Mortality & transience (memento mori)

Featured Artworks

View of Delft

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1660–1661)

View of Delft turns a faithful city prospect into a meditation on <strong>civic order, resilience, and time</strong>. Beneath a low horizon, drifting clouds cast mobile shadows while shafts of sun ignite blue roofs and the bright spire of the <strong>Nieuwe Kerk</strong>, holding the scene’s moral center <sup>[1]</sup>. Small figures and moored boats ground prosperity in <strong>everyday community</strong> without breaking the hush.

The Thames below Westminster

Claude Monet (about 1871)

Claude Monet’s The Thames below Westminster turns London into <strong>light-made architecture</strong>, where Parliament’s mass dissolves into mist and the river shivers with <strong>industrial motion</strong>. Tugboats, a timber jetty with workers, and the rebuilt Westminster Bridge assert a modern city whose power is felt through atmosphere more than outline <sup>[1]</sup>.

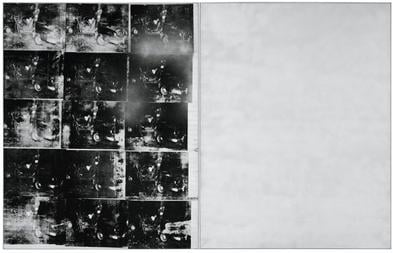

Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)

Andy Warhol (1963)

Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) pairs a grid of uneven, black‑and‑white silkscreened crash images with a vast, nearly blank field of metallic silver, staging a battle between <strong>relentless spectacle</strong> and <strong>mute void</strong>. Warhol’s industrial repetition converts tragedy into a consumable pattern while the reflective panel withholds detail, forcing viewers to face the limits of representation and the cold afterglow of modern media <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Women in the Garden

Claude Monet (1866–1867)

Claude Monet’s Women in the Garden choreographs four figures in a sunlit bower to test how <strong>white dresses</strong> register <strong>dappled light</strong> and shadow. The path, parasol, and clipped flowers frame a modern ritual of leisure while turning fashion into an instrument of <strong>perception</strong>. The scene reads less as portraiture than as a manifesto for painting the <strong>momentary</strong> outdoors <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Eight Elvises

Andy Warhol (1963)

A sweeping frieze of eight overlapping, gun‑drawn cowboys marches across a silver field, their forms slipping and ghosting as if frames of a film. Warhol converts a singular star into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>, where <strong>mechanical misregistration</strong> and life‑size scale turn bravado into spectacle <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Bacchus

Caravaggio (c. 1598)

Caravaggio’s Bacchus stages a human-scaled god who offers wine with disarming immediacy, yoking <strong>sensual invitation</strong> to <strong>vanitas</strong> warning. The tilted goblet, blemished fruit, and wilting leaves insist that abundance and youth are <strong>precarious</strong>. A private Roman milieu under Cardinal del Monte shaped this refined, provocative image <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

![Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] by Andy Warhol](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.googleapis.com%2Fsite-images-programmatic%2Fpaintings%2F1771915343451-6gzg8m.jpg&w=3840&q=85)

Triple Elvis [Ferus Type]

Andy Warhol (1963)

In Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963), Andy Warhol multiplies a gunslinging movie idol across a cool, metallic field, turning a singular persona into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>. The sharply printed figure at center flanked by fading, <strong>ghosted</strong> doubles collapses still image, filmic motion, and mass reproduction into one charged surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Turquoise Marilyn

Andy Warhol (1964)

In Turquoise Marilyn, Andy Warhol converts a movie star’s face into a <strong>modern icon</strong>: a tightly cropped head floating in a flat <strong>turquoise</strong> field, its <strong>acidic yellow hair</strong>, turquoise eye shadow, and <strong>lipstick-red</strong> mouth stamped by silkscreen’s mechanical bite. The slight <strong>misregistration</strong> around eyes and hair produces a halo-like tremor, fusing <strong>glamour and ghostliness</strong> to expose celebrity as a manufactured surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Giverny

Claude Monet (1900)

In The Artist's Garden at Giverny, Claude Monet turns his cultivated Clos Normand into a field of living color, where bands of violet <strong>irises</strong> surge toward a narrow, rose‑colored path. Broken, flickering strokes let greens, purples, and pinks mix optically so that light seems to tremble across the scene, while lilac‑toned tree trunks rhythmically guide the gaze inward <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Water Lilies

Claude Monet (1899)

<strong>Water Lilies</strong> centers on an arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> suspended over a pond where lilies and rippling reflections fuse into a single, vibrating surface. Monet turns the scene into a study of <strong>perception-in-flux</strong>, letting water, foliage, and light dissolve hard edges into atmospheric continuity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect

Claude Monet (1903 (begun 1900))

Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect renders London as a <strong>lilac-blue atmosphere</strong> where form yields to light. The bridge’s stone arches persist as anchors, yet the span dissolves into mist while <strong>flecks of lemon and ember</strong> signal modern traffic crossing a city made weightless <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Vertical hints of chimneys haunt the distance, binding industry to beauty as the Thames shimmers with the same notes as the sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Morning on the Seine (series)

Claude Monet (1897)

Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine (series) turns dawn into an inquiry about <strong>perception</strong> and <strong>time</strong>. In this canvas, the left bank’s shadowed foliage dissolves into lavender mist while a pale radiance opens at right, fusing sky and water into a single, reflective field <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

After the Luncheon

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879)

After the Luncheon crystallizes a <strong>suspended instant</strong> of Parisian leisure: coffee finished, glasses dappled with light, and a cigarette just being lit. Renoir’s <strong>shimmering brushwork</strong> and the trellised spring foliage turn the scene into a tapestry of conviviality where time briefly pauses.

The Grand Canal

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s The Grand Canal turns Venice into <strong>pure atmosphere</strong>: the domes of Santa Maria della Salute waver at right while a regiment of <strong>pali</strong> stands at left, their verticals reverberating in the water. The scene asserts <strong>light over architecture</strong>, transforming stone into memory and time into color <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Supper at Emmaus

Caravaggio (1601)

Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus captures the split-second when two disciples recognize Christ in the <strong>breaking of bread</strong>. A raking light isolates Christ’s calm blessing while the disciples erupt—one surging forward with a torn sleeve, the other flinging his arms wide—so the shock of revelation reads as bodily fact. The teetering <strong>basket of fruit</strong> and Eucharistic table amplify themes of abundance and fragility <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

Sunflowers

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is a <strong>yellow-on-yellow</strong> still life that stages a full <strong>cycle of life</strong> in fifteen blooms, from fresh buds to brittle seed heads. The thick impasto, green shocks of stem and bract, and the vase signed <strong>“Vincent”</strong> turn a humble bouquet into an emblem of endurance and fellowship <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Vase of Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1889)

Vase of Flowers is a late‑1880s still life in which Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a humble blue‑green jug and a tumbling bouquet into a <strong>laboratory of color and touch</strong>. Against a warm ocher wall and reddish tabletop, coral and vermilion blossoms flare while cool greens and violets anchor the mass, letting <strong>color function as drawing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The work affirms Renoir’s belief that flower painting was a space for bold experimentation that fed his figure art.

The Skiff (La Yole)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1875)

In The Skiff (La Yole), Pierre-Auguste Renoir stages a moment of modern leisure on a broad, vibrating river, where a slender, <strong>orange skiff</strong> cuts across a field of <strong>cool blues</strong>. Two women ride diagonally through the shimmer; an <strong>oar’s sweep</strong> spins a vortex of color as a sailboat, villa, and distant bridge settle the scene on the Seine’s suburban edge <sup>[1]</sup>. Renoir turns motion and light into a single sensation, using a high‑chroma, complementary palette to fuse human pastime with nature’s flux <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Irises

Vincent van Gogh (1889)

Painted in May 1889 at the Saint-Rémy asylum garden, Vincent van Gogh’s <strong>Irises</strong> turns close observation into an act of repair. Dark contours, a cropped, print-like vantage, and vibrating complements—violet/blue blossoms against <strong>yellow-green</strong> ground—stage a living frieze whose lone <strong>white iris</strong> punctuates the field with arresting clarity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Wheatfield with Crows

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

A panoramic wheatfield splits around a rutted track under a storm-charged sky while black crows rush toward us. Van Gogh drives complementary blues and yellows into collision, fusing <strong>nature’s vitality</strong> with <strong>inner turbulence</strong>.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

Portrait of Dr. Gachet distills Van Gogh’s late ambition for a <strong>modern, psychological portrait</strong> into vibrating color and touch. The sitter’s head sinks into a greenish hand above a <strong>blazing orange-red table</strong>, foxglove sprig nearby, while waves of <strong>cobalt and ultramarine</strong> churn through coat and background. The chromatic clash turns a quiet pose into an <strong>empathic image of fragility and care</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

Claude Monet (1908–1912)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk fuses the Benedictine church’s dark silhouette with a sky flaming from apricot to cobalt, turning architecture into atmosphere. The campanile’s vertical and its wavering reflection anchor a sea of trembling color, staging a meditation on <strong>permanence</strong> and <strong>flux</strong>.

Dance at Bougival

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

In Dance at Bougival, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a crowded suburban dance into a <strong>private vortex of intimacy</strong>. Rose against ultramarine, skin against shade, and a flare of the woman’s <strong>scarlet bonnet</strong> concentrate the scene’s energy into a single turning moment—modern leisure made palpable as <strong>touch, motion, and light</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Beach at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet (1867)

In The Beach at Sainte-Adresse, Claude Monet stages a modern shore where <strong>labor and leisure intersect</strong> under a broad, changeable sky. The bright <strong>blue beached boat</strong> and the flotilla of <strong>rust-brown working sails</strong> punctuate a turquoise channel, while a fashionably dressed pair sits mid-beach, spectators to the traffic of the port. Monet’s brisk, broken strokes make the scene feel <strong>caught between tides and weather</strong>, a momentary balance of work, tourism, and atmosphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Star

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1878)

Edgar Degas’s The Star shows a prima ballerina caught at the crest of a pose, her tutu a <strong>vaporous flare</strong> against a <strong>murky, tilted stage</strong>. Diagonal floorboards rush beneath her single pointe, while pale, ghostlike dancers linger in the wings, turning triumph into a scene of <strong>radiant isolation</strong> <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Charing Cross Bridge

Claude Monet (1901)

In Charing Cross Bridge, Claude Monet turns London into <strong>atmosphere</strong> itself: the bridge flattens into a cool, horizontal band while mauves, lavenders, and pearly grays veil the city. Spirals of <strong>pink steam</strong> and pockets of pale <strong>blue</strong> read as trains, lamps, or smoke transfigured by weather, so place becomes <strong>sensation</strong> rather than structure.

The Dead Toreador

Édouard Manet (probably 1864)

Manet’s The Dead Toreador isolates a matador’s corpse in a stark, horizontal close‑up, replacing the spectacle of the bullring with <strong>silence</strong> and <strong>abrupt finality</strong>. Black costume, white stockings, a pale pink cape, the sword’s hilt, and a small <strong>pool of blood</strong> become the painting’s cool, modern vocabulary of death <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Édouard Manet (1867–1868)

Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian confronts state violence with a <strong>cool, reportorial</strong> style. The wall of gray-uniformed riflemen, the <strong>fragmented canvas</strong>, and the dispassionate loader at right turn the killing into <strong>impersonal machinery</strong> that implicates the viewer <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Sixty Last Suppers

Andy Warhol (1986)

Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers multiplies Leonardo’s scene into a vast grid, turning a singular sacred image into <strong>serial</strong> signage. From afar it reads as an architectural surface; up close, silkscreen <strong>variations</strong>—blurs, darker panels, dropped ink—reassert the human trace <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

Rembrandt van Rijn (1633)

Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee stages a clash of <strong>human panic</strong> and <strong>divine composure</strong> at the instant before the miracle. A torn mainsail whips across a steeply tilted boat as terrified disciples scramble, while a <strong>serenely lit Christ</strong> anchors a pocket of calm—an image of faith holding within chaos <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. It is Rembrandt’s only painted seascape, intensifying its dramatic singularity in his oeuvre <sup>[2]</sup>.

The Ambassadors

Hans Holbein the Younger (1533)

Holbein’s The Ambassadors is a double-portrait staged before a green curtain, where shelves of scientific instruments, books, and musical devices enact <strong>Renaissance learning</strong> while an anamorphic <strong>skull</strong> and a veiled <strong>crucifix</strong> counter it with mortality and salvation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work balances worldly status—fur, velvet, Oriental carpet—with a sober theology of limits amid the <strong>Reformation’s discord</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Doge's Palace

Claude Monet (1908)

Monet’s The Doge’s Palace translates Venice’s emblem of authority into an <strong>atmospheric drama</strong> of lilac, cream, and ultramarine. Architecture becomes a <strong>screen for light</strong>, as the ogival windows and double arcades blur into vibrating strokes mirrored by the lagoon’s <strong>second architecture</strong>—its reflection <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

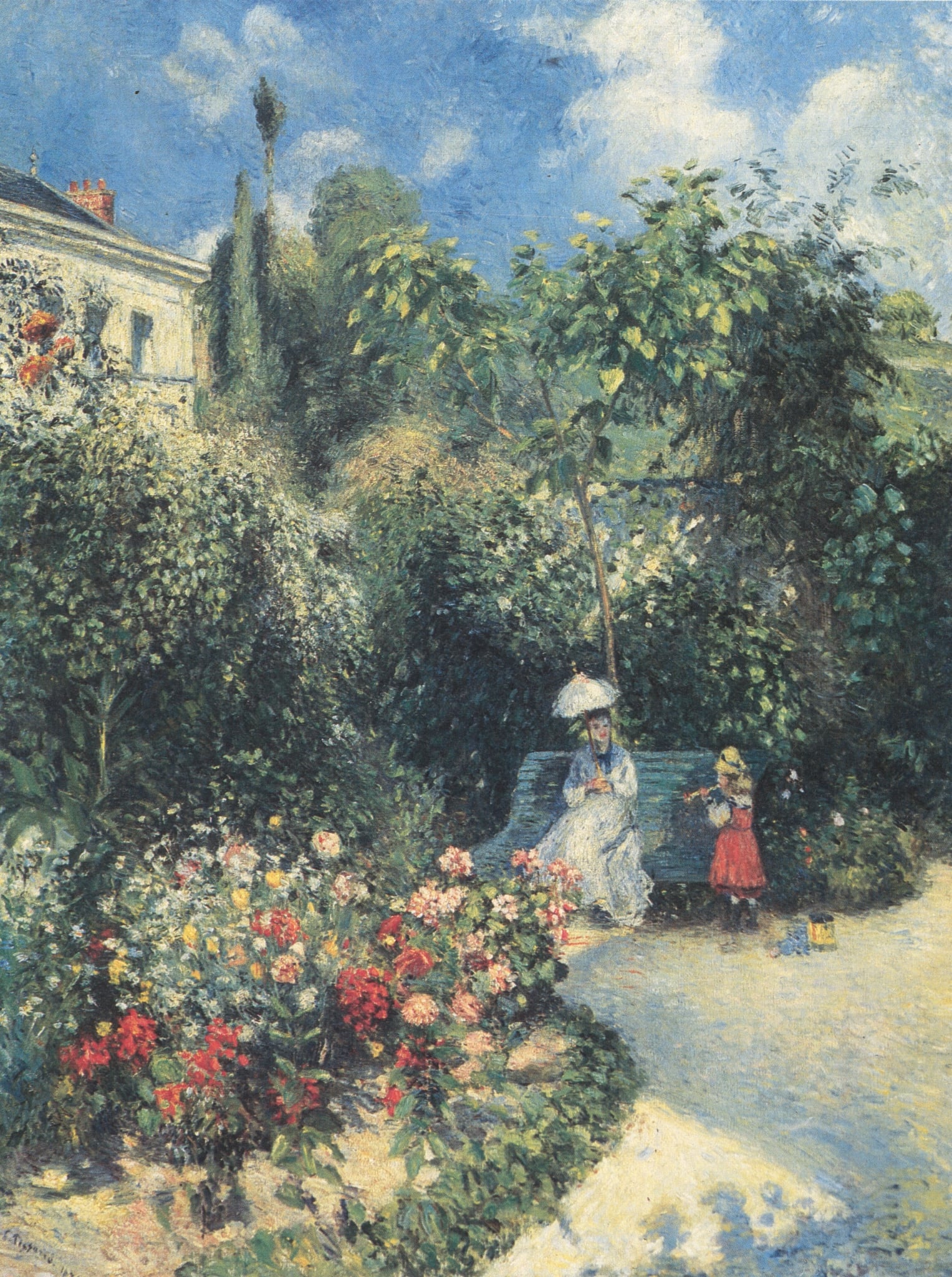

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Flood at Port-Marly

Alfred Sisley (1876)

In Flood at Port-Marly, Alfred Sisley turns a flooded street into a reflective stage where <strong>human order</strong> and <strong>natural flux</strong> converge. The aligned, leafless trees function like measuring rods against the water, while flat-bottomed boats replace carriages at the curb. With cool, silvery strokes and a cloud-laden sky, Sisley asserts that the scene’s true drama is <strong>atmosphere</strong> and <strong>adaptation</strong>, not catastrophe <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne

Alfred Sisley (1872)

Alfred Sisley's The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne crystallizes the encounter between <strong>modern engineering</strong> and <strong>riverside leisure</strong> under <strong>Impressionist light</strong>. The diagonal suspension bridge, dark pylons, and filigreed truss command the left foreground while small boats skim the Seine, their wakes breaking into shimmering strokes that echo the sky.

The Fighting Temeraire

J. M. W. Turner (1839)

In The Fighting Temeraire, J. M. W. Turner sets a <strong>ghostly man‑of‑war</strong> against a <strong>sooty steam tug</strong> under a blazing, emblematic sunset. The pale ship’s towering masts and slack rigging read like memory, while the tug’s black smoke cuts through the rigging where a flag once flew, signaling <strong>power passing from sail to steam</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. A crescent moon and a humble buoy punctuate a river turned to molten gold, marking both ending and beginning <sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Cliff, Etretat

Claude Monet (1882–1883)

<strong>The Cliff, Etretat</strong> stages a confrontation between <strong>permanence and flux</strong>: the dark mass of the arch and needle holds like a monument while ripples of coral, green, and blue light skate across the water. The low <strong>solar disk</strong> fixes the instant, and Monet’s fractured strokes make the sea and sky feel like time itself turning toward dusk. The arch reads as a <strong>threshold</strong>—an opening to the unknown that organizes vision and meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Red Boats, Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Red Boats, Argenteuil crystallizes a luminous afternoon on the Seine, where two <strong>vermilion hulls</strong> anchor a scene of leisure and light. The tremoring <strong>reflections</strong> and vertical <strong>masts/poplars</strong> weave nature and modern recreation into a single atmospheric field <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Rembrandt van Rijn (1632)

Rembrandt van Rijn turns a civic commission into a drama of <strong>knowledge made visible</strong>. A cone of light binds the ruff‑collared surgeons, the pale cadaver, and Dr. Tulp’s forceps as he raises the <strong>forearm tendons</strong> to explain the hand. Book and body face each other across the table, staging the tension—and alliance—between <strong>textual authority</strong> and <strong>empirical observation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

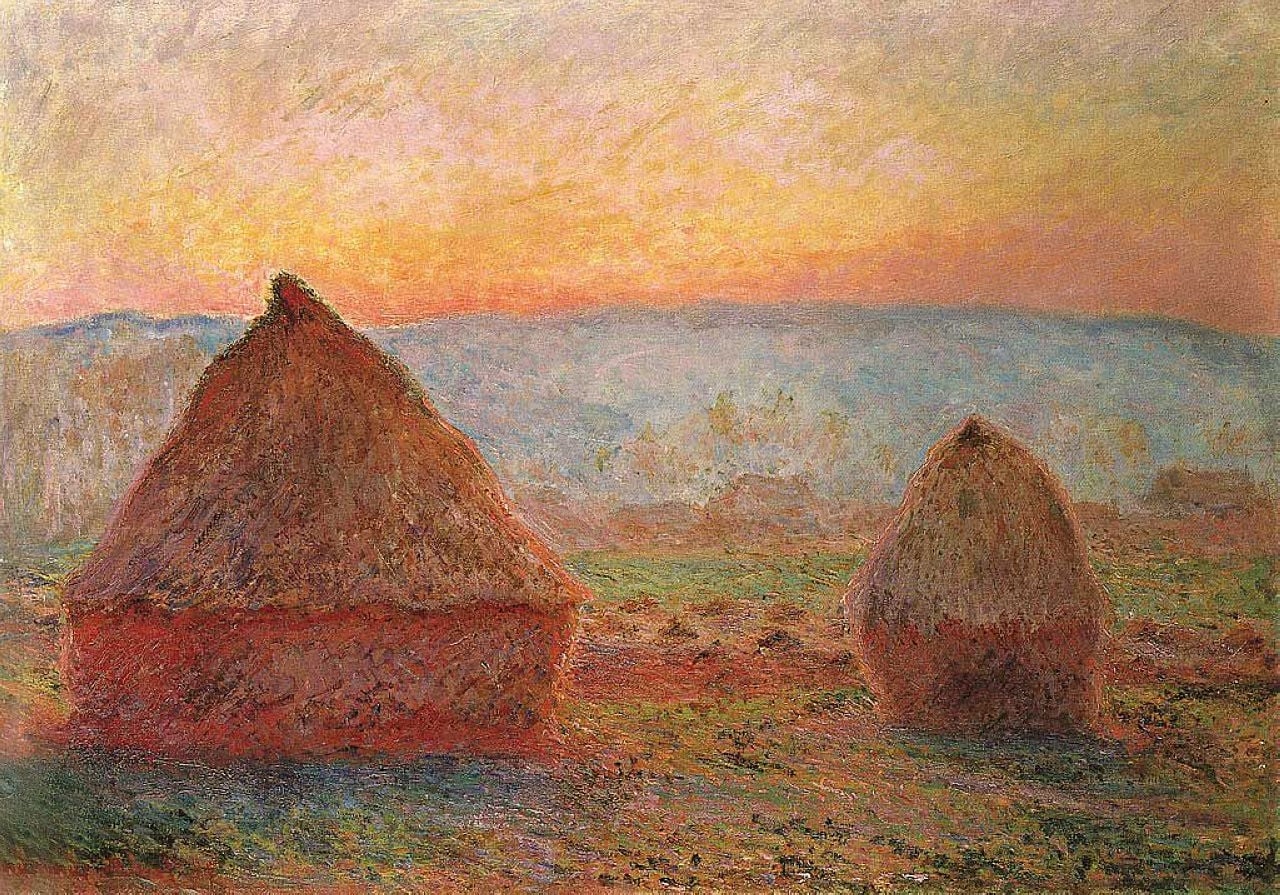

Haystack, Sunset

Claude Monet (1891)

Two conical stacks blaze against a cooling horizon, turning stored grain into a drama of <strong>light, time, and rural wealth</strong>. Monet’s broken strokes fuse warm oranges and cool violets so the stacks seem to glow from within, embodying the <strong>transience</strong> of a single sunset and the <strong>endurance</strong> of agrarian cycles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

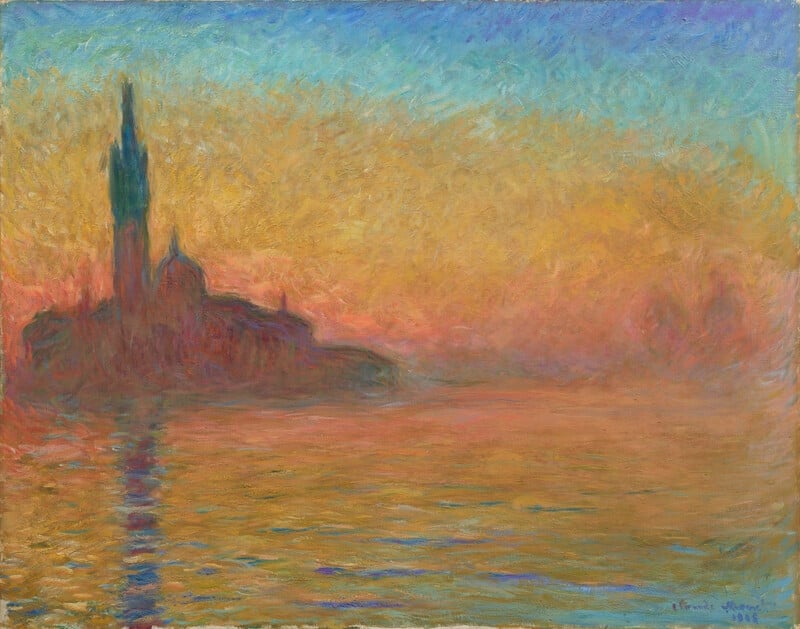

San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight turns Venice into a <strong>luminous threshold</strong> where stone, air, and water merge. The dark, melting silhouette of the church and its vertical reflection anchor a field of <strong>apricot–rose–violet</strong> light that drifts into cool turquoise, making permanence feel provisional <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet’s subject is not the monument, but the <strong>enveloppe</strong> of atmosphere that momentarily creates it <sup>[4]</sup>.

Boulevard des Capucines

Claude Monet (1873–1874)

From a high perch above Paris, Claude Monet turns the Haussmann boulevard into a living current of <strong>light, weather, and motion</strong>. Leafless trees web the view, crowds dissolve into <strong>flickering strokes</strong>, and a sudden <strong>pink cluster of balloons</strong> pierces the cool winter scale <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Girls at the Seashore

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c.1890–1894)

Girls at the Seashore presents two young figures reclining on a grassy bank, their straw hats trimmed with flowers as they look toward a hazy waterway flecked with small sails. Renoir fuses figure and setting through soft, vaporous brushwork so that skin, fabric, foliage, and sea share the same light. The image is an ode to <strong>reverie</strong>, <strong>companionship</strong>, and the <strong>fleeting</strong> warmth of summer.

Still Life with Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers (1885) sets a jubilant bouquet in a pale, crackled vase against softly dissolving wallpaper and a wicker screen. With quick, clear strokes and a centered, oval mass, the painting unites <strong>Impressionist color</strong> with a <strong>classical, post-Italy structure</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The slight droop of blossoms turns the domestic scene into a gentle <strong>vanitas</strong>—a savoring of beauty before it fades <sup>[5]</sup>.

Children on the Seashore, Guernsey

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1883)

Renoir’s Children on the Seashore, Guernsey crystallizes a wind‑bright moment of modern leisure with <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a gently choreographed group of children. The central girl in a white dress and black feathered hat steadies a toddler while a pink‑clad companion leans in and a sailor‑suited boy rests on the pebbles—an intimate triangle set against a <strong>shimmering, populated sea</strong>. The canvas makes light and movement the protagonists, dissolving edges into <strong>pearly surf and sun‑washed cliffs</strong>.

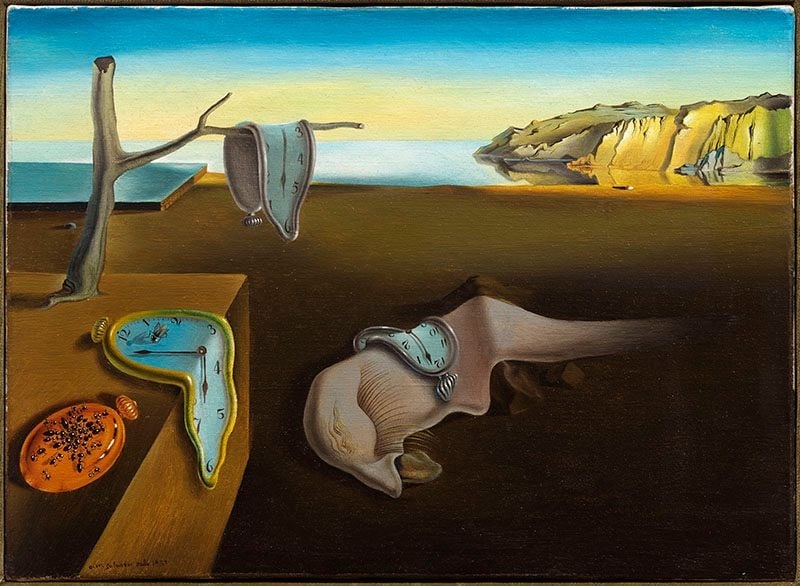

The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dali (1931)

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory turns clock time into <strong>soft, malleable matter</strong>, staging a dream in which chronology buckles and the self dissolves. Four pocket watches droop across a barren platform, a dead branch, and a lash‑eyed biomorph, while ants overrun a hard, closed watch—a sign of <strong>decay</strong> and the futility of mechanical order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Kiss

Gustav Klimt (1908 (completed 1909))

The Kiss stages human love as a <strong>sacred union</strong>, fusing two figures into a single, gold-clad form against a timeless field. Klimt opposes <strong>masculine geometry</strong> (black-and-white rectangles) to <strong>feminine organic rhythm</strong> (spirals, circles, flowers), then resolves them in radiant harmony <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Las Meninas

Diego Velazquez (1656)

In Las Meninas, a luminous Infanta anchors a shadowed studio where the painter pauses at a vast easel and a small wall mirror reflects the monarchs. The scene folds artist, sitters, and viewer into one reflexive tableau, turning court protocol into a meditation on <strong>seeing and being seen</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. A bright doorway at the rear deepens space and time, as if someone has just entered—or is leaving—the picture we occupy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

Hieronymus Bosch (c.1490–1500)

The Garden of Earthly Delights unfolds a three‑act moral narrative—<strong>innocence</strong>, <strong>seduction</strong>, and <strong>retribution</strong>—from Eden to a punitive <strong>Musical Hell</strong>. Bosch binds the scenes through recurring emblems (notably the <strong>owl</strong>) and by echoing Eden’s crystalline fountain in the center’s fragile, candy‑colored architectures, then in Hell’s broken bodies and instruments. The work dazzles with invention while insisting that <strong>sweet, ephemeral pleasures</strong> end in ruin <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck (1434)

In The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck stages a poised encounter between a richly dressed couple whose joined hands, a single burning candle, and a convex mirror transform a domestic interior into a scene of <strong>status and sanctity</strong>. The painting asserts the artist’s own <strong>presence</strong>—"Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434"—as if to validate the moment while showcasing oil painting’s power to make belief tangible through light, texture, and reflection <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Liberty Leading the People

Eugene Delacroix (1830)

<strong>Liberty Leading the People</strong> turns a real street uprising into a modern myth: a bare‑breasted Liberty in a <strong>Phrygian cap</strong> thrusts the <strong>tricolor</strong> forward as Parisians of different classes surge over corpses and rubble. Delacroix binds allegory to eyewitness detail—Notre‑Dame flickers through smoke, a bourgeois in a top hat shoulders a musket, and a pistol‑waving boy keeps pace—so that freedom appears as both idea and action <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. After its 2024 cleaning, sharper blues, whites, and reds re‑ignite the painting’s charged color drama <sup>[4]</sup>.

The Sleeping Gypsy

Henri Rousseau (1897)

Under a cold moon, a traveler sleeps in a striped robe as a lion pauses to sniff, not strike—an image of <strong>danger held in suspension</strong> and <strong>imagination as protection</strong>. Rousseau’s polished surfaces, flattened distance, and toy-like clarity turn the desert into a <strong>dream stage</strong> where art (the mandolin) and life (the water jar) keep silent vigil <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Marilyn Diptych

Andy Warhol (1962)

Marilyn Diptych crystallizes the paradox of fame: <strong>dazzling allure</strong> and <strong>inevitable decay</strong>. Warhol’s 50 repeated silkscreens—color at left, fading grayscale at right—turn a movie-star headshot into a mass-produced <strong>icon</strong> and a memento of mortality <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Lovers

Rene Magritte (1928)

René Magritte’s The Lovers turns a kiss into an emblem of <strong>desire obstructed</strong>: two figures—she in red, he in a dark suit—press together while their heads are swathed in <strong>white cloth</strong>. Within a cool blue‑grey interior bounded by crown molding and a rust-red wall, intimacy becomes an image of <strong>opacity</strong> rather than revelation <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Manneporte near Étretat

Claude Monet (1886)

Monet’s The Manneporte near Étretat turns the colossal sea arch into a <strong>threshold of light</strong>: rock, sea, and air interlock as shifting color rather than fixed form. Dense lilac–ochre strokes make the cliff feel massive yet <strong>dematerialized</strong> by illumination, while the arch’s opening stages a quiet, glimmering horizon <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

Pablo Picasso (1907)

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon hurls five nudes toward the viewer in a shallow, splintered chamber, turning classical beauty into <strong>sharp planes</strong>, <strong>masklike faces</strong>, and <strong>fractured space</strong>. The fruit at the bottom reads as a sensual lure edged with threat, while the women’s direct gazes indict the beholder as participant. This is the shock point of <strong>proto‑Cubism</strong>, where Picasso reengineers how modern painting means and how looking works <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.