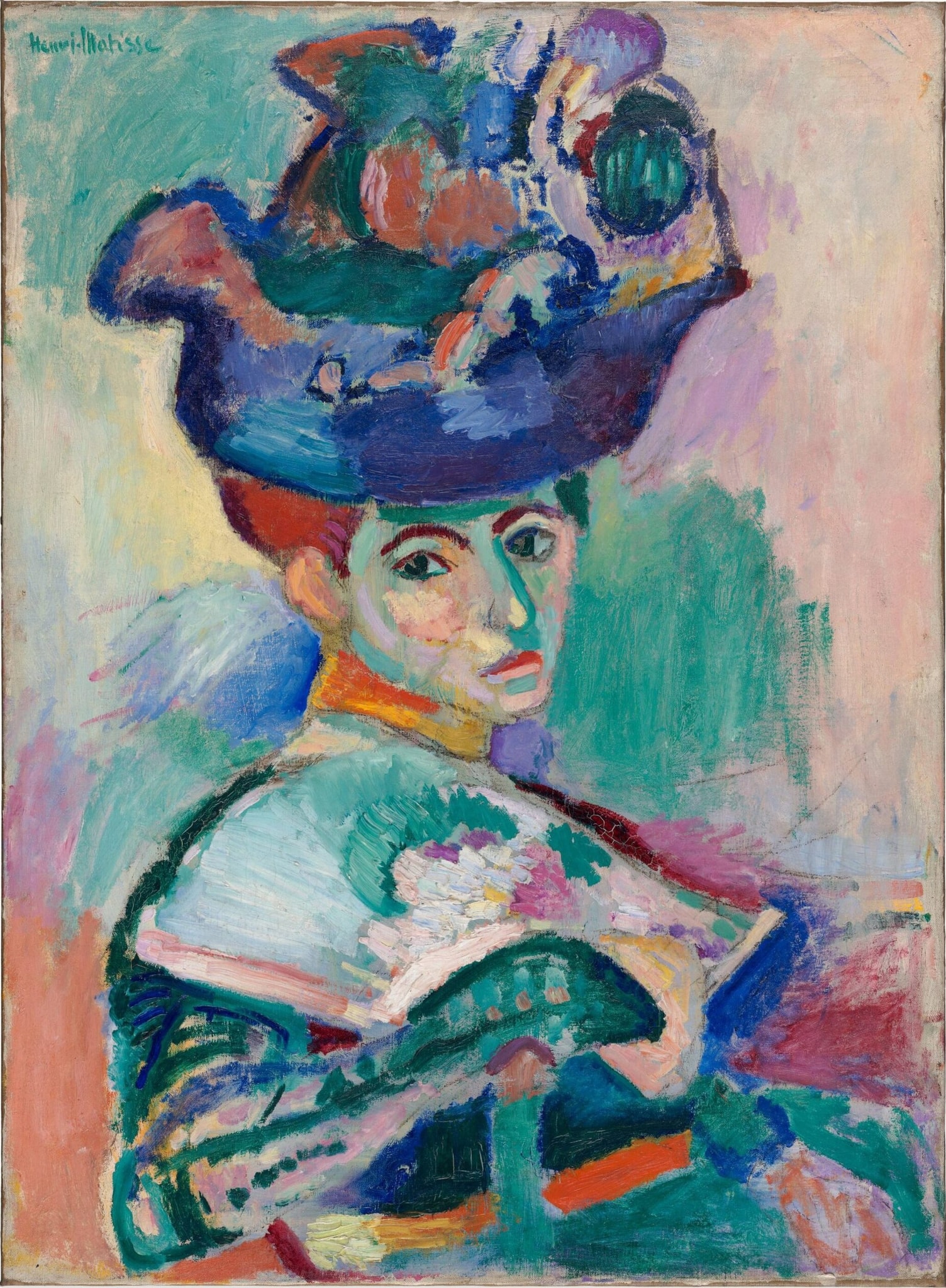

Woman with a Hat

In Woman with a Hat, Henri Matisse turns portraiture into a laboratory for pure color and modern identity. Jagged greens and violets carve the face; the hat detonates into a crown of brushstrokes; a fan slices the torso into bright planes. The result declares Fauvism’s credo: feeling over description [1][2].

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1905

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 80.8 × 59.7 cm

- Location

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Matisse engineers the portrait around a set of decisive visual gambits that unseat naturalism and stage identity as a public act. The sitter’s three‑quarter turn is classic, but tradition ends there: a cool, vertical wedge of green cleaves the face, while violets and yellows counterweight the cheeks, so that color, not shadow, models form. A hot seam of orange along the jaw and neck snaps the head forward against a respirating field of mint and rose, collapsing atmospheric depth into a shallow, pressurized stage. The hat—an outsized escarpment of cobalt, turquoise, and lilac—overruns proportion to become the picture’s engine, its roiling impasto reading as both plume and painted matter. Below, the fan spread across the chest acts as a literal and figurative screen, flattening the body into tessellated strokes and interposing performance between viewer and sitter. Everywhere the brush stays visible and abrupt, building the figure from frictive patches rather than blended tones; space buckles into a living collage that pulls the body toward us even as it frays its edges 12.

Those choices bind fashion, psychology, and pictorial theory. The hat, glove, and fan are bourgeois codes of public presentation, but Matisse overloads them with chromatic voltage so that appearance becomes armor—a modern mask assembled from paint itself. Critics at the Salon read the result as affront and sensation, proof that color could operate independently of description; museums now cite the work as a crystallization of the high‑key method forged with Derain in Collioure that summer, redirected here to portraiture with almost reckless candor 23. The background’s patchwork denies stable ground, keeping the body provisional, as if selfhood were something negotiated in real time between pigments. The sitter’s guarded eyes—dark ovals bracketed by a blue lid and a green nasal trench—hold steady amid the chromatic crossfire, tightening the image’s emotional register without reverting to mimetic comfort. This is not color as decoration but color as structure, tempo, and stance: greens cool the gaze; oranges ignite thresholds; violets soften and then harden planes, setting a tensile rhythm across the canvas 12.

The painting’s historical charge completes its meaning. Shown in the notorious Salle VII in 1905, it helped trigger the critic’s “wild beasts” epithet and the subsequent naming of Fauvism; its purchase by Leo and Gertrude Stein (at 400 rather than the oft‑repeated 500 francs) signaled that the avant‑garde recognized in it a new contract for painting: to tell truths about modern life by intensifying artifice, not suppressing it 15. That contract endures in the way Woman with a Hat still reads today: a portrait whose subject is as much the sitter as the act of seeing—volatile, social, and made in color 23.

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about Woman with a Hat

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

💬 Ask questions about this artwork!

Interpretations

Symbolic Reading: Fashion as Mask and Engine

Rather than accessorizing likeness, the hat, glove, and fan function as semiotic devices that script a bourgeois self for public view. Matisse overloads these signs with saturated, contradictory hues so that fashion becomes a mask, not a mirror: the hat swells into a chromatic crown whose mass nearly engulfs the sitter, while the fan acts as a screen that both flattens and withholds the body. This is portraiture as the staging of codes—dress, deportment, and display—amped by color’s autonomy until the signs begin to misfire, exposing the constructedness of classed femininity. The effect is double: attributes still read as bourgeois, yet their excessive materiality (impasto, abrupt touches) asserts paint’s truth over social polish, making the sitter’s identity legible as a negotiated surface.

Source: The Met; SFMOMA; Tamar Garb (contextual framework)

Formal Analysis: Color as Structure, Not Description

Woman with a Hat radicalizes portrait construction by replacing tonal modeling with chromatic architecture. The green wedge, violet and yellow counterplanes, and orange seam do not imitate light; they build the head as intersecting fields, a practice forged in Collioure and redeployed here with urban candor. Elderfield frames this as Fauvist autonomy of color—a break from Divisionist regularity toward freely orchestrated planes that establish volume, tempo, and edge without recourse to naturalistic shadow. The shallow, agitated ground fuses figure and field, canceling atmospheric recession in favor of a pressurized pictorial stage. Such strategies historicize the painting as a proof‑of‑concept: color is no longer the servant of mimesis but the principal agent of form and meaning.

Source: MoMA/Elderfield; The Met

Psychological Interpretation: Poise Under Pressure

T. J. Clark reads the portrait’s poise as a form of defense—a disciplined, public self (Amélie Matisse) composed under the strain of modern exposure. The hat operates as armor, the fan as comportment; together they stabilize a face traversed by volatile color that threatens to undo likeness. The guarded eyes anchor the field like dark keystones against chromatic crossfire, suggesting vigilance rather than repose. Clark, echoing Spurling’s biography, treats this tension—between catastrophe and control—as the affective core: the subject appears both protected and imperiled by display. In this lens, the work is less a flamboyant color experiment than a portrait of modern nerves, where identity is braced against a world of spectacle and judgment.

Source: T. J. Clark (London Review of Books)

Historical Context: Scandal, Patronage, and Survival

At the 1905 Salon d’Automne, the Salle VII scandal made color’s independence a public flashpoint, but the painting’s fate hinged on patronage. Leo and Gertrude Stein’s purchase—now documented at 400 francs—converted outrage into institutional foothold, underwriting Matisse at a precarious juncture. SFMOMA’s curatorial account also notes the work’s unusual travel restrictions, underscoring its status as a keystone of early Fauvism and of Stein‑era modernism. Situating the picture within this network clarifies its historical agency: the canvas not only named a movement through provocation; it also cemented a new market and discourse for high‑key painting in Paris and, eventually, the United States.

Source: SFMOMA (object record and Janet Bishop, Open Space)

Medium Reflexivity: Painting About Looking

The portrait turns on the act of seeing: conspicuous brushwork, abutted color zones, and a breathing patchwork ground solicit the viewer’s eyes to assemble form in real time. The picture thus performs perception—how color relations, not verisimilitude, deliver coherence. This is a didactic canvas about its own making: every visible stroke insists on facture; every collapse of depth reinstates the surface. Museum readings emphasize how experiments in Collioure become, here, a lesson in urban spectatorship, where the viewer’s look meets the sitter’s calibrated display. The result is a reflexive loop—painting that stages vision as social, unstable, and authored in color.

Source: The Met; SFMOMA; National Gallery of Art (artist overview)

Related Themes

About Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse pivoted around 1904–06 from Divisionist touch to high‑key, liberated color, consolidating this language during the 1905 summer in Collioure and unveiling it to scandal at the Salon d’Automne. His pursuit of color as an autonomous vehicle for structure and feeling became a cornerstone of modern art [2][3].

View all works by Henri Matisse →