Landscape & place

Featured Artworks

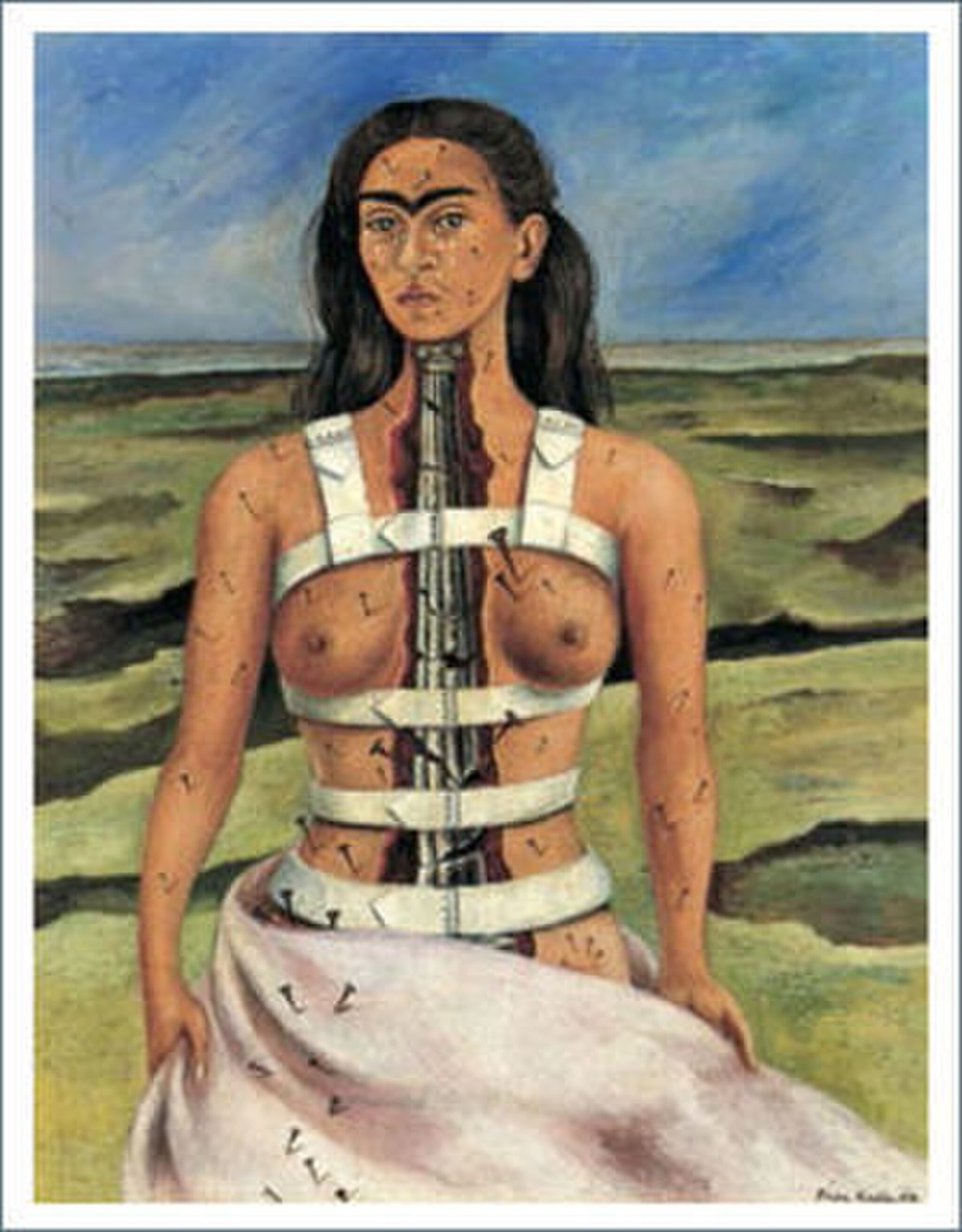

The Broken Column

Frida Kahlo (1944)

The Broken Column presents a frontal self-image split open to expose a shattered classical spine, mapping <strong>chronic pain</strong> across the body with nails while a white <strong>medical corset</strong> both supports and imprisons. Against a cracked, barren landscape, Kahlo’s steady gaze transforms injury into <strong>endurance</strong> and self-possession <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

View of Delft

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1660–1661)

View of Delft turns a faithful city prospect into a meditation on <strong>civic order, resilience, and time</strong>. Beneath a low horizon, drifting clouds cast mobile shadows while shafts of sun ignite blue roofs and the bright spire of the <strong>Nieuwe Kerk</strong>, holding the scene’s moral center <sup>[1]</sup>. Small figures and moored boats ground prosperity in <strong>everyday community</strong> without breaking the hush.

The Sleeping Venus

Giorgione (c. 1508–1510)

In The Sleeping Venus, the goddess reclines across a rolling landscape, her body a serene diagonal that fuses human beauty with nature’s forms. Cool, <strong>silvery drapery</strong> and <strong>deep red cushions</strong> intensify her luminous flesh, while the right-hand <strong>Venus pudica</strong> gesture suspends desire between revelation and restraint. The painting crystallizes the Venetian ideal of poetic harmony (<strong>poesia</strong>) and inaugurates the fully realized reclining nude in Western art <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup><sup>[6]</sup>.

Children Playing on the Beach

Mary Cassatt (1884)

In Children Playing on the Beach, Mary Cassatt brings the viewer down to a child’s eye level, granting everyday play the weight of <strong>serious, self-contained work</strong>. The cool horizon and tiny boats open onto <strong>modern space and possibility</strong>, while the cropped, tilted foreground seals us inside the children’s focused world <sup>[1]</sup>.

Women in the Garden

Claude Monet (1866–1867)

Claude Monet’s Women in the Garden choreographs four figures in a sunlit bower to test how <strong>white dresses</strong> register <strong>dappled light</strong> and shadow. The path, parasol, and clipped flowers frame a modern ritual of leisure while turning fashion into an instrument of <strong>perception</strong>. The scene reads less as portraiture than as a manifesto for painting the <strong>momentary</strong> outdoors <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

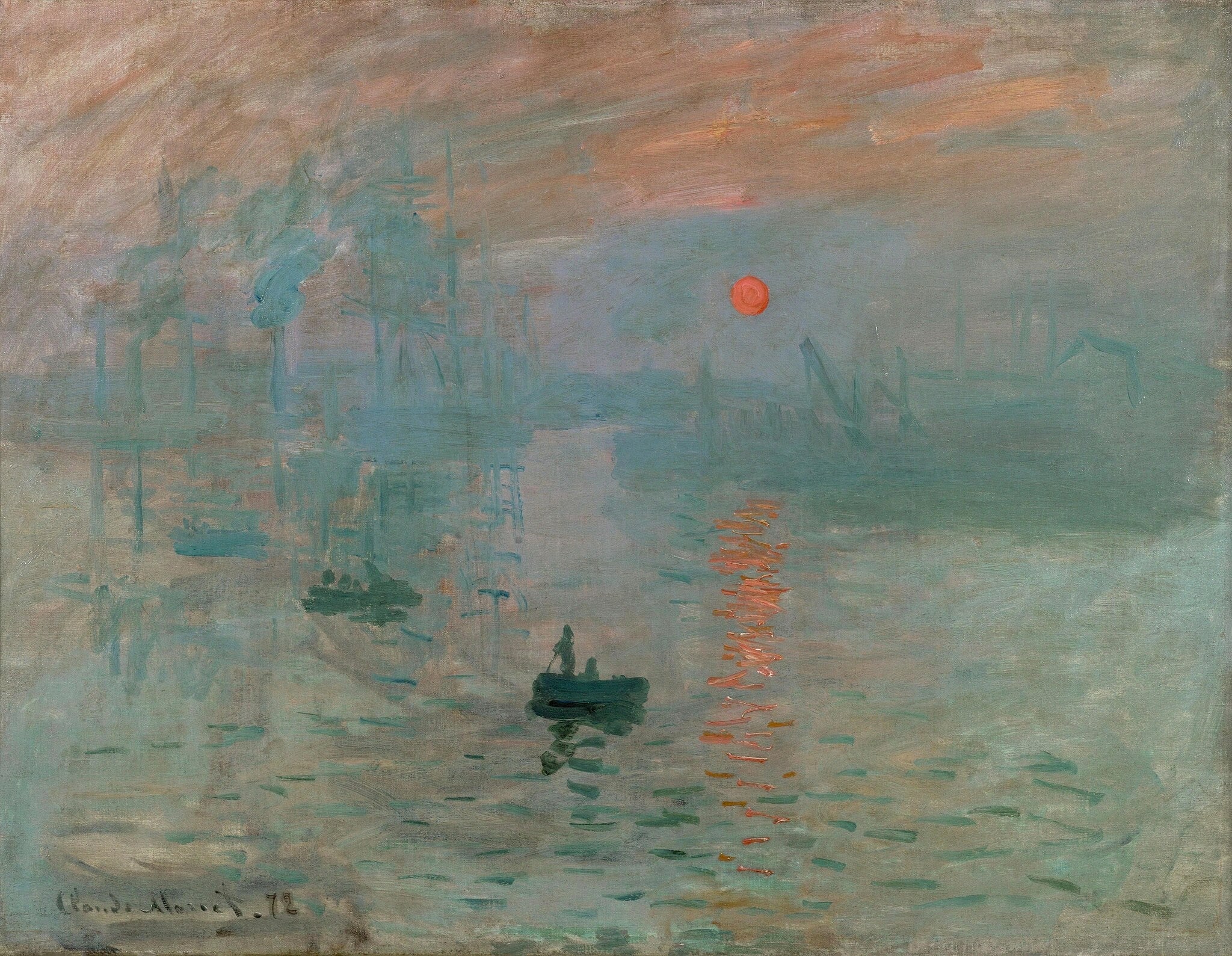

Impression, Sunrise

Claude Monet (1872)

In Impression, Sunrise, Claude Monet turns Le Havre’s fog-bound harbor into an experiment in <strong>immediacy</strong> and <strong>modernity</strong>. Cool blue-greens dissolve cranes, masts, and smoke, while a small skiff cuts the water beneath a blazing, <strong>equiluminant</strong> orange sun whose vertical reflection stitches the scene together <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The effect is a poised dawn where industry meets nature, a quiet <strong>awakening</strong> rendered through light rather than line.

The Artist's Garden at Giverny

Claude Monet (1900)

In The Artist's Garden at Giverny, Claude Monet turns his cultivated Clos Normand into a field of living color, where bands of violet <strong>irises</strong> surge toward a narrow, rose‑colored path. Broken, flickering strokes let greens, purples, and pinks mix optically so that light seems to tremble across the scene, while lilac‑toned tree trunks rhythmically guide the gaze inward <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Water Lilies

Claude Monet (1899)

<strong>Water Lilies</strong> centers on an arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> suspended over a pond where lilies and rippling reflections fuse into a single, vibrating surface. Monet turns the scene into a study of <strong>perception-in-flux</strong>, letting water, foliage, and light dissolve hard edges into atmospheric continuity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Pont Neuf Paris

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1872)

In Pont Neuf Paris, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns the oldest bridge in Paris into a stage where <strong>light</strong> and <strong>movement</strong> bind a city back together. From a high perch, he orchestrates crowds, carriages, gas lamps, the rippling Seine, and a fluttering <strong>tricolor</strong> so that everyday bustle reads as civic grace <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Water Lily Pond

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond transforms a designed garden into a theater of <strong>perception and reflection</strong>. The pale, arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> hovers over a surface where lilies, reeds, and mirrored willow fronds dissolve boundaries between water and sky, proposing <strong>seeing itself</strong> as the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Morning on the Seine (series)

Claude Monet (1897)

Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine (series) turns dawn into an inquiry about <strong>perception</strong> and <strong>time</strong>. In this canvas, the left bank’s shadowed foliage dissolves into lavender mist while a pale radiance opens at right, fusing sky and water into a single, reflective field <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Grand Canal

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s The Grand Canal turns Venice into <strong>pure atmosphere</strong>: the domes of Santa Maria della Salute waver at right while a regiment of <strong>pali</strong> stands at left, their verticals reverberating in the water. The scene asserts <strong>light over architecture</strong>, transforming stone into memory and time into color <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

Caspar David Friedrich (ca. 1817)

A solitary figure stands on a jagged crag above a churning <strong>sea of fog</strong>, his back turned in the classic <strong>Rückenfigur</strong> pose. Caspar David Friedrich transforms the landscape into an inner stage where <strong>awe, uncertainty, and resolve</strong> meet at the edge of perception <sup>[3]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Summer's Day

Berthe Morisot (about 1879)

Two women drift on a boat in the Bois de Boulogne, their dresses, hats, and a bright blue parasol fused with the lake’s flicker by Morisot’s swift, <strong>zig‑zag brushwork</strong>. The scene turns a brief outing into a poised study of <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>female companionship</strong> in public space <sup>[1]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Cliff Walk at Pourville

Claude Monet (1882)

Claude Monet’s The Cliff Walk at Pourville renders wind, light, and sea as interlocking forces through <strong>shimmering, broken brushwork</strong>. Two small walkers—one beneath a pink parasol—stand near the <strong>precipitous cliff edge</strong>, their presence measuring the vastness of turquoise water and bright sky dotted with white sails. The scene fuses leisure and the <strong>modern sublime</strong>, making perception itself the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Wheatfield with Crows

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

A panoramic wheatfield splits around a rutted track under a storm-charged sky while black crows rush toward us. Van Gogh drives complementary blues and yellows into collision, fusing <strong>nature’s vitality</strong> with <strong>inner turbulence</strong>.

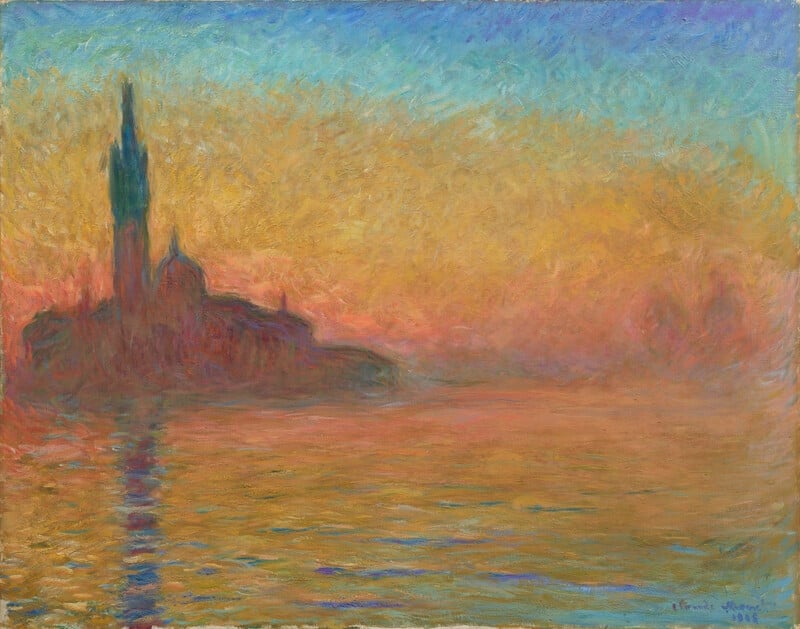

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

Claude Monet (1908–1912)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk fuses the Benedictine church’s dark silhouette with a sky flaming from apricot to cobalt, turning architecture into atmosphere. The campanile’s vertical and its wavering reflection anchor a sea of trembling color, staging a meditation on <strong>permanence</strong> and <strong>flux</strong>.

Regatta at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet (1867)

On a brilliant afternoon at the Normandy coast, a diagonal <strong>pebble beach</strong> funnels spectators with parasols toward a bay scattered with <strong>white-sailed yachts</strong>. Monet’s quick, broken strokes set <strong>wind, water, and light</strong> in synchrony, turning a local regatta into a modern scene of leisure held against the vastness of sea and sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Dance in the City

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance in the City stages an urban waltz where decorum and desire briefly coincide. A couple’s close embrace—his black tailcoat enclosing her luminous white satin gown—creates a <strong>cool, elegant</strong> harmony against potted palms and marble. Renoir’s refined, post‑Impressionist touch turns social ritual into <strong>sensual modernity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Rain, Steam and Speed

J. M. W. Turner (1844)

In Rain, Steam and Speed, J. M. W. Turner fuses weather and industry into a single onrushing vision, as a dark locomotive thrusts along the diagonal of Brunel’s Maidenhead Railway Bridge through veils of rain and light. The blurred fields, river, and town dissolve into a charged atmosphere where <strong>rain</strong>, <strong>steam</strong>, and <strong>speed</strong> become the true subjects. Counter-motifs—a small boat beneath pale arches and a near-invisible hare ahead of the train—stage a drama between pre‑industrial life and modern velocity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Édouard Manet (1867–1868)

Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian confronts state violence with a <strong>cool, reportorial</strong> style. The wall of gray-uniformed riflemen, the <strong>fragmented canvas</strong>, and the dispassionate loader at right turn the killing into <strong>impersonal machinery</strong> that implicates the viewer <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

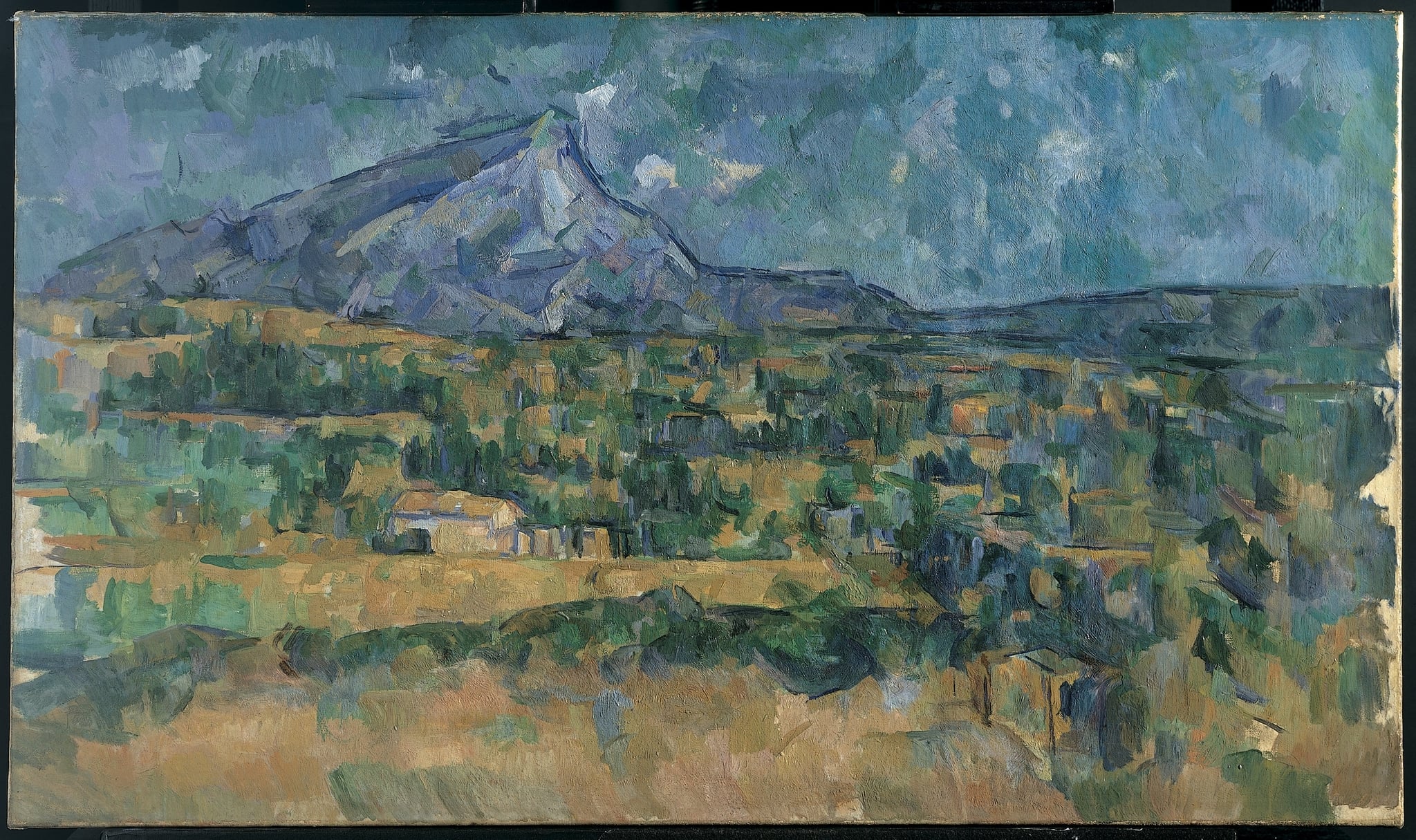

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne (1902–1906)

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire renders the Provençal massif as a constructed order of <strong>planes and color</strong>, not a fleeting impression. Cool blues and violets articulate the mountain’s facets, while <strong>ochres and greens</strong> laminate the fields and blocky houses, binding atmosphere and form into a single structure <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Doge's Palace

Claude Monet (1908)

Monet’s The Doge’s Palace translates Venice’s emblem of authority into an <strong>atmospheric drama</strong> of lilac, cream, and ultramarine. Architecture becomes a <strong>screen for light</strong>, as the ogival windows and double arcades blur into vibrating strokes mirrored by the lagoon’s <strong>second architecture</strong>—its reflection <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Bathers at Asnières

Georges Seurat (1884)

Bathers at Asnières stages a scene of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine, where workers recline and wade beneath a hazy, unified light. Seurat fuses <strong>classicizing stillness</strong> with an <strong>industrial backdrop</strong> of chimneys, bridges, and boats, turning ordinary rest into a monumental, ordered image of urban life <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The canvas balances soft greens and blues with geometric structures, producing a calm yet charged harmony.

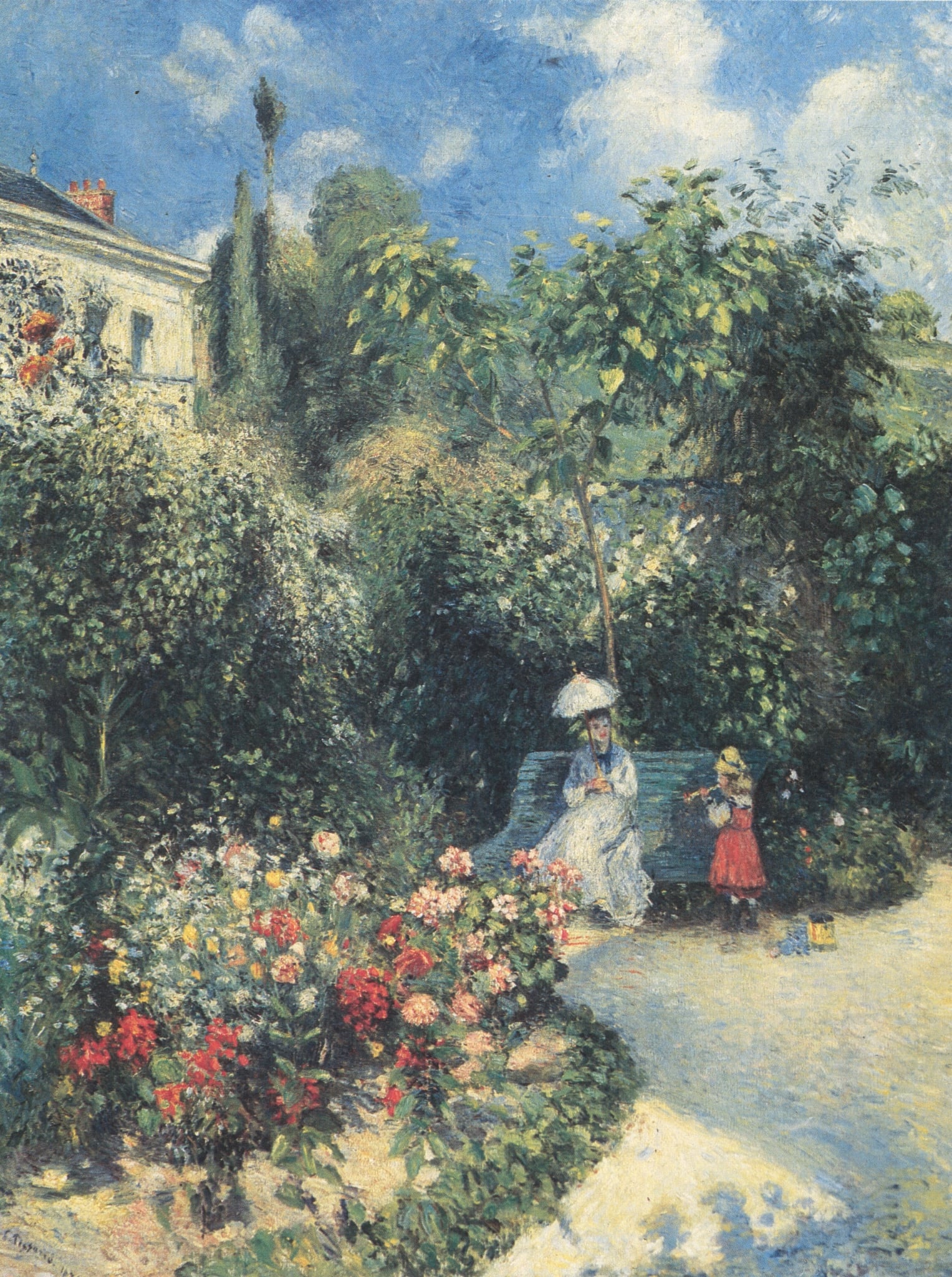

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne

Alfred Sisley (1872)

Alfred Sisley's The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne crystallizes the encounter between <strong>modern engineering</strong> and <strong>riverside leisure</strong> under <strong>Impressionist light</strong>. The diagonal suspension bridge, dark pylons, and filigreed truss command the left foreground while small boats skim the Seine, their wakes breaking into shimmering strokes that echo the sky.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Harbour at Lorient

Berthe Morisot (1869)

Berthe Morisot’s The Harbour at Lorient stages a quiet tension between <strong>private reverie</strong> and <strong>public movement</strong>. A woman under a pale parasol sits on the quay’s stone lip while a flotilla of masted boats idles across a silvery basin, their reflections dissolving into light. Morisot’s <strong>pearly palette</strong> and brisk brushwork make the water read as time itself, holding stillness and departure in the same breath <sup>[1]</sup>.

Reading

Berthe Morisot (1873)

In Berthe Morisot’s <strong>Reading</strong> (1873), a woman in a pale, patterned dress sits on the grass, absorbed in a book while a <strong>green parasol</strong> and <strong>folded fan</strong> lie nearby. Morisot’s quick, luminous brushwork dissolves the landscape into <strong>atmospheric greens</strong> as a distant carriage passes, turning an outdoor scene into a study of interior life. The work makes <strong>female intellectual absorption</strong> its true subject, aligning modern leisure with private thought.

The Cliff, Etretat

Claude Monet (1882–1883)

<strong>The Cliff, Etretat</strong> stages a confrontation between <strong>permanence and flux</strong>: the dark mass of the arch and needle holds like a monument while ripples of coral, green, and blue light skate across the water. The low <strong>solar disk</strong> fixes the instant, and Monet’s fractured strokes make the sea and sky feel like time itself turning toward dusk. The arch reads as a <strong>threshold</strong>—an opening to the unknown that organizes vision and meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Red Boats, Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Red Boats, Argenteuil crystallizes a luminous afternoon on the Seine, where two <strong>vermilion hulls</strong> anchor a scene of leisure and light. The tremoring <strong>reflections</strong> and vertical <strong>masts/poplars</strong> weave nature and modern recreation into a single atmospheric field <sup>[1]</sup>.

Camille Monet on a Garden Bench

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Camille Monet on a Garden Bench (1873) stages an intimate pause where <strong>light, grief, and modern leisure</strong> intersect. Camille, shaded and withdrawn, holds a letter while a <strong>top‑hatted neighbor</strong> hovers; a bright bank of <strong>red geraniums</strong> and a strolling woman with a parasol ignite the distance <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet converts a domestic garden into a scene about <strong>psychological distance</strong> amid fleeting sunlight.

The Japanese Bridge

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Japanese Bridge centers a pale <strong>blue‑green arch</strong> above a horizonless pond, where water‑lily pads and blossoms punctuate a field of shifting reflections. The bridge reads as both structure and <strong>contemplative threshold</strong>, suspending the eye between surface shimmer and mirrored depths <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Poplars on the Epte

Claude Monet (1891)

Claude Monet’s Poplars on the Epte turns a modest river bend into a meditation on <strong>time, light, and perception</strong>. Upright trunks register as steady <strong>vertical chords</strong>, while their broken, shimmering reflections loosen form into <strong>pure sensation</strong>. The image stages a tension between <strong>order and flux</strong> that anchors the series within Impressionism’s core aims <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight turns Venice into a <strong>luminous threshold</strong> where stone, air, and water merge. The dark, melting silhouette of the church and its vertical reflection anchor a field of <strong>apricot–rose–violet</strong> light that drifts into cool turquoise, making permanence feel provisional <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet’s subject is not the monument, but the <strong>enveloppe</strong> of atmosphere that momentarily creates it <sup>[4]</sup>.

The Piazza San Marco, Venice

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1881)

Renoir’s The Piazza San Marco, Venice redefines St. Mark’s Basilica as <strong>atmosphere</strong> rather than architecture, fusing domes, mosaics, and crowd into vibrating color. Blue‑violet shadows sweep the square while pigeons and passersby resolve into <strong>daubs of light</strong>, declaring modern vision as the true subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Seated Bather

Pierre-Auguste Renoir

Renoir’s Seated Bather stages a quiet pause between bathing and reverie, fusing the model’s pearly flesh with the flicker of stream and stone. The white drapery pooled around her hips and the soft, frontal gaze convert a simple toilette into a <strong>modern Arcadia</strong> where body and landscape dissolve into light. In this late-Impressionist idiom, Renoir refines the nude as a <strong>timeless ideal</strong> felt through color and touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

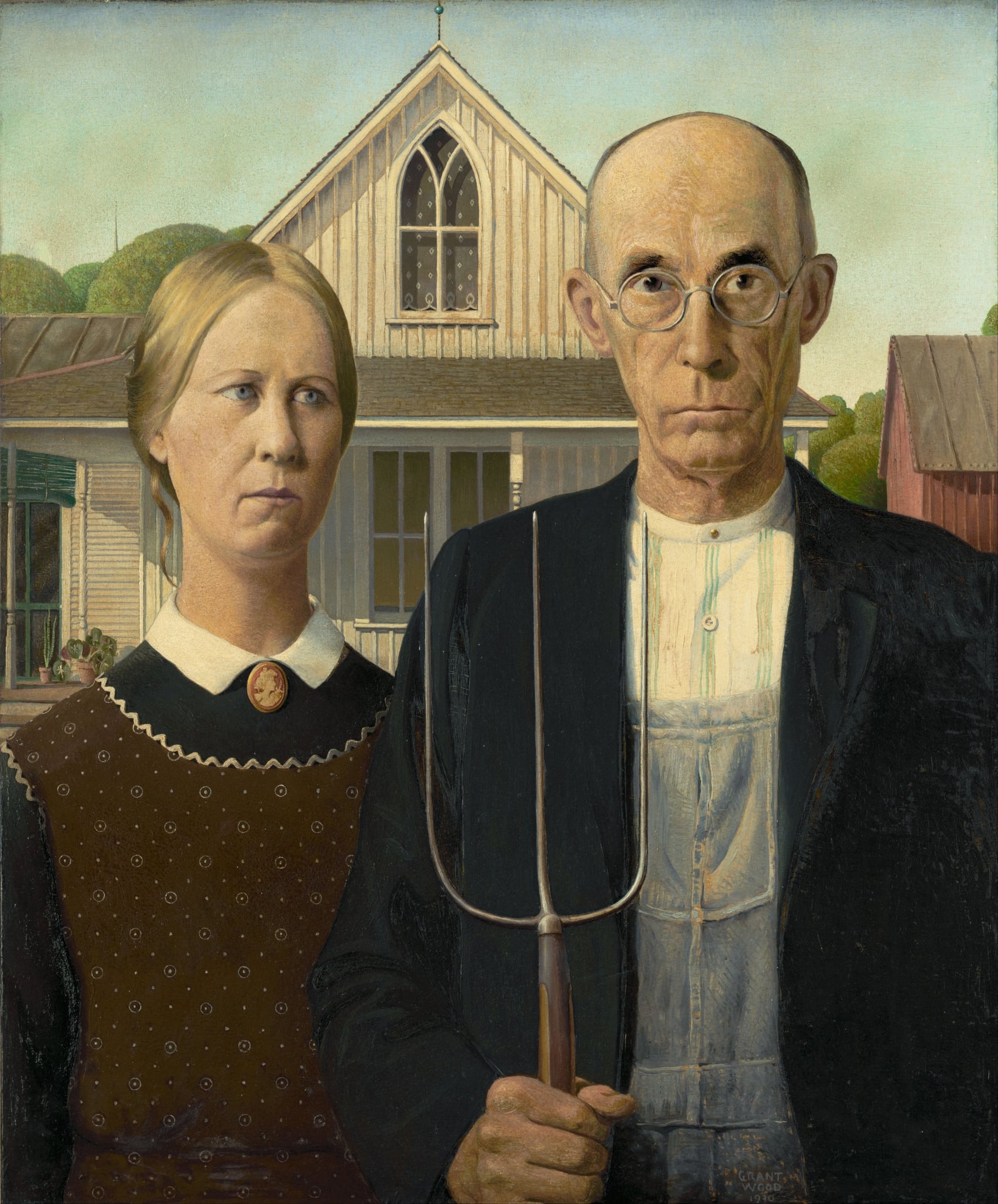

American Gothic

Grant Wood (1930)

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) turns a plain Midwestern homestead into a <strong>moral emblem</strong> by binding two flinty figures to the strict geometry of a Carpenter Gothic gable and a three‑tined pitchfork. The painting’s cool precision and echoing verticals create a <strong>compressed ethic of work, order, and restraint</strong> that can read as both tribute and critique <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Children on the Seashore, Guernsey

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1883)

Renoir’s Children on the Seashore, Guernsey crystallizes a wind‑bright moment of modern leisure with <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a gently choreographed group of children. The central girl in a white dress and black feathered hat steadies a toddler while a pink‑clad companion leans in and a sailor‑suited boy rests on the pebbles—an intimate triangle set against a <strong>shimmering, populated sea</strong>. The canvas makes light and movement the protagonists, dissolving edges into <strong>pearly surf and sun‑washed cliffs</strong>.

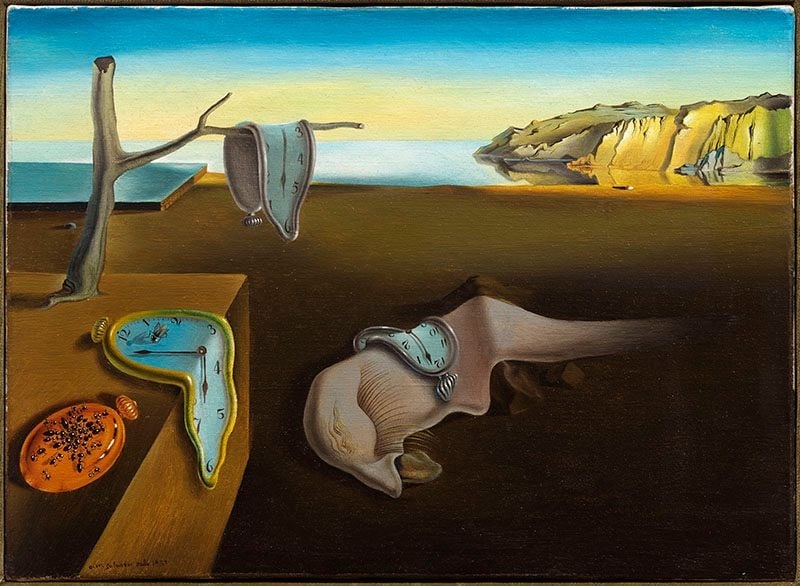

The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dali (1931)

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory turns clock time into <strong>soft, malleable matter</strong>, staging a dream in which chronology buckles and the self dissolves. Four pocket watches droop across a barren platform, a dead branch, and a lash‑eyed biomorph, while ants overrun a hard, closed watch—a sign of <strong>decay</strong> and the futility of mechanical order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Kiss

Gustav Klimt (1908 (completed 1909))

The Kiss stages human love as a <strong>sacred union</strong>, fusing two figures into a single, gold-clad form against a timeless field. Klimt opposes <strong>masculine geometry</strong> (black-and-white rectangles) to <strong>feminine organic rhythm</strong> (spirals, circles, flowers), then resolves them in radiant harmony <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Hokusai (ca. 1830–32)

The Great Wave off Kanagawa distills a universal drama: fragile laboring boats face a <strong>towering breaker</strong> while <strong>Mount Fuji</strong> sits small yet immovable. Hokusai wields <strong>Prussian blue</strong> to sculpt depth and cold inevitability, fusing ukiyo‑e elegance with Western perspective to stage nature’s power against human resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Son of Man

Rene Magritte (1964)

Rene Magritte’s The Son of Man stages a crisp <strong>everyman</strong> in bowler hat and overcoat before a sea horizon while a <strong>green apple</strong> hovers to block his face. The tiny glimpse of one eye above the fruit turns a straightforward portrait into a <strong>riddle about seeing and knowing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Hay Wain

John Constable (1821)

Set beside Willy Lott’s cottage on the River Stour, The Hay Wain stages a moment of <strong>unhurried rural labor</strong>: an empty timber cart, drawn by three horses with red-collared tack, pauses mid‑ford as weather shifts above. Constable fuses <strong>empirical observation</strong>—rippling reflections, chimney smoke, flickers of white on leaves—with a composed vista of fields opening to sun. The result is a serene yet alert meditation on <strong>work, weather, and continuity</strong> in the English countryside <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

Caspar David Friedrich (ca. 1817)

Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog distills the Romantic encounter with nature into a single <strong>Rückenfigur</strong> poised on jagged rock above a rolling <strong>sea of mist</strong>. The cool, receding vista and the figure’s still stance convert landscape into an <strong>inner drama of contemplation</strong> and the <strong>sublime</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Elephants

Salvador Dali (1948)

In The Elephants, Salvador Dali distills a stark paradox of <strong>weight and weightlessness</strong>: gaunt elephants tiptoe on <strong>stilt-thin legs</strong> while bearing stone <strong>obelisks</strong>. The blazing red-orange sky and tiny human figures compress ambition into a vision of <strong>precarious power</strong> and time stretched thin <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Swans Reflecting Elephants

Salvador Dali (1937)

Swans Reflecting Elephants stages a calm Catalan lagoon where three swans and a thicket of bare trees flip into monumental <strong>elephants</strong> in the mirror of water. Salvador Dali crystallizes his <strong>paranoiac-critical</strong> method: a meticulously painted illusion that makes perception generate its own doubles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work locks grace to gravity, surface to depth, turning the lake into a theater of <strong>metamorphosis</strong>.

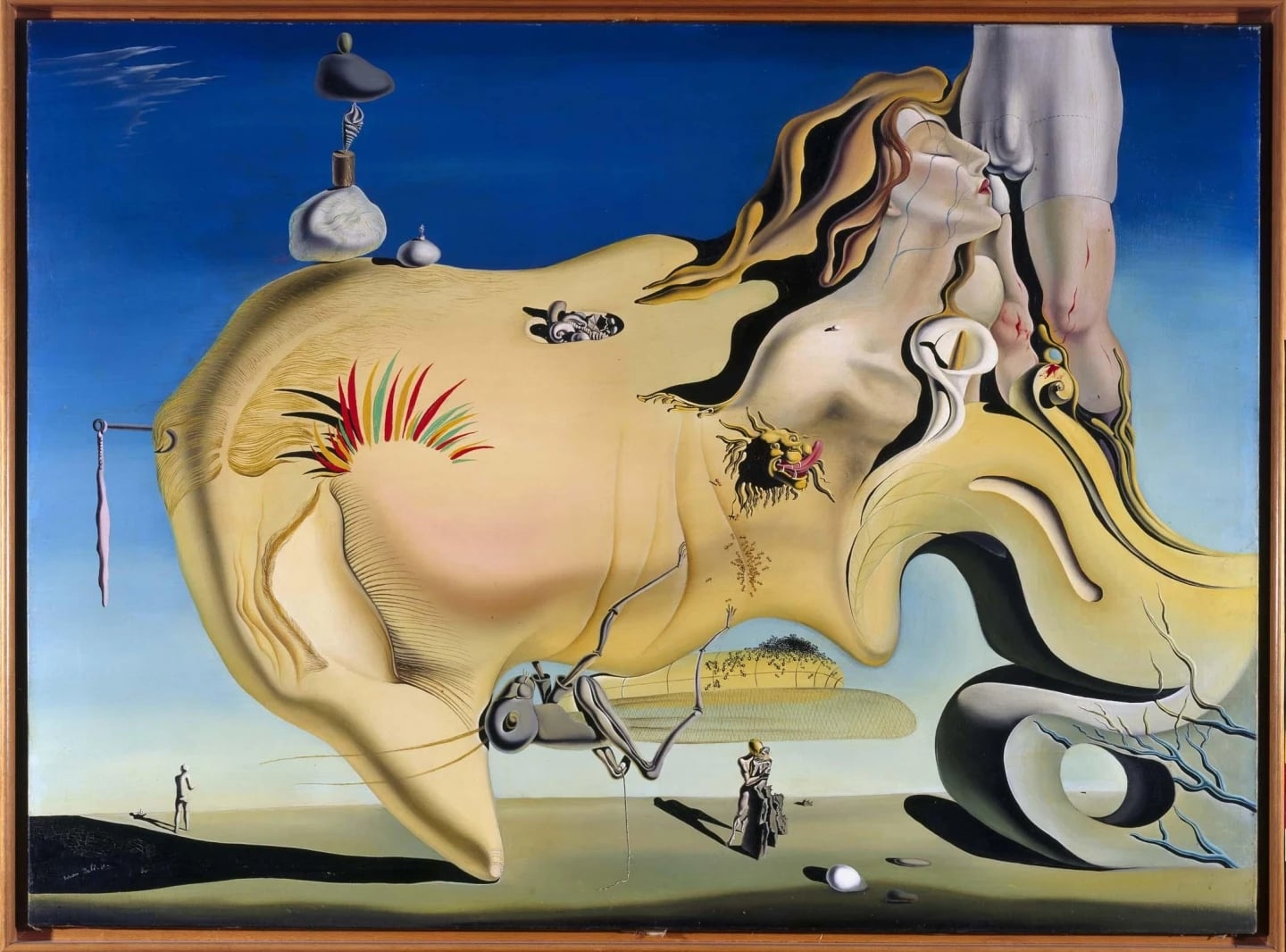

The Great Masturbator

Salvador Dali (1929)

The Great Masturbator condenses Dalí’s newly ignited desire and crippling dread into a single, biomorphic head set against a crystalline Catalan sky. Ants, a gaping grasshopper, a lion’s tongue, a bleeding knee, crutches, stones, and an egg collide to script a confession where <strong>eros</strong> and <strong>decay</strong> are inseparable <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Its precision staging turns autobiography into a <strong>surreal map of compulsion</strong> at the moment Gala enters his life <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Manneporte near Étretat

Claude Monet (1886)

Monet’s The Manneporte near Étretat turns the colossal sea arch into a <strong>threshold of light</strong>: rock, sea, and air interlock as shifting color rather than fixed form. Dense lilac–ochre strokes make the cliff feel massive yet <strong>dematerialized</strong> by illumination, while the arch’s opening stages a quiet, glimmering horizon <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.