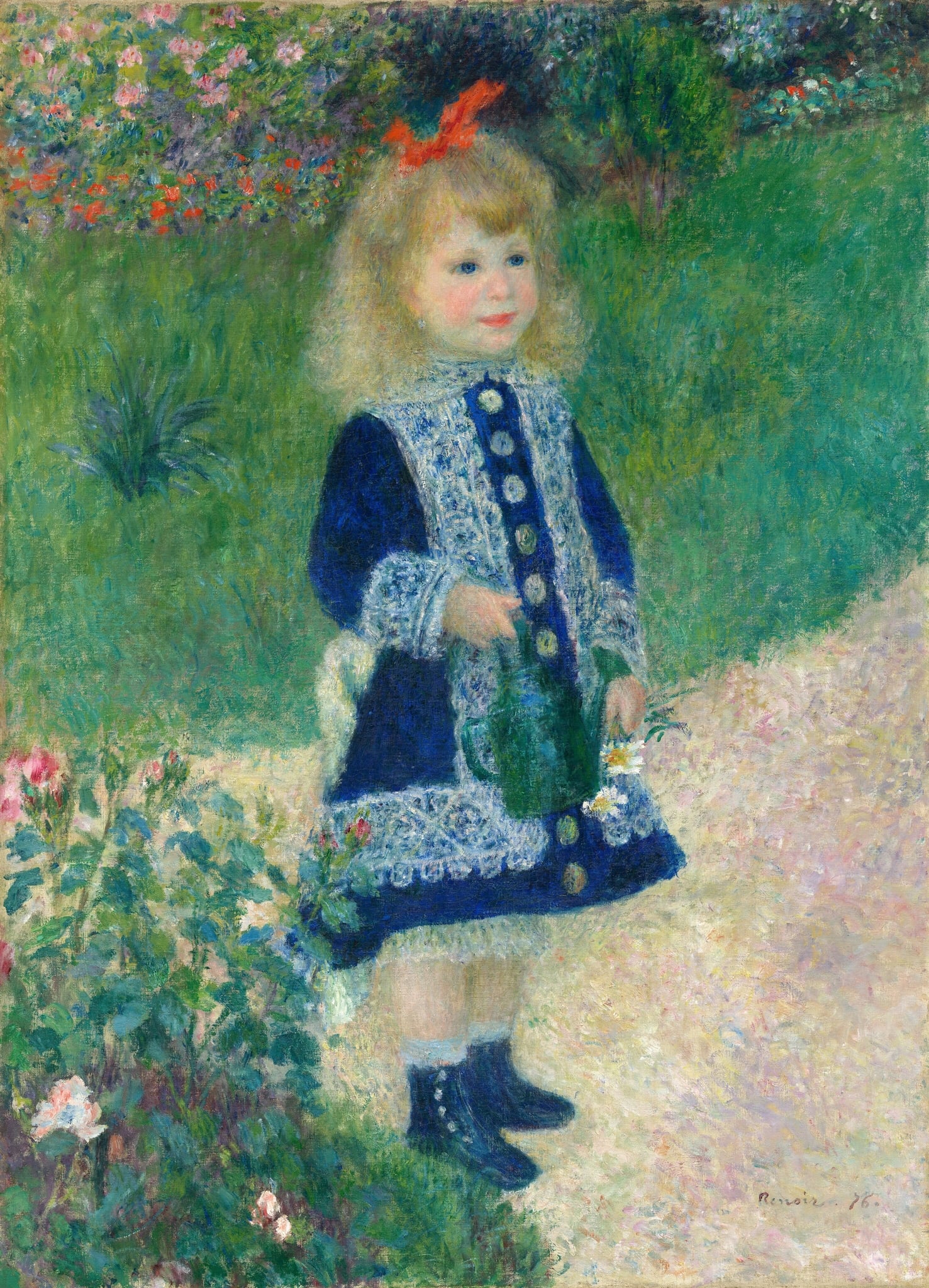

Girl with a Watering Can

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

Renoir’s 1876 Girl with a Watering Can fuses a crisply perceived child with a dissolving garden atmosphere, using <strong>prismatic color</strong> and <strong>controlled facial modeling</strong> to stage innocence within modern leisure <sup>[1]</sup>. The cobalt dress, red bow, and green can punctuate a haze of pinks and greens, making nurture and growth the scene’s quiet thesis.

Combing the Hair

Edgar Degas (c.1896)

Edgar Degas’s Combing the Hair crystallizes a private ritual into a scene of <strong>compressed intimacy</strong> and <strong>classed labor</strong>. The incandescent field of red fuses figure and room, turning the hair into a <strong>binding ribbon</strong> between attendant and sitter <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Basket of Apples

Paul Cézanne (c. 1893)

Paul Cézanne’s The Basket of Apples stages a quiet drama of <strong>balance and perception</strong>. A tilted basket spills apples across a <strong>rumpled white cloth</strong> toward a <strong>dark vertical bottle</strong> and a plate of <strong>biscuits</strong>, while the tabletop’s edges refuse to align—an intentional play of <strong>multiple viewpoints</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Still Life with Apples and Oranges

Paul Cézanne (c. 1899)

Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples and Oranges builds a quietly monumental world from domestic things. A tilting table, a heaped white compote, a flowered jug, and cascading cloths turn fruit into <strong>durable forms</strong> stabilized by <strong>color relationships</strong> rather than single‑point perspective <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The result is a still life that feels both solid and subtly <strong>unstable</strong>, a meditation on how we construct vision.

Bathers at Asnières

Georges Seurat (1884)

Bathers at Asnières stages a scene of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine, where workers recline and wade beneath a hazy, unified light. Seurat fuses <strong>classicizing stillness</strong> with an <strong>industrial backdrop</strong> of chimneys, bridges, and boats, turning ordinary rest into a monumental, ordered image of urban life <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The canvas balances soft greens and blues with geometric structures, producing a calm yet charged harmony.

The Cup of Tea

Mary Cassatt (ca. 1880–81)

Mary Cassatt’s The Cup of Tea distills a moment of bourgeois leisure into a study of <strong>poise</strong>, <strong>etiquette</strong>, and <strong>private reflection</strong>. A woman in a rose‑pink dress and bonnet, white‑gloved, balances a gold‑rimmed cup against the shimmer of <strong>Impressionist</strong> brushwork, while a green planter of pale blossoms echoes her pastel palette <sup>[1]</sup>. The work turns an ordinary ritual into a modern emblem of women’s experience.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Reading

Berthe Morisot (1873)

In Berthe Morisot’s <strong>Reading</strong> (1873), a woman in a pale, patterned dress sits on the grass, absorbed in a book while a <strong>green parasol</strong> and <strong>folded fan</strong> lie nearby. Morisot’s quick, luminous brushwork dissolves the landscape into <strong>atmospheric greens</strong> as a distant carriage passes, turning an outdoor scene into a study of interior life. The work makes <strong>female intellectual absorption</strong> its true subject, aligning modern leisure with private thought.

Camille Monet on a Garden Bench

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Camille Monet on a Garden Bench (1873) stages an intimate pause where <strong>light, grief, and modern leisure</strong> intersect. Camille, shaded and withdrawn, holds a letter while a <strong>top‑hatted neighbor</strong> hovers; a bright bank of <strong>red geraniums</strong> and a strolling woman with a parasol ignite the distance <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet converts a domestic garden into a scene about <strong>psychological distance</strong> amid fleeting sunlight.

Lady at the Tea Table

Mary Cassatt (1883–85 (signed 1885))

Mary Cassatt’s Lady at the Tea Table distills a domestic rite into a scene of <strong>quiet authority</strong>. The sitter’s black silhouette, lace cap, and poised hand marshal a regiment of <strong>cobalt‑and‑gold Canton porcelain</strong>, while tight cropping and planar light convert hospitality into <strong>modern self‑possession</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Still Life with Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers (1885) sets a jubilant bouquet in a pale, crackled vase against softly dissolving wallpaper and a wicker screen. With quick, clear strokes and a centered, oval mass, the painting unites <strong>Impressionist color</strong> with a <strong>classical, post-Italy structure</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The slight droop of blossoms turns the domestic scene into a gentle <strong>vanitas</strong>—a savoring of beauty before it fades <sup>[5]</sup>.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper (1942)

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks turns a corner diner into a sealed stage where <strong>fluorescent light</strong> and <strong>curved glass</strong> hold four figures in suspended time. The empty streets and the “PHILLIES” cigar sign sharpen the sense of <strong>urban solitude</strong> while hinting at wartime vigilance. The result is a cool, lucid image of modern life: illuminated, open to view, and emotionally out of reach.

The Gleaners

Jean-Francois Millet (1857)

Three peasant women bend in a solemn rhythm, gleaning leftover stalks under a dry, late-afternoon light. In the far distance, tiny carts, haystacks, and an overseer on horseback signal abundance and authority, while the foreground figures loom with <strong>monumental gravity</strong>, asserting the dignity of labor amid inequality <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child

Mary Cassatt (1880)

Mary Cassatt’s Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child (1880) turns an ordinary bedtime ritual into a scene of <strong>caregiving, labor, and modern intimacy</strong>. Cropped close, with the child’s legs diagonally splayed and a tilted washbowl at the mother’s knee, the picture translates domestic routine into a <strong>modern Madonna</strong> for the bourgeois interior. Its flickering blues and milky whites, plus patterned upholstery and wallpaper, signal Cassatt’s <strong>Impressionist</strong> and japonisme-inflected design sense <sup>[2]</sup>.

Campbell's Soup Cans

Andy Warhol (1962)

Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans turns a shelf-staple into <strong>art</strong>, using a gridded array of near-identical red-and-white cans to fuse <strong>branding</strong> with <strong>painting</strong>. By repeating 32 flavors—Tomato, Clam Chowder, Chicken Noodle, and more—the work stages a clash between <strong>mass production</strong> and the artist’s hand <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror)

Mary Cassatt (ca. 1899)

Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror) turns a routine act of care into a <strong>modern icon</strong>. An oval mirror <strong>haloes</strong> the child while interlaced hands and close bodies make <strong>touch</strong> the vehicle of meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Milkmaid

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1660)

In The Milkmaid, Vermeer turns an ordinary act—pouring milk—into a scene of <strong>quiet monumentality</strong>. Light from the left fixes the maid’s absorbed attention and ignites the <strong>saturated yellow and blue</strong> of her dress, while the slow thread of milk becomes the image’s pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Bread, a Delft jug, nail holes, and a small <strong>foot warmer</strong> anchor a world where humble work is endowed with dignity and latent meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

La Grenouillère

Claude Monet (1869)

Monet’s La Grenouillère crystallizes the new culture of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine: crowded bathers, promenading couples, and rental boats orbit a floating resort. With <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a high-key palette, Monet turns water, light, and movement into the true subjects, suspending the scene at the brink of dissolving.