The Persistence of Memory

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1931

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 24.1 x 33 cm

- Location

- The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Persistence of Memory

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Historical Context: The Paranoiac‑Critical Method

Source: Smarthistory; MoMA audio guide; Encyclopaedia Britannica

Formal Analysis: Scale, Light, and Suspended Duration

Source: MoMA collection and audio; Smarthistory

Symbolic Reading: A Vanitas for the Machine Age

Source: MoMA audio guide; Encyclopaedia Britannica; Dalí Foundation

Place-Based Interpretation: Catalonia as Oneiric Ground

Source: Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation; Smarthistory

Medium Reflexivity: Mimesis as a Tool of Unreason

Source: MoMA collection; Smarthistory; MoMA audio guide

Explore Specific Elements

Dive deeper into individual scenes and details within The Persistence of Memory.

The Melting Watches

Dalí’s melting watches turn the most rigid tool of modern life into soft, drooping membranes, making the impossible look eerily plausible. Rendered with photographic precision, they visualize a world where mechanical time dissolves into the pliable durations of dream and memory.

The Fetal Face

At the center of The Persistence of Memory lies a pallid, biomorphic head—often read as Dalí’s own sleeping profile—over which a soft watch slumps like skin. This uncanny "fetal face" anchors the painting’s dream-logic, fusing the artist’s inner self with Surrealism’s most famous emblem of liquefied time.

The Ants on the Watch

In the lower-left corner of Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory, a copper-colored pocket watch lies face-down as a tight cluster of 25 shiny black ants overruns its case. This lone “hard” watch resists melting, yet it is actively consumed—an image that turns a precision instrument into carrion and makes time itself feel perishable. The swarm is a compact key to Dalí’s Surrealism: seductive, meticulous, and unsettling all at once.

The Dead Tree

At the painting’s left edge, a leafless olive trunk rises from a geometric block, its brittle branch cradling a melting watch. This stark ‘dead tree’ moors Dalí’s dreamscape in his Mediterranean homeland while transforming a symbol of longevity into a quietly shocking emblem of time’s erosion and memory’s strain.

Related Themes

About Salvador Dali

More by Salvador Dali

The Elephants

Salvador Dali (1948)

In The Elephants, Salvador Dali distills a stark paradox of <strong>weight and weightlessness</strong>: gaunt elephants tiptoe on <strong>stilt-thin legs</strong> while bearing stone <strong>obelisks</strong>. The blazing red-orange sky and tiny human figures compress ambition into a vision of <strong>precarious power</strong> and time stretched thin <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Swans Reflecting Elephants

Salvador Dali (1937)

Swans Reflecting Elephants stages a calm Catalan lagoon where three swans and a thicket of bare trees flip into monumental <strong>elephants</strong> in the mirror of water. Salvador Dali crystallizes his <strong>paranoiac-critical</strong> method: a meticulously painted illusion that makes perception generate its own doubles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work locks grace to gravity, surface to depth, turning the lake into a theater of <strong>metamorphosis</strong>.

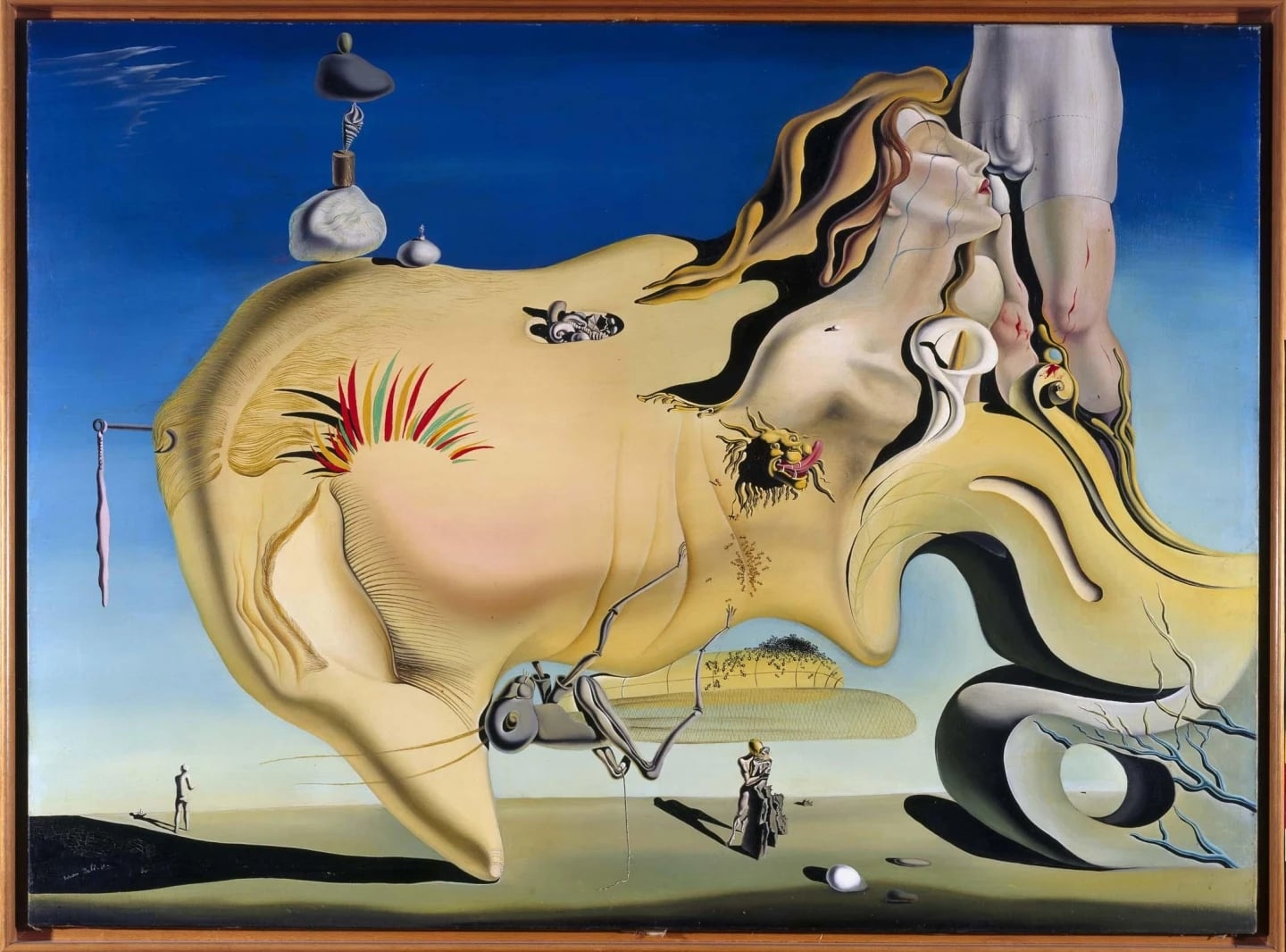

The Great Masturbator

Salvador Dali (1929)

The Great Masturbator condenses Dalí’s newly ignited desire and crippling dread into a single, biomorphic head set against a crystalline Catalan sky. Ants, a gaping grasshopper, a lion’s tongue, a bleeding knee, crutches, stones, and an egg collide to script a confession where <strong>eros</strong> and <strong>decay</strong> are inseparable <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Its precision staging turns autobiography into a <strong>surreal map of compulsion</strong> at the moment Gala enters his life <sup>[1]</sup>.