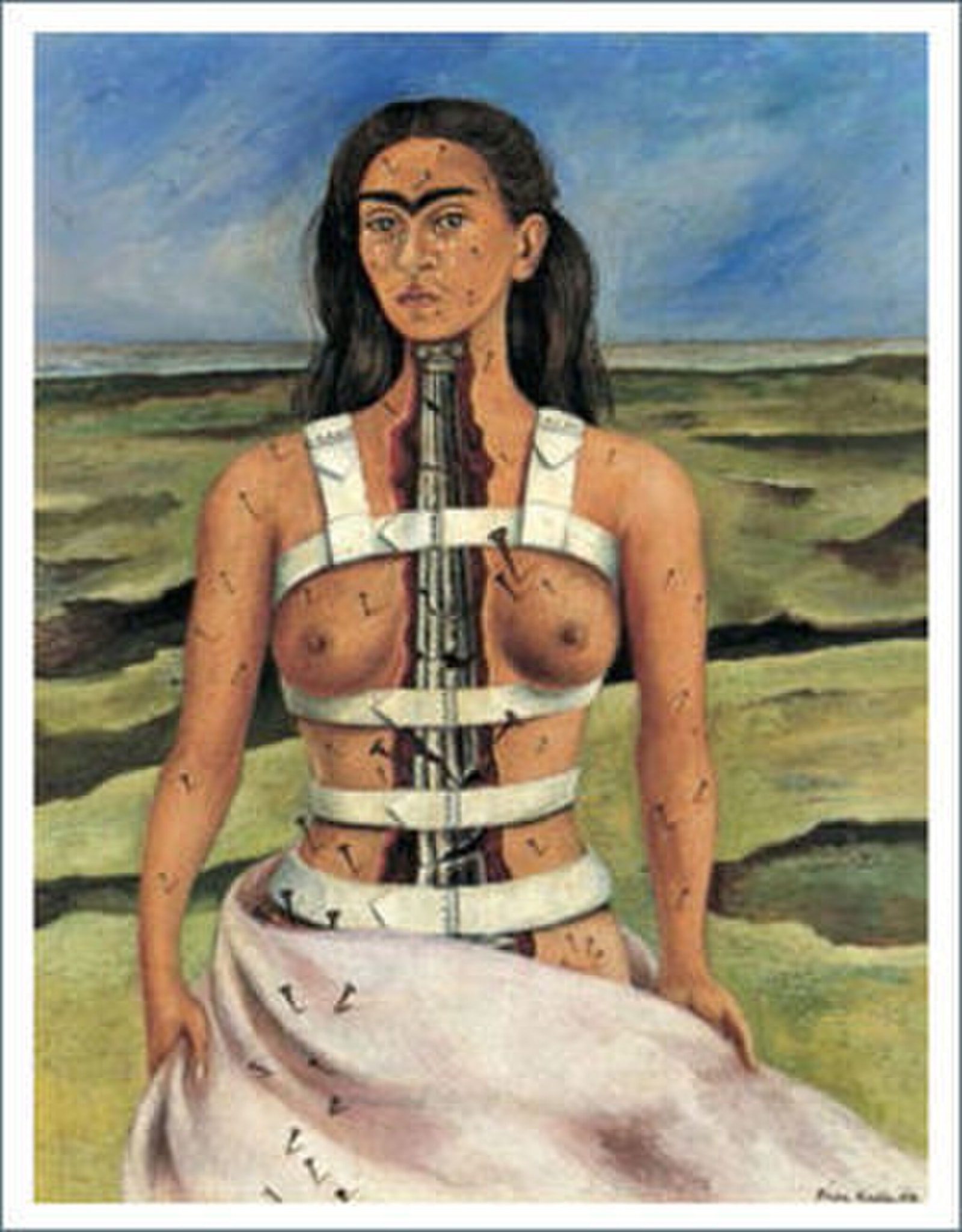

The Broken Column

by Frida Kahlo

The Broken Column presents a frontal self-image split open to expose a shattered classical spine, mapping chronic pain across the body with nails while a white medical corset both supports and imprisons. Against a cracked, barren landscape, Kahlo’s steady gaze transforms injury into endurance and self-possession [1][2].

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1944

- Medium

- Oil on masonite

- Dimensions

- 39.8 × 30.6 cm

- Location

- Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

The work stages a confrontation between the viewer’s desire to diagnose and the subject’s refusal to be reduced to a case. Kahlo opens her torso along a vertical fissure to reveal an Ionic column—the emblem of classical order—fractured and splinted from throat to pelvis; masonry replaces anatomy to equate structural stability with bodily integrity, then denies both by cracking it apart 14. Blood rims the split like seismographic red lines, while the surrounding ground is literally fissured, turning private injury into geology; pain reverberates from body to world 14. Dozens of small nails stipple her skin. Rather than dramatizing a single wound, the nails map systemic, distributed pain, the felt reality of neuropathic or post-surgical suffering that medicine often tabulates but does not picture 2. Their density over the torso and leg turns skin into a grid of sensation, an atlas whose points are all active. Yet the head is steady, shoulders squared, and eyes meet ours directly—composure as a chosen posture, not an absence of feeling. This disjunction is the painting’s argument: lucidity and agony can be simultaneous, and vision (hers and ours) must accommodate both 5.

The white corset cinching her ribs and abdomen literalizes the double bind of treatment: it holds her together even as it immobilizes and marks her as a patient 13. The straps bite into the flesh; support is indistinguishable from restraint. Kahlo had been prescribed rigid braces during and after the spinal surgeries of 1944, and the painting channels that lived apparatus into iconography 34. The pale drapery at her hips and the puncturing nails evoke Passion imagery—arrows of Saint Sebastian, the loincloth of Christ—yet there is no external savior, no staging of redemption 47. By appropriating the language of martyrdom while fixing the gaze squarely on the viewer, she reclaims the spectacle of suffering as authorship. The tears coursing down her cheeks align her with weeping devotional figures in Mexican visual culture, but their smallness and her unwavering stare turn pathos into dignity, signaling a self that chooses to be seen and to make meaning of what is seen 16.

Why The Broken Column is important is that it invents a visual grammar for chronic pain and for the ethics of looking at it. The painting refuses both sentimentality and abstraction: its nails are specific, countable, yet deliberately innumerable; its corset is mechanical, documented, and metaphorical at once 23. By substituting architecture for anatomy, Kahlo argues that disability is not a private defect but a reconfiguration of structure, with social and environmental echoes—hence the riven earth behind her 15. And by meeting our gaze, she converts the clinic’s observational power into reciprocal recognition. The result is an image that has shaped medical humanities discourse, feminist self-representation, and modern art’s capacity to articulate embodied experience without relinquishing agency 256.

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Broken Column

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

💬 Ask questions about this artwork!

Interpretations

Medical Humanities: Cartographies of Chronic Pain

The nails function as a distributed sensorium, turning skin into a map where every point is active; this anticipates medical-humanities efforts to visualize pain beyond a 1–10 scale. Scholars note Kahlo’s precision—nails are discrete, countable yet effectively innumerable—producing a paradox of data and excess that mirrors chronic pain’s clinical elusiveness 2. Read against her real orthopedic devices, the image documents therapy while critiquing its inadequacy: the brace supports and immobilizes at once, dramatizing care as constraint 3. In this light the painting is less confession than methodology—a patient-generated diagram of neuropathic experience that supplements what charts and case notes omit, and an ethics-of-looking lesson that binds viewerly recognition to the acknowledgment of ongoing, non-heroic pain 23.

Source: Oxford Academic (Physical Therapy); The Guardian (V&A corsets)

Formal Analysis: Architecture as Anatomy, Masonite as Device

Kahlo’s substitution of a shattered Ionic column for the spine fuses figurative mimesis with allegorical structure; the body becomes a load-bearing system in failure, an architectural section rendered frontal and iconic 7. Painted in oil on masonite, a rigid support used for its smooth, unyielding surface, the work’s materiality echoes the orthopedic steel that held her torso—flatness that reads as brace-like immobilization 1. The shallow, fissured ground and horizon compress space so the figure becomes both monument and fault line, a tectonic cross-section of flesh and earth 17. Tears are minute, almost enamel-like points against an impassive mask, countering theatricality with micro-gesture. The result is a taut dialectic: descriptive exactitude (straps, buckles) against emblematic clarity (column), a structure that makes pain legible without dissolving into symbol alone 17.

Source: Annenberg Learner; Wikipedia (cross-checked)

Devotional Imagery Reframed: Secular Martyrdom without Redemption

The punctures recall the arrows of Saint Sebastian, and the white drapery echoes Christ’s loincloth, yet Kahlo withholds saintly intercession, fixing the viewer with a steady, juridical gaze 7. Within Mexican visual culture, tears often code for intercessory pathos; here their smallness plus her frontal address recast lament as dignity rather than supplication 6. This is a strategic repurposing of sacred iconography: the panel reads as an altarpiece to embodied modernity, where endurance replaces salvation and the witness (the viewer) inherits ethical responsibility. By secularizing Passion motifs, Kahlo estranges familiar devotional affects and redirects them toward the politics of clinical seeing—compelling us to recognize pain without extracting cathartic absolution 467.

Source: Antiques and the Arts (devotional codes); Obelisk Art History; Wikipedia

Post/Anti-Colonial Classicism: Breaking the Canon

Installing a fractured classical column inside a Mexican body, Kahlo stages the failure of imported aesthetic canons to stabilize lived experience. The Ionic order—index of European harmony—appears splinted and useless, a modern allegory of colonial form under stress 5. This aligns with Kahlo’s broader self-fashioning against Surrealist and European expectations, asserting a local, testimonial modernism that refuses exoticization while appropriating Western signs to her own ends 58. Rather than reject classicism outright, she breaks it open and makes its fragments carry the load of biography and disability, an inversion that critiques who gets to define order, beauty, and wholeness in modern art.

Source: The Guardian (2005, politics/surrealism); The Art Story

Disability Studies & the Ethics of Looking

Kahlo’s direct gaze converts the clinic’s one-way observational authority into reciprocity: as we assess, we are assessed. Disability appears not as private defect but as a reconfiguration of structure—architecture replacing anatomy—projected into a fissured environment that insists on social context 27. The work thereby proposes a protocol of viewing: count the nails, note the brace, but do not collapse the subject into a case. In disability-studies terms, she visualizes the social model alongside the medical, embedding impairment within systems (devices, landscapes, viewers) and demanding recognition rather than cure as the ground of encounter 28. The painting thus functions as a theory of spectatorship: to see well is to hold pain and agency together without hierarchy.

Source: Oxford Academic (Physical Therapy); The Art Story

Related Themes

About Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) was a Mexican painter whose work fuses autobiographical trauma, national identity, and meticulous symbolism. After a devastating 1925 accident and years of surgeries, she developed a medicalized visual language that others linked to Surrealism, a label she resisted. Her marriage and 1939 divorce from Diego Rivera mark the biographical crucible in which this painting was made [3][1].

View all works by Frida Kahlo →