Gender & sexuality

Featured Artworks

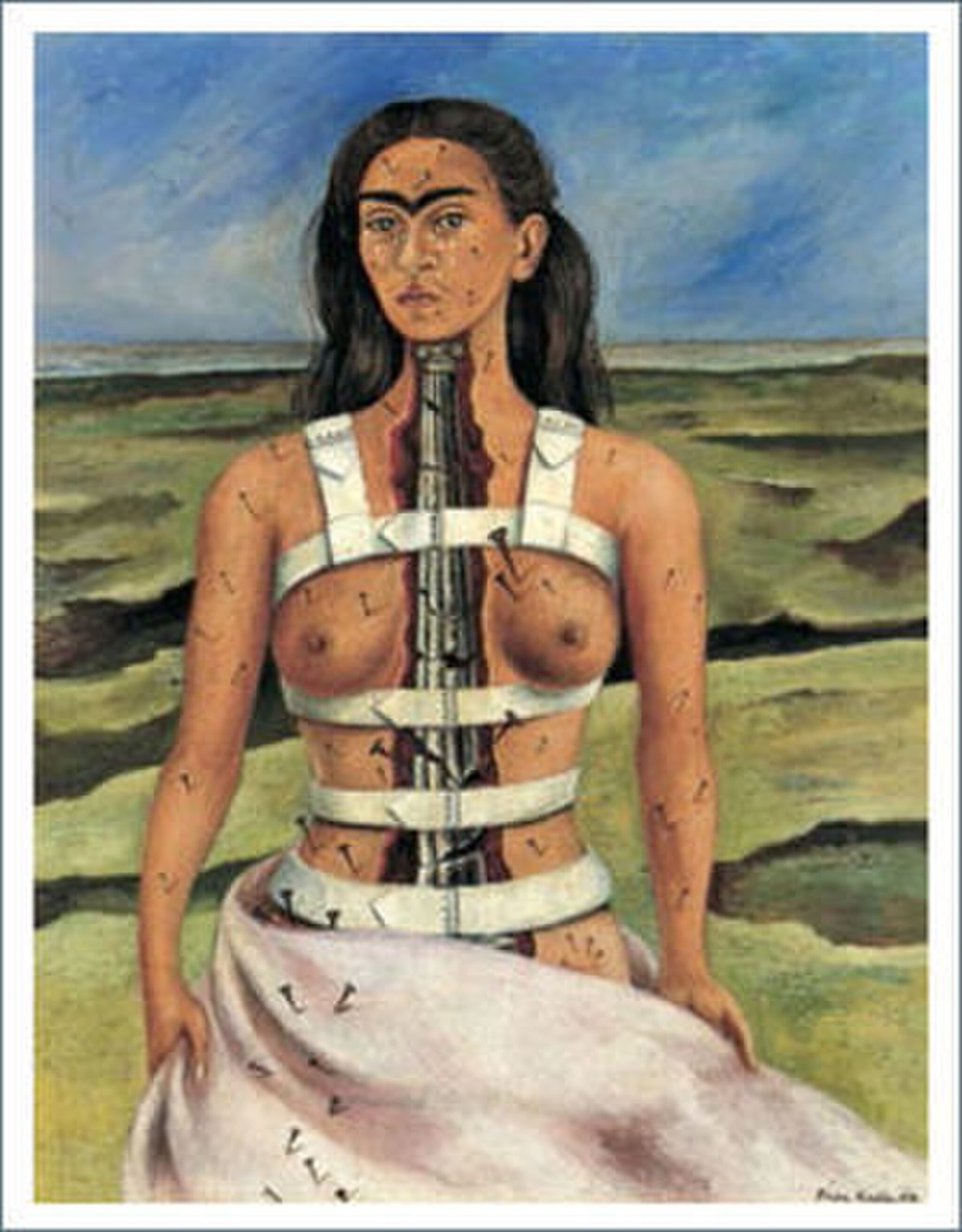

The Broken Column

Frida Kahlo (1944)

The Broken Column presents a frontal self-image split open to expose a shattered classical spine, mapping <strong>chronic pain</strong> across the body with nails while a white <strong>medical corset</strong> both supports and imprisons. Against a cracked, barren landscape, Kahlo’s steady gaze transforms injury into <strong>endurance</strong> and self-possession <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman in Black at the Opera

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman in Black at the Opera stages a taut drama of vision and visibility. A woman in <strong>black attire</strong> raises <strong>opera glasses</strong> while a distant man aims his own at her, setting off a chain of looks that makes public leisure a site of <strong>power, agency, and surveillance</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume)

Claude Monet (1876)

Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume) (1876) stages a witty confrontation between <strong>Parisian modernity</strong> and the fashion for <strong>Japonisme</strong>. A fair-skinned model in a blazing red uchikake preens before a wall tiled with uchiwa fans, lifting a <strong>tricolor</strong> hand fan that asserts Frenchness amid the imported decor. The painting turns costume, props, and gaze into a performance about <strong>desire, display, and identity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Gustav Klimt (1907)

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I stages its sitter as a <strong>secular icon</strong>—a living presence suspended in a field of gold that converts space into <strong>pattern and power</strong>. The naturalistic face and hands emerge from a reliquary-like cascade of eyes, triangles, and tesserae, turning light, ornament, and status into the painting’s true subjects <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

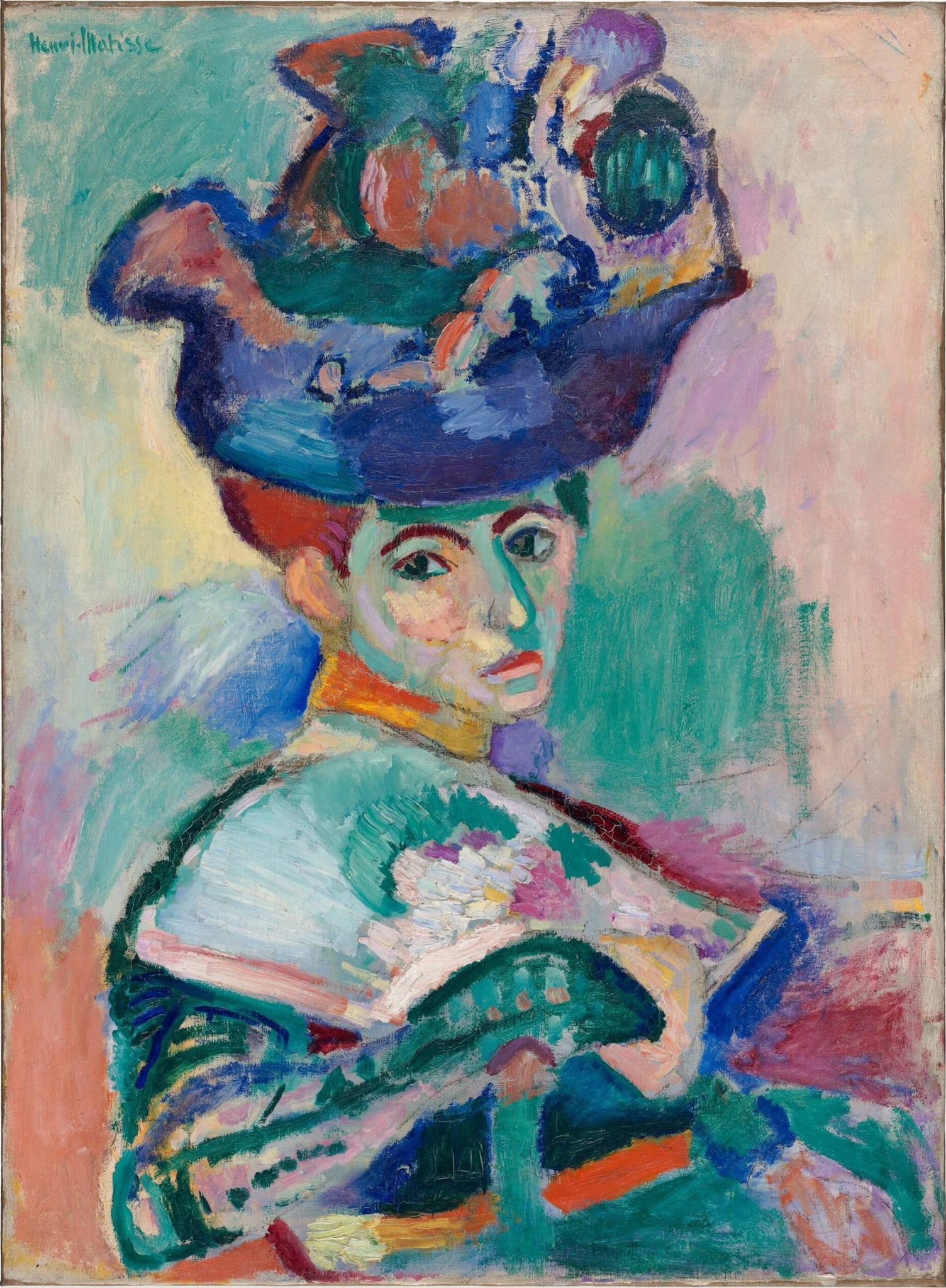

Woman with a Hat

Henri Matisse (1905)

In Woman with a Hat, Henri Matisse turns portraiture into a laboratory for <strong>pure color</strong> and <strong>modern identity</strong>. Jagged greens and violets carve the face; the hat detonates into a crown of brushstrokes; a fan slices the torso into bright planes. The result declares Fauvism’s credo: <strong>feeling over description</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Tea

Mary Cassatt (about 1880)

Mary Cassatt’s The Tea stages a poised, interior <strong>drama of manners</strong>: two women sit close yet feel apart, one thoughtful, the other raising a cup that <strong>veils her face</strong>. A gleaming, oversized <strong>silver tea service</strong> commands the foreground, its reflections turning ritual objects into actors in the scene <sup>[1]</sup>. The shallow, cropped room—striped wall, gilt mirror, marble mantel—compresses the atmosphere into <strong>intimacy edged by restraint</strong>.

Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore

Mary Cassatt (c. 1886)

Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore distills childhood into a quiet drama of <strong>interiority</strong> and <strong>constraint</strong>. The oversized straw hat and plain pinafore bracket a flushed face, downcast eyes, and <strong>clasped hands</strong>, turning a simple pose into a study of modern self‑consciousness <sup>[1]</sup>. Cassatt’s cool grays and swift, luminous strokes make mood—not costume—the subject.

Judith Slaying Holofernes

Artemisia Gentileschi (c. 1612–13)

Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes hurls us into the fatal instant when Judith and her maid overpower the Assyrian general. In a void of darkness, a hard light chisels out straining arms, a heavy sword, and blood darkening the white sheets—an image of <strong>justice enacted through female collaboration</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Embroiderer

Johannes Vermeer (1669–1670)

In The Embroiderer, Johannes Vermeer condenses a world of work into a palm‑sized drama of <strong>attention</strong> and <strong>transformation</strong>. A young woman bends over a lace pillow as loose red and white threads spill in front, while a nascent pattern gathers under her poised fingers. Vermeer’s right‑hand light isolates the act of making and turns domestic labor into <strong>virtuous concentration</strong> <sup>[1]</sup>.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

Caravaggio (1599)

Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes stages the biblical execution as a shocking present-tense event, lit by a raking beam that cuts figures from darkness. The <strong>red curtain</strong> frames a moral spectacle in which <strong>virtue overthrows tyranny</strong>, as Judith’s cool determination meets Holofernes’ convulsed resistance. Radical <strong>naturalism</strong>—from tendon strain to ribboning blood—makes deliverance feel material and irreversible.

Venus of Urbino

Titian (1538)

Titian’s Venus of Urbino turns the mythic goddess into an ideal bride, merging frank <strong>eroticism</strong> with the codes of <strong>marital fidelity</strong>. In a Venetian bedroom, the nude’s direct gaze, roses, sleeping lapdog, and attendants at a cassone bind desire to domestic virtue and fertility <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

A Woman and a Girl Driving

Mary Cassatt (1881)

Cassatt stages a modern scene of <strong>female control</strong> in motion: a woman grips the reins and whip while a girl beside her mirrors the pose, and a groom seated behind looks away. The cropped horse and diagonal harness thrust the carriage forward, placing viewers inside a public outing in the Bois de Boulogne—an arena where visibility signaled status and autonomy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Eight Elvises

Andy Warhol (1963)

A sweeping frieze of eight overlapping, gun‑drawn cowboys marches across a silver field, their forms slipping and ghosting as if frames of a film. Warhol converts a singular star into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>, where <strong>mechanical misregistration</strong> and life‑size scale turn bravado into spectacle <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Bacchus

Caravaggio (c. 1598)

Caravaggio’s Bacchus stages a human-scaled god who offers wine with disarming immediacy, yoking <strong>sensual invitation</strong> to <strong>vanitas</strong> warning. The tilted goblet, blemished fruit, and wilting leaves insist that abundance and youth are <strong>precarious</strong>. A private Roman milieu under Cardinal del Monte shaped this refined, provocative image <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Young Girls at the Piano

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892)

Renoir’s Young Girls at the Piano turns a quiet lesson into a scene of <strong>attunement</strong> and <strong>bourgeois grace</strong>. Two adolescents—one seated at the keys, the other leaning to guide the score—embody harmony between discipline and delight, rendered in Renoir’s late, <strong>luminous</strong> touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David (1784 (exhibited 1785))

In The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David crystallizes <strong>civic duty over private feeling</strong>: three Roman brothers extend their arms to swear allegiance as their father raises <strong>three swords</strong> at the perspectival center. The painting’s severe geometry, austere architecture, and polarized groups of <strong>rectilinear men</strong> and <strong>curving mourners</strong> stage a manifesto of <strong>Neoclassical virtue</strong> and republican resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Girl Arranging Her Hair

Mary Cassatt (1886)

Mary Cassatt’s Girl Arranging Her Hair crystallizes a private rite of <strong>self‑regard</strong> into modern painting. Cool, broken strokes of the pale chemise meet the warm, patterned wall and bamboo furniture, staging a quiet drama of <strong>autonomy</strong> rather than display <sup>[1]</sup>. Exhibited in 1886, the work reframes the toilette as lived experience within Impressionism’s language of immediacy <sup>[2]</sup>.

The Tub

Edgar Degas (1886)

In The Tub (1886), Edgar Degas turns a routine bath into a study of <strong>modern solitude</strong> and <strong>embodied labor</strong>. From a steep, overhead angle, a woman kneels within a circular basin, one hand braced on the rim while the other gathers her hair; to the right, a tabletop packs a ewer, copper pot, comb/brush, and cloth. Degas’s layered pastel binds skin, water, and objects into a single, breathing field of <strong>warm flesh tones</strong> and blue‑greys, collapsing distance between body and still life <sup>[1]</sup>.

Reading Le Figaro

Mary Cassatt (c. 1878–83)

Mary Cassatt’s Reading Le Figaro turns a quiet parlor into a scene of <strong>intellect</strong> and <strong>modern life</strong>. The inverted masthead, mirrored repetition of the paper, and the sitter’s spectacles make <strong>attention</strong>—not appearance—the true subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Through brisk whites and grays, Cassatt dignifies everyday thought as a modern pictorial theme aligned with <strong>Impressionism</strong> <sup>[2]</sup>.

Turquoise Marilyn

Andy Warhol (1964)

In Turquoise Marilyn, Andy Warhol converts a movie star’s face into a <strong>modern icon</strong>: a tightly cropped head floating in a flat <strong>turquoise</strong> field, its <strong>acidic yellow hair</strong>, turquoise eye shadow, and <strong>lipstick-red</strong> mouth stamped by silkscreen’s mechanical bite. The slight <strong>misregistration</strong> around eyes and hair produces a halo-like tremor, fusing <strong>glamour and ghostliness</strong> to expose celebrity as a manufactured surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Summertime

Mary Cassatt (1894)

Mary Cassatt’s Summertime (1894) stages a quiet drama of <strong>attentive looking</strong>: a woman and a girl lean from a cropped boat toward two ducks as the lake flickers with broken color. Cassatt fuses <strong>Impressionism</strong> and <strong>Japonisme</strong>—no horizon, tipped perspective, and abrupt cropping—to press our gaze downward into light-spattered water. The result is an image of <strong>modern leisure</strong> that is also a study of perception itself <sup>[1]</sup>.

Four Marlons

Andy Warhol (1966)

Four Marlons is a 1966 silkscreen by Andy Warhol that multiplies a single biker film-still into a tight 2×2 grid on raw linen. Its inky blacks against a tan, unprimed ground turn the glare of the headlamp, the angled handlebars, and the figure’s guarded pose into a <strong>repeatable icon</strong> of outlaw cool. Warhol’s seriality both <strong>amplifies and drains</strong> the image’s aura, exposing fame as a commodity pattern <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

The Loge

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Loge (1874) turns an opera box into a <strong>stage of looking</strong>, where a woman meets our gaze while her companion scans the crowd through binoculars. The painting’s <strong>frame-within-a-frame</strong> and glittering fashion make modern Parisian leisure both alluring and self-conscious, turning spectators into spectacles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman Reading

Édouard Manet (1880–82)

Manet’s Woman Reading distills a fleeting act into an emblem of <strong>modern self-possession</strong>: a bundled figure raises a journal-on-a-stick, her luminous profile set against a brisk mosaic of greens and reds. With quick, loaded strokes and a deliberately cropped <strong>beer glass</strong> and paper, Manet turns perception itself into subject—asserting the drama of a private mind within a public café world <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Summer's Day

Berthe Morisot (about 1879)

Two women drift on a boat in the Bois de Boulogne, their dresses, hats, and a bright blue parasol fused with the lake’s flicker by Morisot’s swift, <strong>zig‑zag brushwork</strong>. The scene turns a brief outing into a poised study of <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>female companionship</strong> in public space <sup>[1]</sup>.

Jeanne (Spring)

Édouard Manet (1881)

Édouard Manet’s Jeanne (Spring) fuses a time-honored allegory with <strong>modern Parisian fashion</strong>: a crisp profile beneath a cream parasol, set against <strong>luminous, leafy greens</strong>. Manet turns couture—hat, glove, parasol—into the language of <strong>renewal and youth</strong>, making spring feel both perennial and up-to-the-minute <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Child's Bath

Mary Cassatt (1893)

Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (1893) recasts an ordinary ritual as <strong>modern devotion</strong>. From a steep, print-like vantage, interlocking stripes, circles, and diagonals focus attention on <strong>touch, care, and renewal</strong>, turning domestic labor into a subject of high art <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The work synthesizes Impressionist sensitivity with <strong>Japonisme</strong> design to monumentalize the private sphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Floor Scrapers

Gustave Caillebotte (1875)

Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers stages three shirtless workers planing a parquet floor as shafts of light pour through an ornate balcony door. The painting fuses <strong>rigorous perspective</strong> with <strong>modern urban labor</strong>, turning curls of wood and raking light into a ledger of time and effort <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. Its cool, gilded interior makes visible how bourgeois elegance is built on bodily work.

Woman at Her Toilette

Berthe Morisot (1875–1880)

Woman at Her Toilette stages a private ritual of self-fashioning, not a spectacle of vanity. A woman, seen from behind, lifts her arm to adjust her hair as a <strong>black velvet choker</strong> punctuates Morisot’s silvery-violet haze; the <strong>mirror’s blurred reflection</strong> with powders, jars, and a white flower refuses a clear face. Morisot’s <strong>feathery facture</strong> turns a fleeting toilette into modern subjectivity made visible <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Dance at Bougival

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

In Dance at Bougival, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a crowded suburban dance into a <strong>private vortex of intimacy</strong>. Rose against ultramarine, skin against shade, and a flare of the woman’s <strong>scarlet bonnet</strong> concentrate the scene’s energy into a single turning moment—modern leisure made palpable as <strong>touch, motion, and light</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress)

Claude Monet (1866)

Monet’s Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress) turns a full-length portrait into a study of <strong>modern spectacle</strong>. The spotlit emerald-and-black skirt, set against a near-black curtain, makes <strong>fashion</strong> the engine of meaning and the vehicle of status.

Dance in the City

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance in the City stages an urban waltz where decorum and desire briefly coincide. A couple’s close embrace—his black tailcoat enclosing her luminous white satin gown—creates a <strong>cool, elegant</strong> harmony against potted palms and marble. Renoir’s refined, post‑Impressionist touch turns social ritual into <strong>sensual modernity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Jeanne Samary

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1877)

Renoir’s Portrait of Jeanne Samary (1877) turns a modern actress into a study of <strong>radiance and immediacy</strong>, fusing figure and air with shimmering strokes. Cool blue‑green dress notes spark against a warm <strong>coral-pink atmosphere</strong>, while the cheek‑in‑hand pose crystallizes a moment of intimate poise <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Millinery Shop

Edgar Degas (1879–1886)

Edgar Degas’s The Millinery Shop stages modern Paris through a quiet act of <strong>work</strong> rather than display. A young woman, cropped in profile, studies a glowing <strong>orange hat</strong> while faceless stands crowned with ribbons and plumes press toward the picture plane. Degas turns a boutique into a meditation on <strong>labor, commodities, and identity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

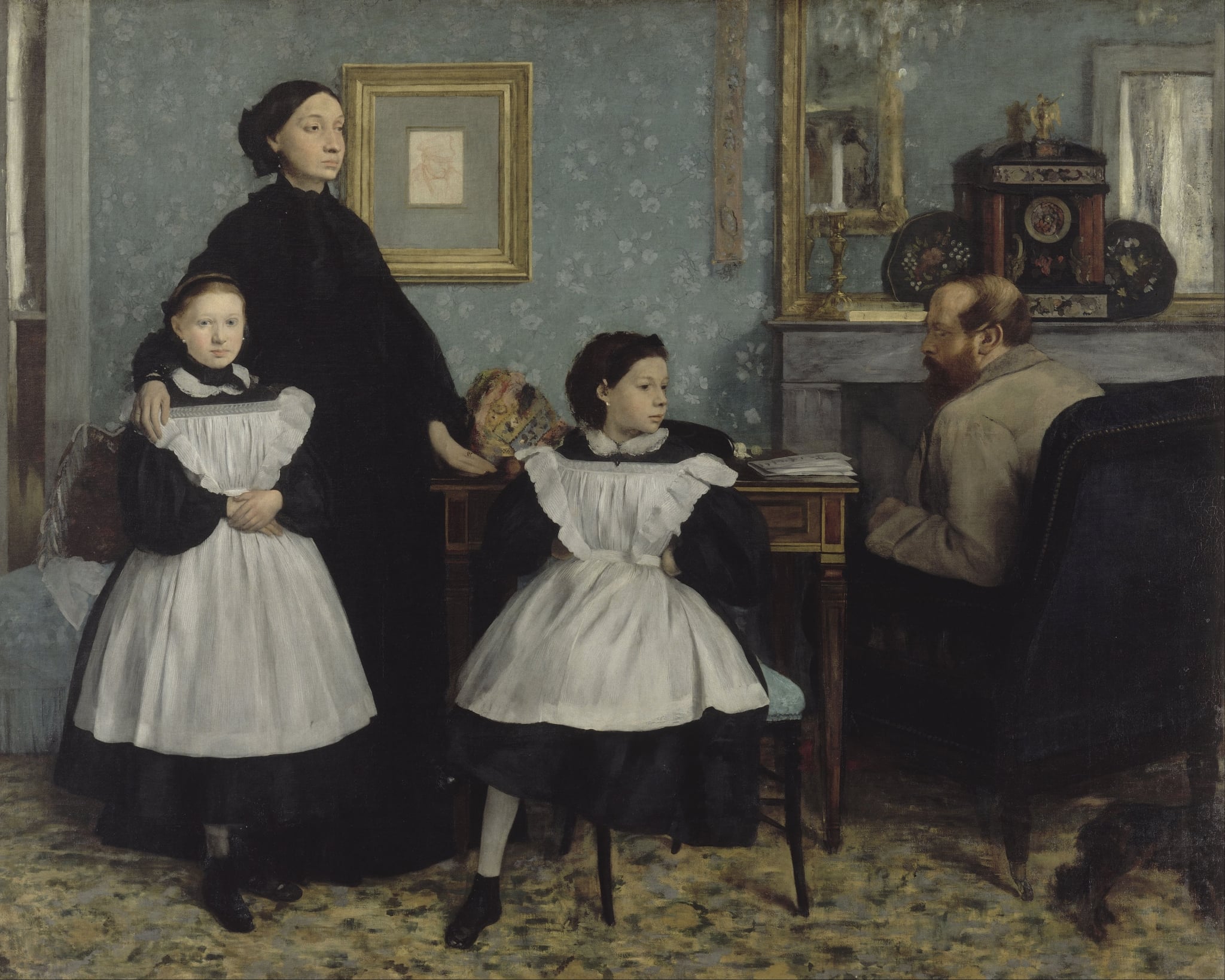

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

Combing the Hair

Edgar Degas (c.1896)

Edgar Degas’s Combing the Hair crystallizes a private ritual into a scene of <strong>compressed intimacy</strong> and <strong>classed labor</strong>. The incandescent field of red fuses figure and room, turning the hair into a <strong>binding ribbon</strong> between attendant and sitter <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Umbrellas

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1881–86)

A sudden shower turns a Paris street into a lattice of <strong>slate‑blue umbrellas</strong>, knitting strangers into a single moving frieze. A bareheaded young woman with a <strong>bandbox</strong> strides forward while a bourgeois mother and children cluster at right, their <strong>hoop</strong> echoing the umbrellas’ arcs <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair

Paul Cézanne (about 1877)

Paul Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (about 1877) turns a domestic sit into a study of <strong>color-built structure</strong> and <strong>compressed space</strong>. Cool blue-greens of dress and skin lock against the saturated <strong>crimson armchair</strong>, converting likeness into an inquiry about how painting makes stability visible <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Jane Avril

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (c. 1891–1892)

In Jane Avril, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec crystallizes a public persona from a few <strong>urgent, chromatic strokes</strong>: violet and blue lines whirl into a cloak, while green and indigo dashes crown a buoyant hat. Her face—sharply keyed in <strong>lemon yellow, lilac, and carmine</strong>—hovers between mask and likeness, projecting poise edged with fatigue. The raw brown ground lets her <strong>whiplash silhouette</strong> materialize like smoke from Montmartre’s nightlife.

The Cup of Tea

Mary Cassatt (ca. 1880–81)

Mary Cassatt’s The Cup of Tea distills a moment of bourgeois leisure into a study of <strong>poise</strong>, <strong>etiquette</strong>, and <strong>private reflection</strong>. A woman in a rose‑pink dress and bonnet, white‑gloved, balances a gold‑rimmed cup against the shimmer of <strong>Impressionist</strong> brushwork, while a green planter of pale blossoms echoes her pastel palette <sup>[1]</sup>. The work turns an ordinary ritual into a modern emblem of women’s experience.

The Harbour at Lorient

Berthe Morisot (1869)

Berthe Morisot’s The Harbour at Lorient stages a quiet tension between <strong>private reverie</strong> and <strong>public movement</strong>. A woman under a pale parasol sits on the quay’s stone lip while a flotilla of masted boats idles across a silvery basin, their reflections dissolving into light. Morisot’s <strong>pearly palette</strong> and brisk brushwork make the water read as time itself, holding stillness and departure in the same breath <sup>[1]</sup>.

Reading

Berthe Morisot (1873)

In Berthe Morisot’s <strong>Reading</strong> (1873), a woman in a pale, patterned dress sits on the grass, absorbed in a book while a <strong>green parasol</strong> and <strong>folded fan</strong> lie nearby. Morisot’s quick, luminous brushwork dissolves the landscape into <strong>atmospheric greens</strong> as a distant carriage passes, turning an outdoor scene into a study of interior life. The work makes <strong>female intellectual absorption</strong> its true subject, aligning modern leisure with private thought.

In the Loge

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s In the Loge (1878) stages modern spectatorship as a drama of <strong>mutual looking</strong>. A woman in dark dress leans forward with <strong>opera glasses</strong>, her <strong>fan closed</strong> on her lap, as a man in the distance raises his own glasses toward her—turning the theater into a circuit of gazes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge

Mary Cassatt (1879)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879) stages modern <strong>spectatorship</strong> inside a plush opera box, where a young woman in pink satin, pearls, and gloves occupies the red velvet seat while a mirror multiplies the chandeliers and balconies. Cassatt fuses <strong>intimacy</strong> and <strong>public display</strong>, using luminous brushwork to place her sitter within the social theater of Parisian leisure <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Theater Box

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Theater Box turns a plush loge into a stage where seeing becomes the performance. A luminous woman—pearls, pale gloves, black‑and‑white stripes—faces us, while her companion scans the auditorium through opera glasses. The painting crystallizes Parisian <strong>modernity</strong> and the choreography of the <strong>gaze</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

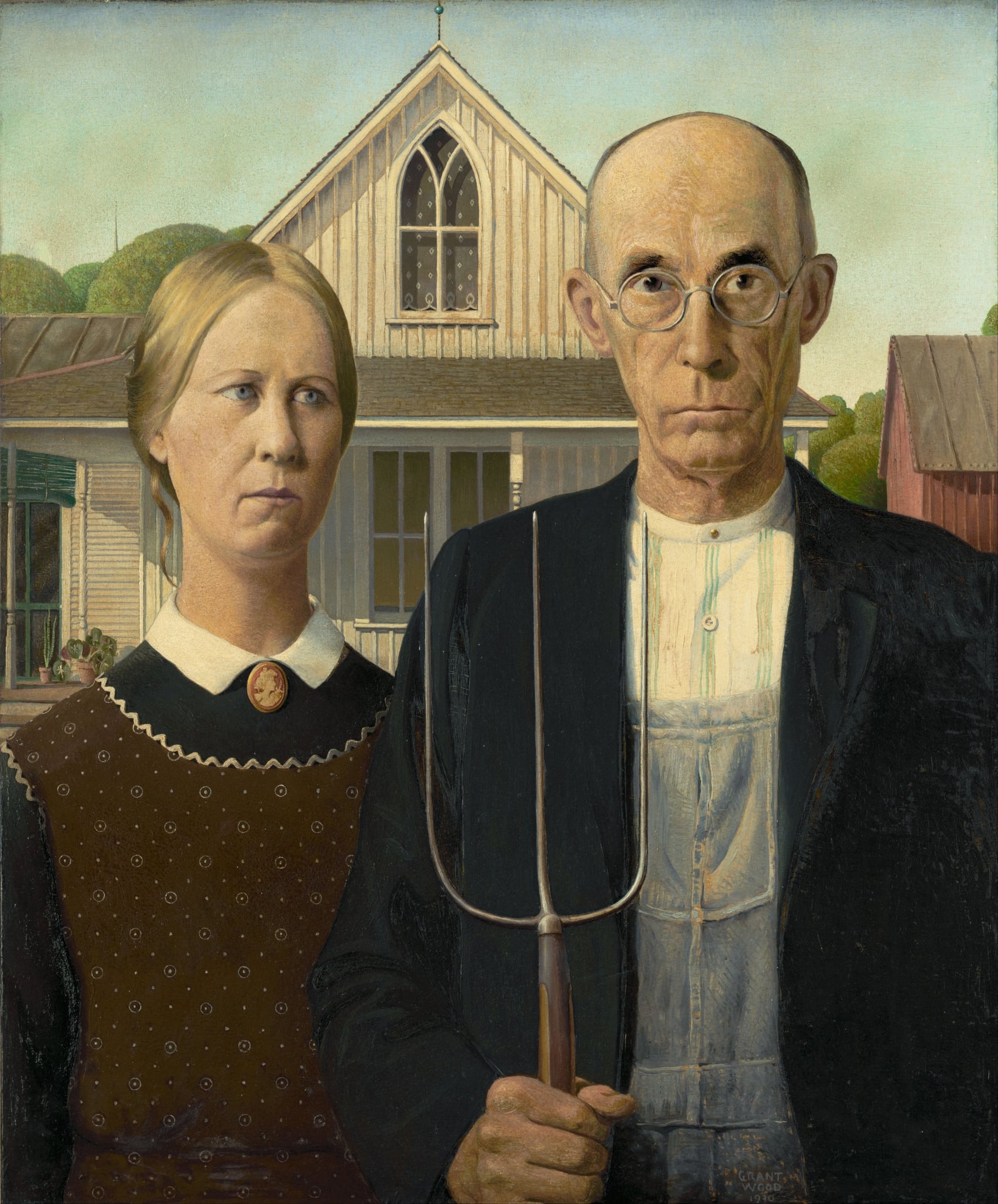

American Gothic

Grant Wood (1930)

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930) turns a plain Midwestern homestead into a <strong>moral emblem</strong> by binding two flinty figures to the strict geometry of a Carpenter Gothic gable and a three‑tined pitchfork. The painting’s cool precision and echoing verticals create a <strong>compressed ethic of work, order, and restraint</strong> that can read as both tribute and critique <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Ballet Rehearsal

Edgar Degas (c. 1874)

In The Ballet Rehearsal, Edgar Degas turns a practice room into a modern drama where <strong>discipline and desire</strong> collide. A dark <strong>spiral staircase</strong> slices the space, scuffed floorboards yawn open, and clusters of dancers oscillate between poised effort and weary waiting <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Kiss

Gustav Klimt (1908 (completed 1909))

The Kiss stages human love as a <strong>sacred union</strong>, fusing two figures into a single, gold-clad form against a timeless field. Klimt opposes <strong>masculine geometry</strong> (black-and-white rectangles) to <strong>feminine organic rhythm</strong> (spirals, circles, flowers), then resolves them in radiant harmony <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Self-Portrait

Mary Cassatt (1878)

In Self-Portrait, Mary Cassatt presents a poised, <strong>modern woman</strong> angled diagonally across a striped chair, her gaze turned away in <strong>thoughtful reserve</strong>. A <strong>sage-olive ground</strong> and tight crop strip away setting, while the <strong>white dress</strong> flickers with lilacs and blues against a <strong>decisive red ribbon</strong> and floral bonnet. The image asserts <strong>professional selfhood</strong> through restraint, asymmetry, and broken color.<sup>[1]</sup>

Liberty Leading the People

Eugene Delacroix (1830)

<strong>Liberty Leading the People</strong> turns a real street uprising into a modern myth: a bare‑breasted Liberty in a <strong>Phrygian cap</strong> thrusts the <strong>tricolor</strong> forward as Parisians of different classes surge over corpses and rubble. Delacroix binds allegory to eyewitness detail—Notre‑Dame flickers through smoke, a bourgeois in a top hat shoulders a musket, and a pistol‑waving boy keeps pace—so that freedom appears as both idea and action <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. After its 2024 cleaning, sharper blues, whites, and reds re‑ignite the painting’s charged color drama <sup>[4]</sup>.

The Elephants

Salvador Dali (1948)

In The Elephants, Salvador Dali distills a stark paradox of <strong>weight and weightlessness</strong>: gaunt elephants tiptoe on <strong>stilt-thin legs</strong> while bearing stone <strong>obelisks</strong>. The blazing red-orange sky and tiny human figures compress ambition into a vision of <strong>precarious power</strong> and time stretched thin <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Gleaners

Jean-Francois Millet (1857)

Three peasant women bend in a solemn rhythm, gleaning leftover stalks under a dry, late-afternoon light. In the far distance, tiny carts, haystacks, and an overseer on horseback signal abundance and authority, while the foreground figures loom with <strong>monumental gravity</strong>, asserting the dignity of labor amid inequality <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror)

Mary Cassatt (ca. 1899)

Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror) turns a routine act of care into a <strong>modern icon</strong>. An oval mirror <strong>haloes</strong> the child while interlaced hands and close bodies make <strong>touch</strong> the vehicle of meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Lovers

Rene Magritte (1928)

René Magritte’s The Lovers turns a kiss into an emblem of <strong>desire obstructed</strong>: two figures—she in red, he in a dark suit—press together while their heads are swathed in <strong>white cloth</strong>. Within a cool blue‑grey interior bounded by crown molding and a rust-red wall, intimacy becomes an image of <strong>opacity</strong> rather than revelation <sup>[1]</sup>.

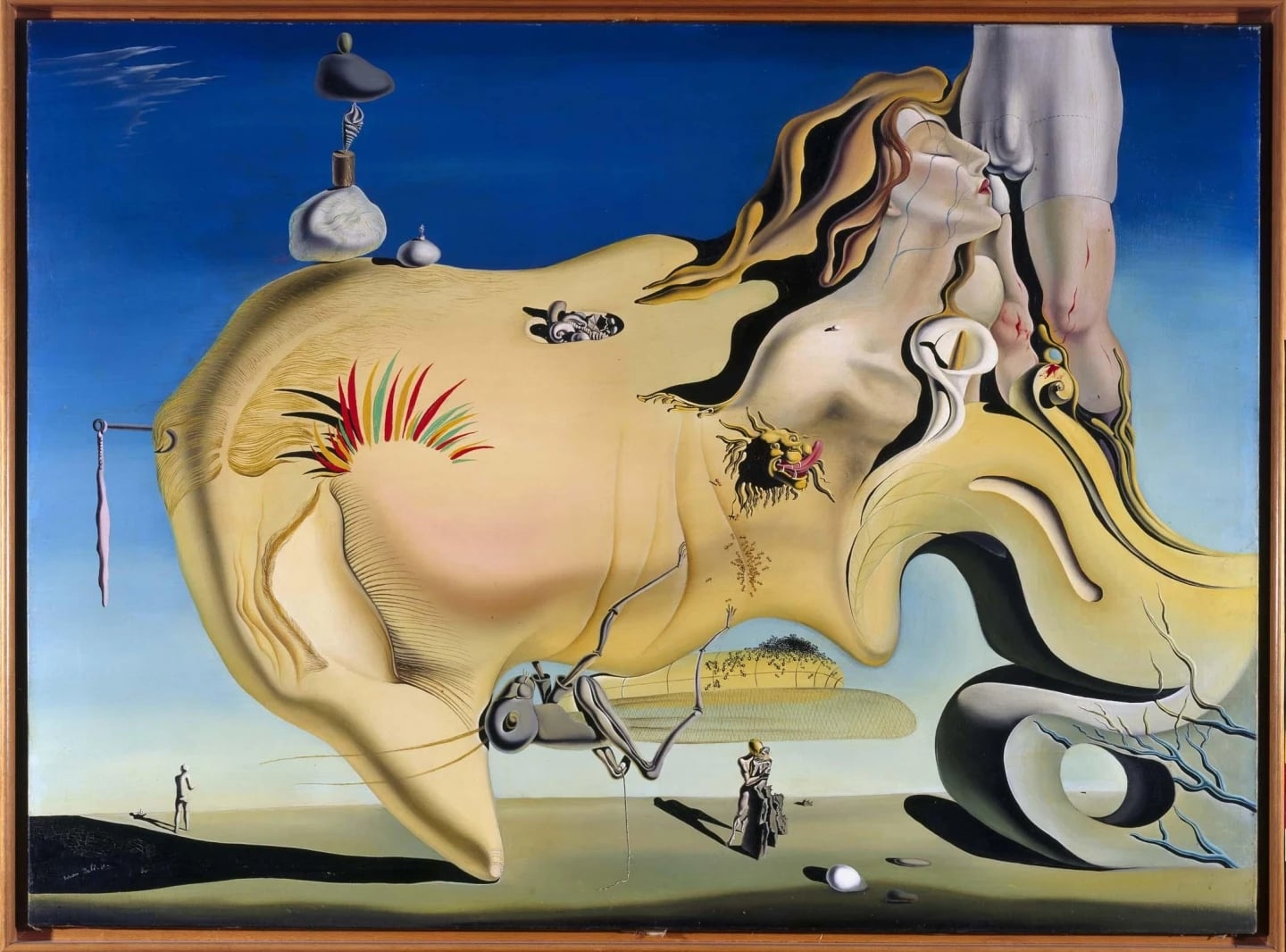

The Great Masturbator

Salvador Dali (1929)

The Great Masturbator condenses Dalí’s newly ignited desire and crippling dread into a single, biomorphic head set against a crystalline Catalan sky. Ants, a gaping grasshopper, a lion’s tongue, a bleeding knee, crutches, stones, and an egg collide to script a confession where <strong>eros</strong> and <strong>decay</strong> are inseparable <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Its precision staging turns autobiography into a <strong>surreal map of compulsion</strong> at the moment Gala enters his life <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Milkmaid

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1660)

In The Milkmaid, Vermeer turns an ordinary act—pouring milk—into a scene of <strong>quiet monumentality</strong>. Light from the left fixes the maid’s absorbed attention and ignites the <strong>saturated yellow and blue</strong> of her dress, while the slow thread of milk becomes the image’s pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Bread, a Delft jug, nail holes, and a small <strong>foot warmer</strong> anchor a world where humble work is endowed with dignity and latent meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

Pablo Picasso (1907)

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon hurls five nudes toward the viewer in a shallow, splintered chamber, turning classical beauty into <strong>sharp planes</strong>, <strong>masklike faces</strong>, and <strong>fractured space</strong>. The fruit at the bottom reads as a sensual lure edged with threat, while the women’s direct gazes indict the beholder as participant. This is the shock point of <strong>proto‑Cubism</strong>, where Picasso reengineers how modern painting means and how looking works <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.