Medium reflexivity (art about art)

Featured Artworks

La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume)

Claude Monet (1876)

Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume) (1876) stages a witty confrontation between <strong>Parisian modernity</strong> and the fashion for <strong>Japonisme</strong>. A fair-skinned model in a blazing red uchikake preens before a wall tiled with uchiwa fans, lifting a <strong>tricolor</strong> hand fan that asserts Frenchness amid the imported decor. The painting turns costume, props, and gaze into a performance about <strong>desire, display, and identity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Gustav Klimt (1907)

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I stages its sitter as a <strong>secular icon</strong>—a living presence suspended in a field of gold that converts space into <strong>pattern and power</strong>. The naturalistic face and hands emerge from a reliquary-like cascade of eyes, triangles, and tesserae, turning light, ornament, and status into the painting’s true subjects <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

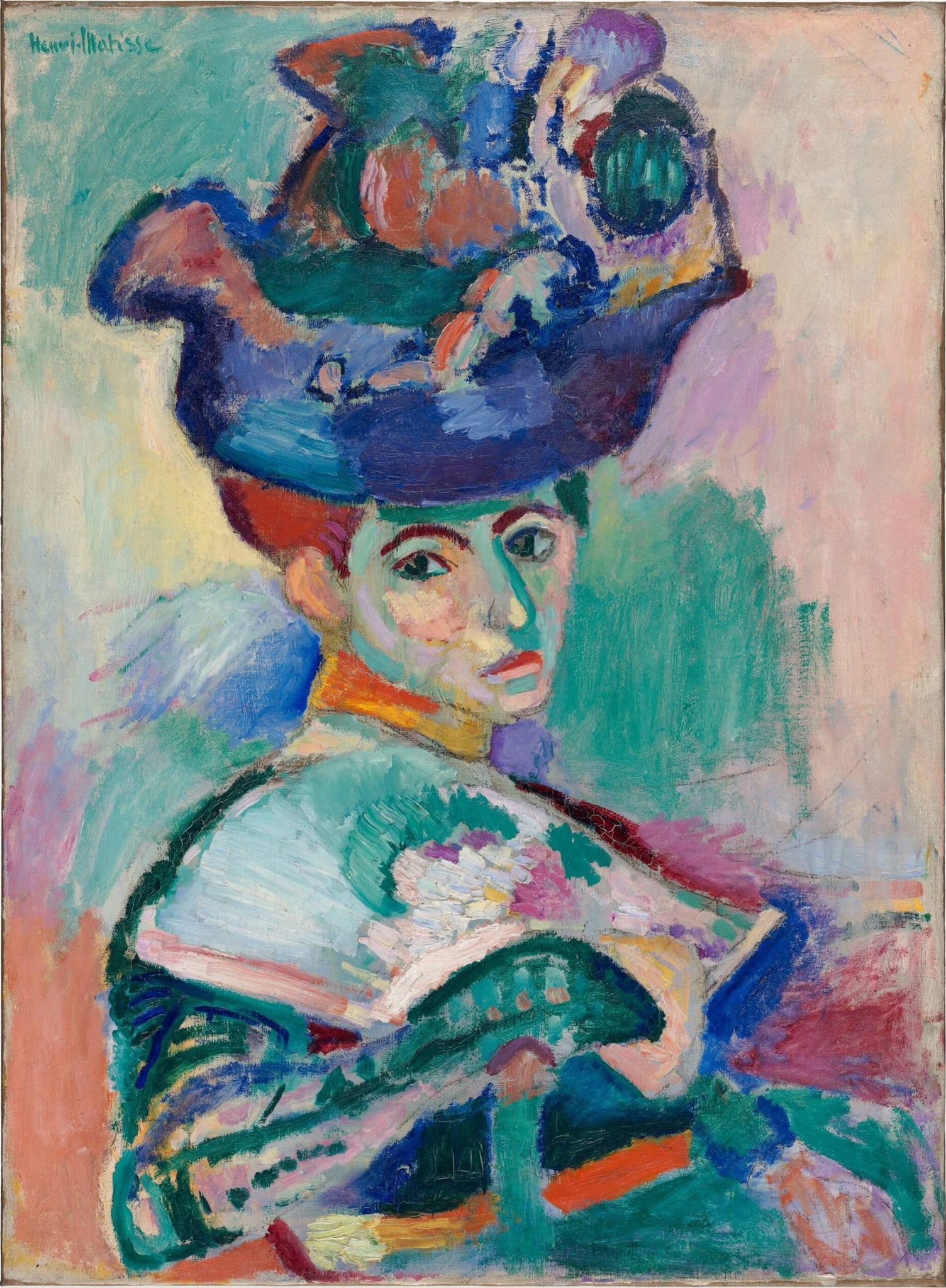

Woman with a Hat

Henri Matisse (1905)

In Woman with a Hat, Henri Matisse turns portraiture into a laboratory for <strong>pure color</strong> and <strong>modern identity</strong>. Jagged greens and violets carve the face; the hat detonates into a crown of brushstrokes; a fan slices the torso into bright planes. The result declares Fauvism’s credo: <strong>feeling over description</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Cradle

Berthe Morisot (1872)

Berthe Morisot’s The Cradle turns a quiet nursery into a scene of <strong>vigilant love</strong>. A gauzy veil, lifted by the watcher’s hand, forms a <strong>protective boundary</strong> that cocoons the sleeping child in light while linking the two figures through a decisive diagonal <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The painting crystallizes modern maternity as a form of attentiveness rather than display—an <strong>unsentimental icon</strong> of care.

The Red Studio

Henri Matisse (1911)

Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911) saturates the artist’s workspace in a continuous field of <strong>Venetian red</strong>, collapsing walls, floor, and furniture into a single chromatic plane. Objects and architecture appear as <strong>mustard-yellow reserve lines</strong> that read like drawing, while Matisse’s own paintings and sculptures retain full color, asserting art’s primacy within the room <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The result is a studio that feels like a <strong>mental map</strong> rather than a literal interior.

The Embroiderer

Johannes Vermeer (1669–1670)

In The Embroiderer, Johannes Vermeer condenses a world of work into a palm‑sized drama of <strong>attention</strong> and <strong>transformation</strong>. A young woman bends over a lace pillow as loose red and white threads spill in front, while a nascent pattern gathers under her poised fingers. Vermeer’s right‑hand light isolates the act of making and turns domestic labor into <strong>virtuous concentration</strong> <sup>[1]</sup>.

Boating

Claude Monet (1887)

Monet’s Boating crystallizes modern leisure as a drama of perception, setting a slim skiff and two pale dresses against a field of dark, mobile water. Bold cropping, a thrusting oar, and the complementary flash of hull and foliage convert a quiet outing into an experiment in <strong>modern vision</strong> and the <strong>materiality of water</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Judith Beheading Holofernes

Caravaggio (1599)

Caravaggio’s Judith Beheading Holofernes stages the biblical execution as a shocking present-tense event, lit by a raking beam that cuts figures from darkness. The <strong>red curtain</strong> frames a moral spectacle in which <strong>virtue overthrows tyranny</strong>, as Judith’s cool determination meets Holofernes’ convulsed resistance. Radical <strong>naturalism</strong>—from tendon strain to ribboning blood—makes deliverance feel material and irreversible.

Haystacks Series by Claude Monet | Light, Time & Atmosphere

Claude Monet

Claude Monet’s <strong>Haystacks Series</strong> transforms a routine rural subject into an inquiry into <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunset view, the stacks swell at the left while the sun burns through the gap, making the field shimmer with <strong>apricot, lilac, and blue</strong> vibrations.

The Card Players by Paul Cézanne | Equilibrium and Form

Paul Cézanne

In The Card Players, Paul Cézanne turns a rural café game into a study of <strong>equilibrium</strong> and <strong>monumentality</strong>. Two hated peasants lean inward across an orange-brown table while a dark bottle stands upright between them, acting as a calm, vertical <strong>axis</strong> that stabilizes their mirrored focus <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Children Playing on the Beach

Mary Cassatt (1884)

In Children Playing on the Beach, Mary Cassatt brings the viewer down to a child’s eye level, granting everyday play the weight of <strong>serious, self-contained work</strong>. The cool horizon and tiny boats open onto <strong>modern space and possibility</strong>, while the cropped, tilted foreground seals us inside the children’s focused world <sup>[1]</sup>.

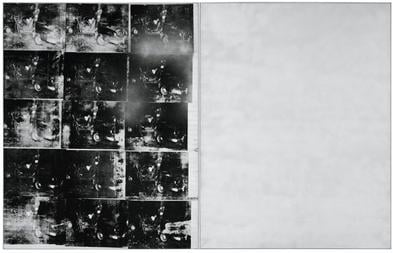

Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster)

Andy Warhol (1963)

Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) pairs a grid of uneven, black‑and‑white silkscreened crash images with a vast, nearly blank field of metallic silver, staging a battle between <strong>relentless spectacle</strong> and <strong>mute void</strong>. Warhol’s industrial repetition converts tragedy into a consumable pattern while the reflective panel withholds detail, forcing viewers to face the limits of representation and the cold afterglow of modern media <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Bathers by Paul Cézanne: Geometry of the Modern Nude

Paul Cézanne

In Bathers, Paul Cézanne arranges a circle of generalized nudes beneath arching trees that meet like a <strong>natural vault</strong>, staging bathing as a timeless rite rather than a specific story. His <strong>constructive brushwork</strong> fuses bodies, water, and sky into one geometric order, balancing cool blues with warm ochres. The scene proposes a measured <strong>harmony between figure and landscape</strong>, a culmination of Cézanne’s search for enduring structure <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Opera Orchestra by Edgar Degas | Analysis

Edgar Degas

In The Opera Orchestra, Degas flips the theater’s hierarchy: the black-clad pit fills the frame while the ballerinas appear only as cropped tutus and legs, glittering above. The diagonal <strong>bassoon</strong> and looming <strong>double bass</strong> marshal a dense field of faces lit by footlights, turning backstage labor into the subject and spectacle into a fragment <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Women in the Garden

Claude Monet (1866–1867)

Claude Monet’s Women in the Garden choreographs four figures in a sunlit bower to test how <strong>white dresses</strong> register <strong>dappled light</strong> and shadow. The path, parasol, and clipped flowers frame a modern ritual of leisure while turning fashion into an instrument of <strong>perception</strong>. The scene reads less as portraiture than as a manifesto for painting the <strong>momentary</strong> outdoors <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Eight Elvises

Andy Warhol (1963)

A sweeping frieze of eight overlapping, gun‑drawn cowboys marches across a silver field, their forms slipping and ghosting as if frames of a film. Warhol converts a singular star into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>, where <strong>mechanical misregistration</strong> and life‑size scale turn bravado into spectacle <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Bacchus

Caravaggio (c. 1598)

Caravaggio’s Bacchus stages a human-scaled god who offers wine with disarming immediacy, yoking <strong>sensual invitation</strong> to <strong>vanitas</strong> warning. The tilted goblet, blemished fruit, and wilting leaves insist that abundance and youth are <strong>precarious</strong>. A private Roman milieu under Cardinal del Monte shaped this refined, provocative image <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Young Girls at the Piano

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892)

Renoir’s Young Girls at the Piano turns a quiet lesson into a scene of <strong>attunement</strong> and <strong>bourgeois grace</strong>. Two adolescents—one seated at the keys, the other leaning to guide the score—embody harmony between discipline and delight, rendered in Renoir’s late, <strong>luminous</strong> touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

![Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] by Andy Warhol](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.googleapis.com%2Fsite-images-programmatic%2Fpaintings%2F1771915343451-6gzg8m.jpg&w=3840&q=85)

Triple Elvis [Ferus Type]

Andy Warhol (1963)

In Triple Elvis [Ferus Type] (1963), Andy Warhol multiplies a gunslinging movie idol across a cool, metallic field, turning a singular persona into a <strong>serial commodity</strong>. The sharply printed figure at center flanked by fading, <strong>ghosted</strong> doubles collapses still image, filmic motion, and mass reproduction into one charged surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Tub

Edgar Degas (1886)

In The Tub (1886), Edgar Degas turns a routine bath into a study of <strong>modern solitude</strong> and <strong>embodied labor</strong>. From a steep, overhead angle, a woman kneels within a circular basin, one hand braced on the rim while the other gathers her hair; to the right, a tabletop packs a ewer, copper pot, comb/brush, and cloth. Degas’s layered pastel binds skin, water, and objects into a single, breathing field of <strong>warm flesh tones</strong> and blue‑greys, collapsing distance between body and still life <sup>[1]</sup>.

Reading Le Figaro

Mary Cassatt (c. 1878–83)

Mary Cassatt’s Reading Le Figaro turns a quiet parlor into a scene of <strong>intellect</strong> and <strong>modern life</strong>. The inverted masthead, mirrored repetition of the paper, and the sitter’s spectacles make <strong>attention</strong>—not appearance—the true subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Through brisk whites and grays, Cassatt dignifies everyday thought as a modern pictorial theme aligned with <strong>Impressionism</strong> <sup>[2]</sup>.

Turquoise Marilyn

Andy Warhol (1964)

In Turquoise Marilyn, Andy Warhol converts a movie star’s face into a <strong>modern icon</strong>: a tightly cropped head floating in a flat <strong>turquoise</strong> field, its <strong>acidic yellow hair</strong>, turquoise eye shadow, and <strong>lipstick-red</strong> mouth stamped by silkscreen’s mechanical bite. The slight <strong>misregistration</strong> around eyes and hair produces a halo-like tremor, fusing <strong>glamour and ghostliness</strong> to expose celebrity as a manufactured surface <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Giverny

Claude Monet (1900)

In The Artist's Garden at Giverny, Claude Monet turns his cultivated Clos Normand into a field of living color, where bands of violet <strong>irises</strong> surge toward a narrow, rose‑colored path. Broken, flickering strokes let greens, purples, and pinks mix optically so that light seems to tremble across the scene, while lilac‑toned tree trunks rhythmically guide the gaze inward <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Water Lilies

Claude Monet (1899)

<strong>Water Lilies</strong> centers on an arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> suspended over a pond where lilies and rippling reflections fuse into a single, vibrating surface. Monet turns the scene into a study of <strong>perception-in-flux</strong>, letting water, foliage, and light dissolve hard edges into atmospheric continuity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Café Terrace at Night

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

In Café Terrace at Night, Vincent van Gogh turns nocturne into <strong>luminous color</strong>: a gas‑lit terrace glows in yellows and oranges against a deep <strong>ultramarine sky</strong> pricked with stars. By building night “<strong>without black</strong>,” he stages a vivid encounter between human sociability and the vastness overhead <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Water Lily Pond

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond transforms a designed garden into a theater of <strong>perception and reflection</strong>. The pale, arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> hovers over a surface where lilies, reeds, and mirrored willow fronds dissolve boundaries between water and sky, proposing <strong>seeing itself</strong> as the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect

Claude Monet (1903 (begun 1900))

Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect renders London as a <strong>lilac-blue atmosphere</strong> where form yields to light. The bridge’s stone arches persist as anchors, yet the span dissolves into mist while <strong>flecks of lemon and ember</strong> signal modern traffic crossing a city made weightless <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Vertical hints of chimneys haunt the distance, binding industry to beauty as the Thames shimmers with the same notes as the sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Morning on the Seine (series)

Claude Monet (1897)

Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine (series) turns dawn into an inquiry about <strong>perception</strong> and <strong>time</strong>. In this canvas, the left bank’s shadowed foliage dissolves into lavender mist while a pale radiance opens at right, fusing sky and water into a single, reflective field <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Summertime

Mary Cassatt (1894)

Mary Cassatt’s Summertime (1894) stages a quiet drama of <strong>attentive looking</strong>: a woman and a girl lean from a cropped boat toward two ducks as the lake flickers with broken color. Cassatt fuses <strong>Impressionism</strong> and <strong>Japonisme</strong>—no horizon, tipped perspective, and abrupt cropping—to press our gaze downward into light-spattered water. The result is an image of <strong>modern leisure</strong> that is also a study of perception itself <sup>[1]</sup>.

Four Marlons

Andy Warhol (1966)

Four Marlons is a 1966 silkscreen by Andy Warhol that multiplies a single biker film-still into a tight 2×2 grid on raw linen. Its inky blacks against a tan, unprimed ground turn the glare of the headlamp, the angled handlebars, and the figure’s guarded pose into a <strong>repeatable icon</strong> of outlaw cool. Warhol’s seriality both <strong>amplifies and drains</strong> the image’s aura, exposing fame as a commodity pattern <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Grand Canal

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s The Grand Canal turns Venice into <strong>pure atmosphere</strong>: the domes of Santa Maria della Salute waver at right while a regiment of <strong>pali</strong> stands at left, their verticals reverberating in the water. The scene asserts <strong>light over architecture</strong>, transforming stone into memory and time into color <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Supper at Emmaus

Caravaggio (1601)

Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus captures the split-second when two disciples recognize Christ in the <strong>breaking of bread</strong>. A raking light isolates Christ’s calm blessing while the disciples erupt—one surging forward with a torn sleeve, the other flinging his arms wide—so the shock of revelation reads as bodily fact. The teetering <strong>basket of fruit</strong> and Eucharistic table amplify themes of abundance and fragility <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

Caspar David Friedrich (ca. 1817)

A solitary figure stands on a jagged crag above a churning <strong>sea of fog</strong>, his back turned in the classic <strong>Rückenfigur</strong> pose. Caspar David Friedrich transforms the landscape into an inner stage where <strong>awe, uncertainty, and resolve</strong> meet at the edge of perception <sup>[3]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Sunflowers

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is a <strong>yellow-on-yellow</strong> still life that stages a full <strong>cycle of life</strong> in fifteen blooms, from fresh buds to brittle seed heads. The thick impasto, green shocks of stem and bract, and the vase signed <strong>“Vincent”</strong> turn a humble bouquet into an emblem of endurance and fellowship <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Japanese Footbridge

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Japanese Footbridge turns his Giverny garden into an <strong>immersive field of perception</strong>: a pale blue-green arc spans water crowded with lilies, while grasses and willows dissolve into vibrating greens. By eliminating the sky and anchoring the scene with the bridge, Monet makes <strong>reflection, passage, and time</strong> the picture’s true subjects <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

Édouard Manet (1882)

Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère stages a face-to-face encounter with modern Paris, where <strong>commerce</strong>, <strong>spectacle</strong>, and <strong>alienation</strong> converge. A composed barmaid fronts a marble counter loaded with branded bottles, flowers, and a brimming bowl of oranges, while a disjunctive <strong>mirror</strong> unravels stable viewing and certainty <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Loge

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Loge (1874) turns an opera box into a <strong>stage of looking</strong>, where a woman meets our gaze while her companion scans the crowd through binoculars. The painting’s <strong>frame-within-a-frame</strong> and glittering fashion make modern Parisian leisure both alluring and self-conscious, turning spectators into spectacles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

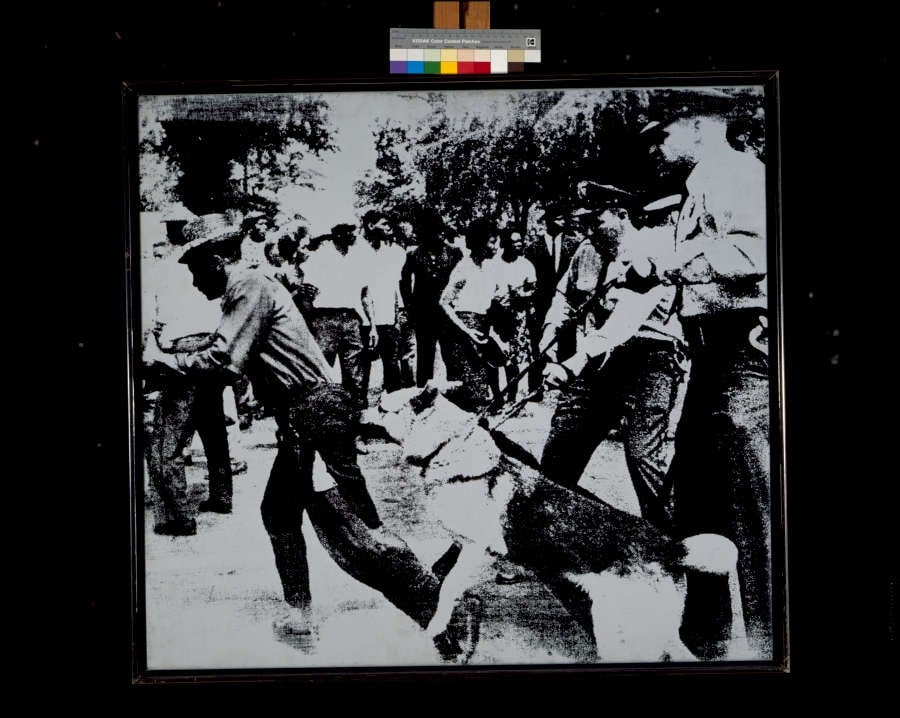

Race Riot

Andy Warhol (1964)

Race Riot crystallizes a split-second of state force: a police dog lunges while officers with batons surge and a ring of onlookers compresses the scene into a <strong>claustrophobic frieze</strong>. Warhol’s stark, high-contrast silkscreen translates a LIFE wire-photo into a <strong>mechanized emblem</strong> of American racial violence and its mass-media circulation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Luncheon on the Grass

Édouard Manet (1863)

Luncheon on the Grass stages a confrontation between <strong>modern Parisian leisure</strong> and <strong>classical precedent</strong>. A nude woman meets our gaze beside two clothed men, while a distant bather and an overturned picnic puncture naturalistic illusion. Manet’s scale and flat, studio-like light convert a park picnic into a manifesto of <strong>modern painting</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Houses of Parliament

Claude Monet (1903)

Claude Monet’s Houses of Parliament renders Westminster as a <strong>dissolving silhouette</strong> in a wash of peach, mauve, and pale gold, where stone and river are leveled by <strong>luminous fog</strong>. Short, vibrating strokes turn architecture into <strong>atmosphere</strong>, while a tiny boat anchors human scale amid the monumental scene.

Rouen Cathedral Series

Claude Monet (1894)

Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral Series (1892–94) turns a Gothic monument into a laboratory of <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunstruck façade, portals, gables, and a warm, orange-tinged rose window flicker in pearly violets and buttery yellows against a crystalline blue sky, while tiny figures at the base anchor the scale. The painting insists that <strong>light—not stone—is the true subject</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Poppies

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Poppies (1873) turns a suburban hillside into a theater of <strong>light, time, and modern leisure</strong>. A red diagonal of poppies counters cool fields and sky, while a woman with a <strong>blue parasol</strong> and a child appear twice along the slope, staging a gentle <strong>echo of moments</strong> rather than a single event <sup>[1]</sup>. The painting asserts sensation over contour, letting broken touches make the day itself the subject.

The Railway

Édouard Manet (1873)

Manet’s The Railway is a charged tableau of <strong>modern life</strong>: a composed woman confronts us while a child, bright in <strong>white and blue</strong>, peers through the iron fence toward a cloud of <strong>steam</strong>. The image turns a casual pause at the Gare Saint‑Lazare into a meditation on <strong>spectatorship, separation, and change</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Olympia

Édouard Manet (1863 (Salon 1865))

A defiantly contemporary nude confronts the viewer with a steady gaze and a guarded pose, framed by crisp light and luxury trappings. In Olympia, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> strips myth from the female nude to expose the <strong>modern economy of desire</strong>, power, and looking <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Beach at Trouville

Claude Monet (1870)

Beach at Trouville turns the Normandy resort into a stage where <strong>modern leisure</strong> meets <strong>restless weather</strong>. Monet’s diagonal boardwalk, wind-whipped <strong>red flags</strong>, and white <strong>parasols</strong> marshal the eye through a day animated by light and air rather than by individual stories <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work asserts Impressionism’s claim to immediacy—there is even <strong>sand embedded in the paint</strong> from working on site <sup>[1]</sup>.

Woman Reading

Édouard Manet (1880–82)

Manet’s Woman Reading distills a fleeting act into an emblem of <strong>modern self-possession</strong>: a bundled figure raises a journal-on-a-stick, her luminous profile set against a brisk mosaic of greens and reds. With quick, loaded strokes and a deliberately cropped <strong>beer glass</strong> and paper, Manet turns perception itself into subject—asserting the drama of a private mind within a public café world <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman Ironing

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1887)

In Woman Ironing, Degas builds a modern icon of labor through <strong>contre‑jour</strong> light and a forceful diagonal from shoulder to iron. The worker’s silhouette, red-brown dress, and the cool, steamy whites around her turn repetition into <strong>ritualized transformation</strong>—wrinkled cloth to crisp order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Vase of Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1889)

Vase of Flowers is a late‑1880s still life in which Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a humble blue‑green jug and a tumbling bouquet into a <strong>laboratory of color and touch</strong>. Against a warm ocher wall and reddish tabletop, coral and vermilion blossoms flare while cool greens and violets anchor the mass, letting <strong>color function as drawing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The work affirms Renoir’s belief that flower painting was a space for bold experimentation that fed his figure art.

The Skiff (La Yole)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1875)

In The Skiff (La Yole), Pierre-Auguste Renoir stages a moment of modern leisure on a broad, vibrating river, where a slender, <strong>orange skiff</strong> cuts across a field of <strong>cool blues</strong>. Two women ride diagonally through the shimmer; an <strong>oar’s sweep</strong> spins a vortex of color as a sailboat, villa, and distant bridge settle the scene on the Seine’s suburban edge <sup>[1]</sup>. Renoir turns motion and light into a single sensation, using a high‑chroma, complementary palette to fuse human pastime with nature’s flux <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

On the Beach

Édouard Manet (1873)

On the Beach captures a paused interval of modern leisure: two fashionably dressed figures sit on pale sand before a <strong>banded, high-horizon sea</strong>. Manet’s <strong>economical brushwork</strong>, restricted greys and blacks, and radical cropping stage a scene of absorption and wind‑tossed motion that feels both intimate and detached <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Cliff Walk at Pourville

Claude Monet (1882)

Claude Monet’s The Cliff Walk at Pourville renders wind, light, and sea as interlocking forces through <strong>shimmering, broken brushwork</strong>. Two small walkers—one beneath a pink parasol—stand near the <strong>precipitous cliff edge</strong>, their presence measuring the vastness of turquoise water and bright sky dotted with white sails. The scene fuses leisure and the <strong>modern sublime</strong>, making perception itself the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Plum Brandy

Édouard Manet (ca. 1877)

Manet’s Plum Brandy crystallizes a modern pause—an urban <strong>interval of suspended action</strong>—through the idle tilt of a woman’s head, an <strong>unlit cigarette</strong>, and a glass cradling a <strong>plum in amber liquor</strong>. The boxed-in space—marble table, red banquette, and decorative grille—turns a café moment into a stage for <strong>solitude within public life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman at Her Toilette

Berthe Morisot (1875–1880)

Woman at Her Toilette stages a private ritual of self-fashioning, not a spectacle of vanity. A woman, seen from behind, lifts her arm to adjust her hair as a <strong>black velvet choker</strong> punctuates Morisot’s silvery-violet haze; the <strong>mirror’s blurred reflection</strong> with powders, jars, and a white flower refuses a clear face. Morisot’s <strong>feathery facture</strong> turns a fleeting toilette into modern subjectivity made visible <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Regatta at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet (1867)

On a brilliant afternoon at the Normandy coast, a diagonal <strong>pebble beach</strong> funnels spectators with parasols toward a bay scattered with <strong>white-sailed yachts</strong>. Monet’s quick, broken strokes set <strong>wind, water, and light</strong> in synchrony, turning a local regatta into a modern scene of leisure held against the vastness of sea and sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Vétheuil

Claude Monet (1881)

Claude Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil stages a sunlit ascent through a corridor of towering sunflowers toward a modest house, where everyday life meets cultivated nature. Quick, broken strokes make leaves and shadows tremble, asserting <strong>light</strong> and <strong>painterly surface</strong> over linear contour. Blue‑and‑white <strong>jardinieres</strong> anchor the foreground, while a child and dog briefly pause on the path, turning the garden into a <strong>domestic sanctuary</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Art of Painting

Johannes Vermeer (c. 1666–1668)

Johannes Vermeer’s The Art of Painting is a self-aware allegory that equates <strong>painting with history and fame</strong>. Framed by a parted <strong>tapestry</strong> like a stage curtain, an artist in historical dress paints the muse <strong>Clio</strong>, while a vast <strong>map of the Seventeen Provinces</strong> and a <strong>double‑headed eagle</strong> chandelier fold national memory into the studio scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Millinery Shop

Edgar Degas (1879–1886)

Edgar Degas’s The Millinery Shop stages modern Paris through a quiet act of <strong>work</strong> rather than display. A young woman, cropped in profile, studies a glowing <strong>orange hat</strong> while faceless stands crowned with ribbons and plumes press toward the picture plane. Degas turns a boutique into a meditation on <strong>labor, commodities, and identity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

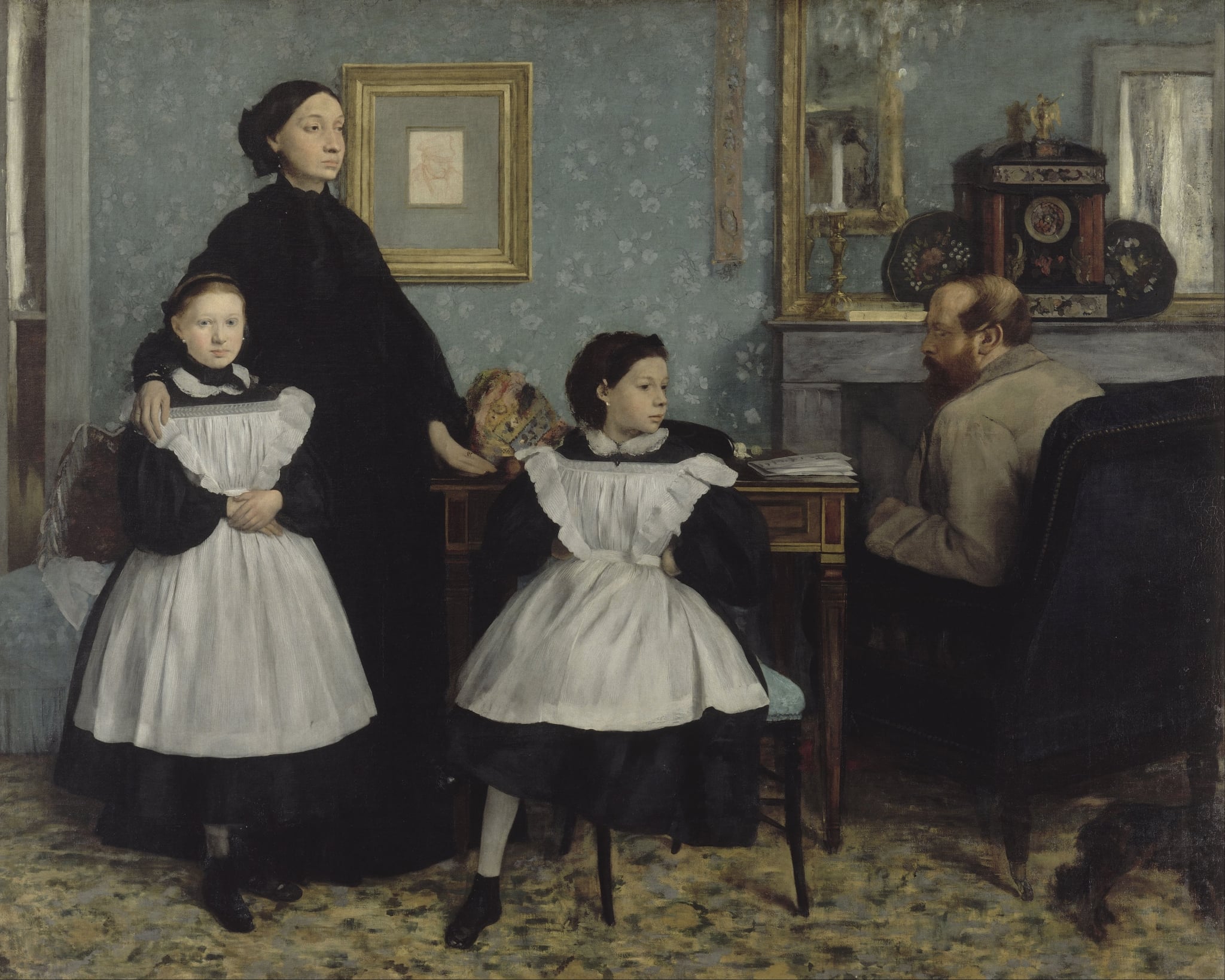

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Star

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1878)

Edgar Degas’s The Star shows a prima ballerina caught at the crest of a pose, her tutu a <strong>vaporous flare</strong> against a <strong>murky, tilted stage</strong>. Diagonal floorboards rush beneath her single pointe, while pale, ghostlike dancers linger in the wings, turning triumph into a scene of <strong>radiant isolation</strong> <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Combing the Hair

Edgar Degas (c.1896)

Edgar Degas’s Combing the Hair crystallizes a private ritual into a scene of <strong>compressed intimacy</strong> and <strong>classed labor</strong>. The incandescent field of red fuses figure and room, turning the hair into a <strong>binding ribbon</strong> between attendant and sitter <sup>[1]</sup>.

Charing Cross Bridge

Claude Monet (1901)

In Charing Cross Bridge, Claude Monet turns London into <strong>atmosphere</strong> itself: the bridge flattens into a cool, horizontal band while mauves, lavenders, and pearly grays veil the city. Spirals of <strong>pink steam</strong> and pockets of pale <strong>blue</strong> read as trains, lamps, or smoke transfigured by weather, so place becomes <strong>sensation</strong> rather than structure.

The Umbrellas

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1881–86)

A sudden shower turns a Paris street into a lattice of <strong>slate‑blue umbrellas</strong>, knitting strangers into a single moving frieze. A bareheaded young woman with a <strong>bandbox</strong> strides forward while a bourgeois mother and children cluster at right, their <strong>hoop</strong> echoing the umbrellas’ arcs <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Music in the Tuileries

Édouard Manet (1862)

Édouard Manet’s Music in the Tuileries turns a Sunday concert into a manifesto of <strong>modern life</strong>: a frieze of top hats, crinolines, and iron chairs flickering beneath <strong>toxic green</strong> foliage. Instead of a hero or center, the painting disperses attention across a restless crowd, making <strong>looking itself</strong> the drama of the scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets

Édouard Manet (1872)

Édouard Manet’s Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets is a close, modern portrait built as a <strong>symphony in black</strong> punctuated by a tiny violet knot. Side‑light chisels the face from a cool, silvery ground while hat, scarf, and coat merge into one dark silhouette, and the eyes are painted strikingly <strong>black</strong> for effect <sup>[1]</sup>. The single touch of violets introduces a discreet, coded <strong>tenderness</strong> within the portrait’s refined restraint <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Dead Toreador

Édouard Manet (probably 1864)

Manet’s The Dead Toreador isolates a matador’s corpse in a stark, horizontal close‑up, replacing the spectacle of the bullring with <strong>silence</strong> and <strong>abrupt finality</strong>. Black costume, white stockings, a pale pink cape, the sword’s hilt, and a small <strong>pool of blood</strong> become the painting’s cool, modern vocabulary of death <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Édouard Manet (1867–1868)

Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian confronts state violence with a <strong>cool, reportorial</strong> style. The wall of gray-uniformed riflemen, the <strong>fragmented canvas</strong>, and the dispassionate loader at right turn the killing into <strong>impersonal machinery</strong> that implicates the viewer <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Sixty Last Suppers

Andy Warhol (1986)

Andy Warhol’s Sixty Last Suppers multiplies Leonardo’s scene into a vast grid, turning a singular sacred image into <strong>serial</strong> signage. From afar it reads as an architectural surface; up close, silkscreen <strong>variations</strong>—blurs, darker panels, dropped ink—reassert the human trace <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Basket of Apples

Paul Cézanne (c. 1893)

Paul Cézanne’s The Basket of Apples stages a quiet drama of <strong>balance and perception</strong>. A tilted basket spills apples across a <strong>rumpled white cloth</strong> toward a <strong>dark vertical bottle</strong> and a plate of <strong>biscuits</strong>, while the tabletop’s edges refuse to align—an intentional play of <strong>multiple viewpoints</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Still Life with Apples and Oranges

Paul Cézanne (c. 1899)

Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples and Oranges builds a quietly monumental world from domestic things. A tilting table, a heaped white compote, a flowered jug, and cascading cloths turn fruit into <strong>durable forms</strong> stabilized by <strong>color relationships</strong> rather than single‑point perspective <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The result is a still life that feels both solid and subtly <strong>unstable</strong>, a meditation on how we construct vision.

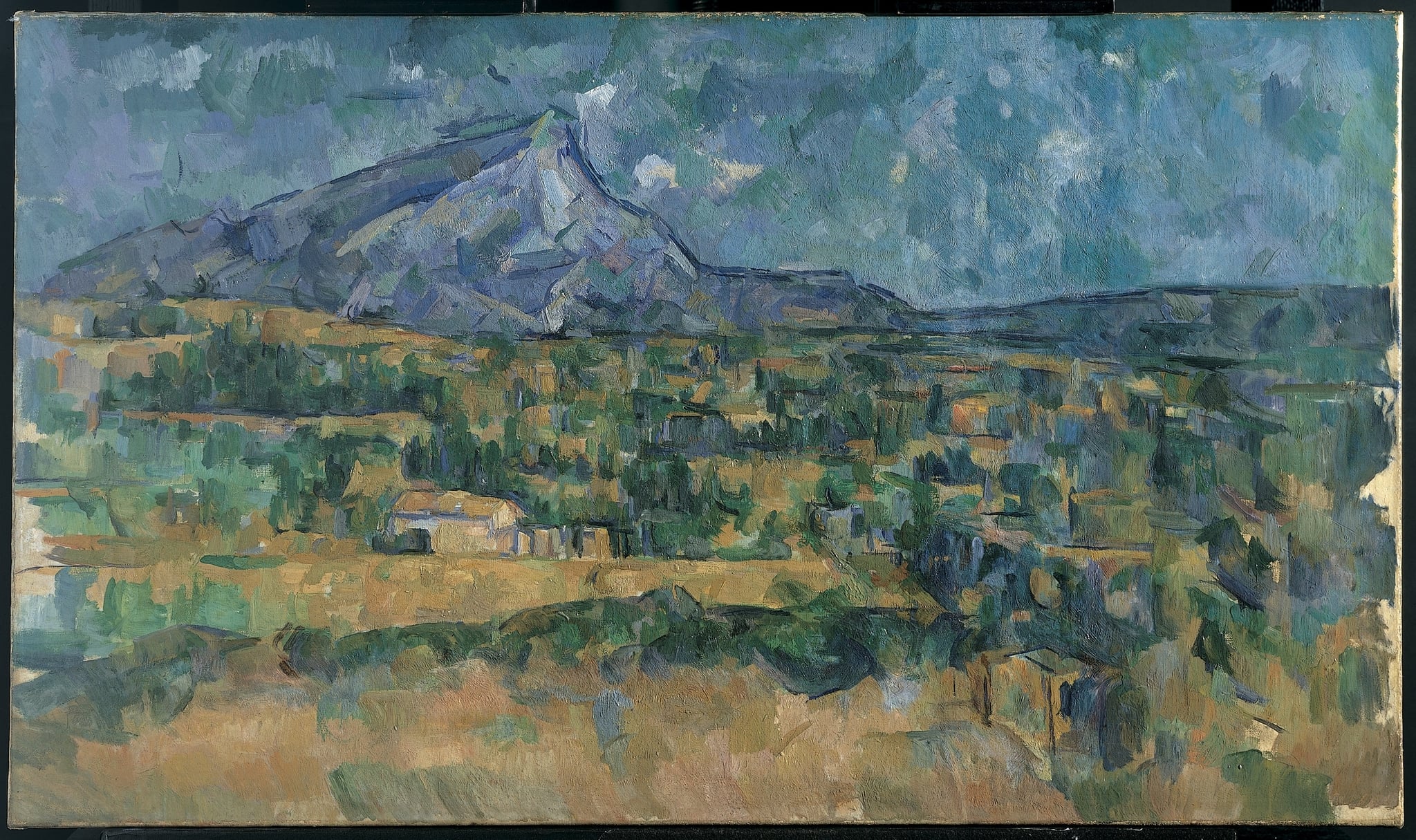

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne (1902–1906)

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire renders the Provençal massif as a constructed order of <strong>planes and color</strong>, not a fleeting impression. Cool blues and violets articulate the mountain’s facets, while <strong>ochres and greens</strong> laminate the fields and blocky houses, binding atmosphere and form into a single structure <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Ambassadors

Hans Holbein the Younger (1533)

Holbein’s The Ambassadors is a double-portrait staged before a green curtain, where shelves of scientific instruments, books, and musical devices enact <strong>Renaissance learning</strong> while an anamorphic <strong>skull</strong> and a veiled <strong>crucifix</strong> counter it with mortality and salvation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work balances worldly status—fur, velvet, Oriental carpet—with a sober theology of limits amid the <strong>Reformation’s discord</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair

Paul Cézanne (about 1877)

Paul Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (about 1877) turns a domestic sit into a study of <strong>color-built structure</strong> and <strong>compressed space</strong>. Cool blue-greens of dress and skin lock against the saturated <strong>crimson armchair</strong>, converting likeness into an inquiry about how painting makes stability visible <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Jane Avril

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (c. 1891–1892)

In Jane Avril, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec crystallizes a public persona from a few <strong>urgent, chromatic strokes</strong>: violet and blue lines whirl into a cloak, while green and indigo dashes crown a buoyant hat. Her face—sharply keyed in <strong>lemon yellow, lilac, and carmine</strong>—hovers between mask and likeness, projecting poise edged with fatigue. The raw brown ground lets her <strong>whiplash silhouette</strong> materialize like smoke from Montmartre’s nightlife.

Portrait of Félix Fénéon

Paul Signac (1890)

Portrait of Félix Fénéon turns a critic into a <strong>conductor of color</strong>: a dandy in a yellow coat proffers a delicate cyclamen as concentric disks, whiplash arabesques, stars, and palette-like circles whirl around him. Rendered in precise <strong>Pointillist</strong> dots, the scene stages the fusion of <strong>art, science, and modern style</strong>.<sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>

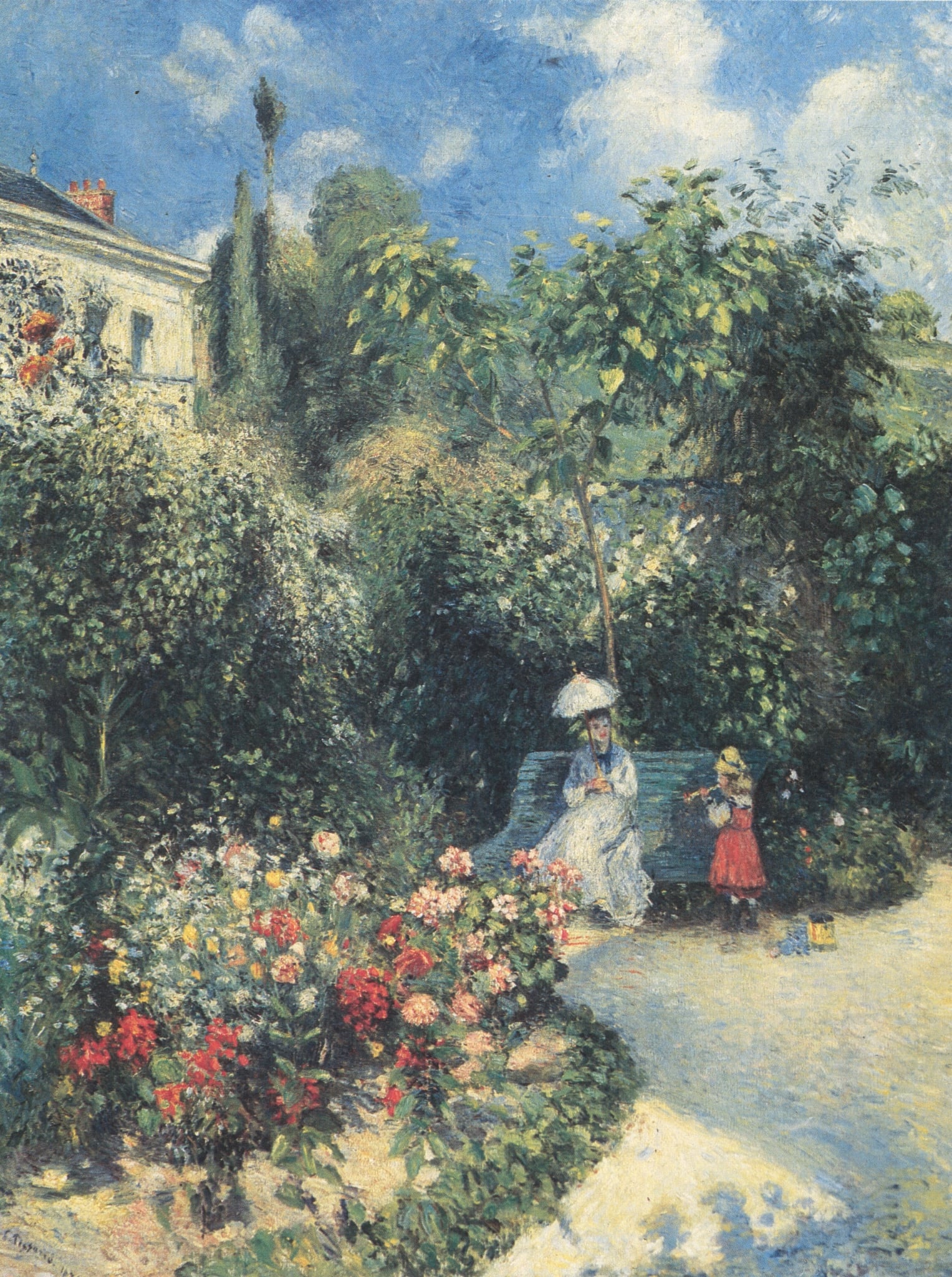

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Harbour at Lorient

Berthe Morisot (1869)

Berthe Morisot’s The Harbour at Lorient stages a quiet tension between <strong>private reverie</strong> and <strong>public movement</strong>. A woman under a pale parasol sits on the quay’s stone lip while a flotilla of masted boats idles across a silvery basin, their reflections dissolving into light. Morisot’s <strong>pearly palette</strong> and brisk brushwork make the water read as time itself, holding stillness and departure in the same breath <sup>[1]</sup>.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair renders a child slumped diagonally across an oversized seat, surrounded by a flotilla of blue chairs and cool window light. With brisk, broken strokes and a skewed recession, Cassatt asserts a modern, unsentimental view of childhood—bored, autonomous, and <strong>out of step with adult decorum</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Subtle collaboration with <strong>Degas</strong> in the background design sharpens the picture’s daring spatial thrust <sup>[2]</sup>.

In the Loge

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s In the Loge (1878) stages modern spectatorship as a drama of <strong>mutual looking</strong>. A woman in dark dress leans forward with <strong>opera glasses</strong>, her <strong>fan closed</strong> on her lap, as a man in the distance raises his own glasses toward her—turning the theater into a circuit of gazes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge

Mary Cassatt (1879)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879) stages modern <strong>spectatorship</strong> inside a plush opera box, where a young woman in pink satin, pearls, and gloves occupies the red velvet seat while a mirror multiplies the chandeliers and balconies. Cassatt fuses <strong>intimacy</strong> and <strong>public display</strong>, using luminous brushwork to place her sitter within the social theater of Parisian leisure <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Cliff, Etretat

Claude Monet (1882–1883)

<strong>The Cliff, Etretat</strong> stages a confrontation between <strong>permanence and flux</strong>: the dark mass of the arch and needle holds like a monument while ripples of coral, green, and blue light skate across the water. The low <strong>solar disk</strong> fixes the instant, and Monet’s fractured strokes make the sea and sky feel like time itself turning toward dusk. The arch reads as a <strong>threshold</strong>—an opening to the unknown that organizes vision and meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Rembrandt van Rijn (1632)

Rembrandt van Rijn turns a civic commission into a drama of <strong>knowledge made visible</strong>. A cone of light binds the ruff‑collared surgeons, the pale cadaver, and Dr. Tulp’s forceps as he raises the <strong>forearm tendons</strong> to explain the hand. Book and body face each other across the table, staging the tension—and alliance—between <strong>textual authority</strong> and <strong>empirical observation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train

Claude Monet (1877)

Claude Monet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train plunges viewers into a <strong>vapor-filled nave of iron and glass</strong>, where billowing steam, hot lamps, and converging rails forge a drama of industrial modernity. The right-hand locomotive, its red buffer beam glowing, materializes out of a <strong>blue-gray atmospheric envelope</strong>, turning motion and time into visible substance <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Boulevard des Capucines

Claude Monet (1873–1874)

From a high perch above Paris, Claude Monet turns the Haussmann boulevard into a living current of <strong>light, weather, and motion</strong>. Leafless trees web the view, crowds dissolve into <strong>flickering strokes</strong>, and a sudden <strong>pink cluster of balloons</strong> pierces the cool winter scale <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Lady at the Tea Table

Mary Cassatt (1883–85 (signed 1885))

Mary Cassatt’s Lady at the Tea Table distills a domestic rite into a scene of <strong>quiet authority</strong>. The sitter’s black silhouette, lace cap, and poised hand marshal a regiment of <strong>cobalt‑and‑gold Canton porcelain</strong>, while tight cropping and planar light convert hospitality into <strong>modern self‑possession</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Theater Box

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Theater Box turns a plush loge into a stage where seeing becomes the performance. A luminous woman—pearls, pale gloves, black‑and‑white stripes—faces us, while her companion scans the auditorium through opera glasses. The painting crystallizes Parisian <strong>modernity</strong> and the choreography of the <strong>gaze</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Piazza San Marco, Venice

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1881)

Renoir’s The Piazza San Marco, Venice redefines St. Mark’s Basilica as <strong>atmosphere</strong> rather than architecture, fusing domes, mosaics, and crowd into vibrating color. Blue‑violet shadows sweep the square while pigeons and passersby resolve into <strong>daubs of light</strong>, declaring modern vision as the true subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Girls at the Seashore

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c.1890–1894)

Girls at the Seashore presents two young figures reclining on a grassy bank, their straw hats trimmed with flowers as they look toward a hazy waterway flecked with small sails. Renoir fuses figure and setting through soft, vaporous brushwork so that skin, fabric, foliage, and sea share the same light. The image is an ode to <strong>reverie</strong>, <strong>companionship</strong>, and the <strong>fleeting</strong> warmth of summer.

Still Life with Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers (1885) sets a jubilant bouquet in a pale, crackled vase against softly dissolving wallpaper and a wicker screen. With quick, clear strokes and a centered, oval mass, the painting unites <strong>Impressionist color</strong> with a <strong>classical, post-Italy structure</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The slight droop of blossoms turns the domestic scene into a gentle <strong>vanitas</strong>—a savoring of beauty before it fades <sup>[5]</sup>.

Children on the Seashore, Guernsey

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1883)

Renoir’s Children on the Seashore, Guernsey crystallizes a wind‑bright moment of modern leisure with <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a gently choreographed group of children. The central girl in a white dress and black feathered hat steadies a toddler while a pink‑clad companion leans in and a sailor‑suited boy rests on the pebbles—an intimate triangle set against a <strong>shimmering, populated sea</strong>. The canvas makes light and movement the protagonists, dissolving edges into <strong>pearly surf and sun‑washed cliffs</strong>.

The Kiss

Gustav Klimt (1908 (completed 1909))

The Kiss stages human love as a <strong>sacred union</strong>, fusing two figures into a single, gold-clad form against a timeless field. Klimt opposes <strong>masculine geometry</strong> (black-and-white rectangles) to <strong>feminine organic rhythm</strong> (spirals, circles, flowers), then resolves them in radiant harmony <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Birth of Venus

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1484–1486)

In The Birth of Venus, <strong>Sandro Botticelli</strong> stages the sea-born goddess arriving on a <strong>scallop shell</strong>, blown ashore by intertwined <strong>winds</strong> and greeted by a flower-garlanded attendant who lifts a <strong>rose-patterned mantle</strong>. The painting’s crisp contours, elongated figures, and gilded highlights transform myth into an <strong>ideal of beauty</strong> that signals love, spring, and renewal <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Las Meninas

Diego Velazquez (1656)

In Las Meninas, a luminous Infanta anchors a shadowed studio where the painter pauses at a vast easel and a small wall mirror reflects the monarchs. The scene folds artist, sitters, and viewer into one reflexive tableau, turning court protocol into a meditation on <strong>seeing and being seen</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. A bright doorway at the rear deepens space and time, as if someone has just entered—or is leaving—the picture we occupy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The School of Athens

Raphael (1509–1511)

Raphael’s The School of Athens orchestrates a grand debate on knowledge inside a perfectly ordered, classical hall whose one-point perspective converges on the central pair, <strong>Plato</strong> and <strong>Aristotle</strong>. Their opposed gestures—one toward the heavens, one level to the earth—establish the fresco’s governing dialectic between <strong>ideal forms</strong> and <strong>empirical reason</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Around them, mathematicians, scientists, and poets cluster under statues of <strong>Apollo</strong> and <strong>Athena/Minerva</strong>, turning the room into a temple of <strong>Renaissance humanism</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper (1942)

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks turns a corner diner into a sealed stage where <strong>fluorescent light</strong> and <strong>curved glass</strong> hold four figures in suspended time. The empty streets and the “PHILLIES” cigar sign sharpen the sense of <strong>urban solitude</strong> while hinting at wartime vigilance. The result is a cool, lucid image of modern life: illuminated, open to view, and emotionally out of reach.

The Third of May 1808

Francisco Goya (1814)

Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 turns a specific reprisal after Madrid’s uprising into a universal indictment of <strong>state violence</strong>. A lantern’s harsh glare isolates a civilian who raises his arms in a <strong>cruciform</strong> gesture as a faceless firing squad executes prisoners, transforming reportage into <strong>modern anti-war testimony</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck (1434)

In The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck stages a poised encounter between a richly dressed couple whose joined hands, a single burning candle, and a convex mirror transform a domestic interior into a scene of <strong>status and sanctity</strong>. The painting asserts the artist’s own <strong>presence</strong>—"Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434"—as if to validate the moment while showcasing oil painting’s power to make belief tangible through light, texture, and reflection <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Whistler's Mother

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1871)

Whistler's Mother is an <strong>austere orchestration of tone and geometry</strong> that turns a private sitting into a public monument. The strict profile, black dress, and white lace are set against flat greys, a patterned curtain, and a framed Thames print to create <strong>measured balance and silence</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Hokusai (ca. 1830–32)

The Great Wave off Kanagawa distills a universal drama: fragile laboring boats face a <strong>towering breaker</strong> while <strong>Mount Fuji</strong> sits small yet immovable. Hokusai wields <strong>Prussian blue</strong> to sculpt depth and cold inevitability, fusing ukiyo‑e elegance with Western perspective to stage nature’s power against human resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Son of Man

Rene Magritte (1964)

Rene Magritte’s The Son of Man stages a crisp <strong>everyman</strong> in bowler hat and overcoat before a sea horizon while a <strong>green apple</strong> hovers to block his face. The tiny glimpse of one eye above the fruit turns a straightforward portrait into a <strong>riddle about seeing and knowing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Self-Portrait

Mary Cassatt (1878)

In Self-Portrait, Mary Cassatt presents a poised, <strong>modern woman</strong> angled diagonally across a striped chair, her gaze turned away in <strong>thoughtful reserve</strong>. A <strong>sage-olive ground</strong> and tight crop strip away setting, while the <strong>white dress</strong> flickers with lilacs and blues against a <strong>decisive red ribbon</strong> and floral bonnet. The image asserts <strong>professional selfhood</strong> through restraint, asymmetry, and broken color.<sup>[1]</sup>

This is Not a Pipe

Rene Magritte (1929)

A crisply modeled tobacco pipe hovers over a blank beige field, while the cursive line "Ceci n’est pas une pipe" coolly denies what the eye assumes. The clash between image and sentence turns a familiar object into a <strong>thought experiment</strong> about signs and things. Magritte’s deadpan exactitude and ad‑like layout stage a <strong>philosophical trap</strong>: you can see a pipe, but you cannot smoke this picture. <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>

Swans Reflecting Elephants

Salvador Dali (1937)

Swans Reflecting Elephants stages a calm Catalan lagoon where three swans and a thicket of bare trees flip into monumental <strong>elephants</strong> in the mirror of water. Salvador Dali crystallizes his <strong>paranoiac-critical</strong> method: a meticulously painted illusion that makes perception generate its own doubles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work locks grace to gravity, surface to depth, turning the lake into a theater of <strong>metamorphosis</strong>.

No. 5, 1948

Jackson Pollock (1948)

<strong>No. 5, 1948</strong> is a large, floor‑painted field of poured enamel where tangled skeins of black, gray, umber, and bursts of yellow span the entire support. Its <strong>all‑over</strong> structure rejects a central motif, turning the painting into a record of motion and material behavior. The result is a charged surface that reads as both <strong>image and event</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Jewish Bride

Rembrandt van Rijn (c. 1665–1669)

The Jewish Bride by Rembrandt van Rijn stages an intimate covenant: two figures, read today as <strong>Isaac and Rebecca</strong>, seal their union through touch rather than spectacle. Light concentrates on faces and hands, while the man’s glittering <strong>gold sleeve</strong> and the woman’s <strong>coral-red gown</strong> turn paint itself into a metaphor for fidelity and tenderness <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. This late masterpiece embodies Rembrandt’s <strong>material eloquence</strong>—impasto as feeling—within a hushed, dark setting <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Campbell's Soup Cans

Andy Warhol (1962)

Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans turns a shelf-staple into <strong>art</strong>, using a gridded array of near-identical red-and-white cans to fuse <strong>branding</strong> with <strong>painting</strong>. By repeating 32 flavors—Tomato, Clam Chowder, Chicken Noodle, and more—the work stages a clash between <strong>mass production</strong> and the artist’s hand <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Marilyn Diptych

Andy Warhol (1962)

Marilyn Diptych crystallizes the paradox of fame: <strong>dazzling allure</strong> and <strong>inevitable decay</strong>. Warhol’s 50 repeated silkscreens—color at left, fading grayscale at right—turn a movie-star headshot into a mass-produced <strong>icon</strong> and a memento of mortality <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Lovers

Rene Magritte (1928)

René Magritte’s The Lovers turns a kiss into an emblem of <strong>desire obstructed</strong>: two figures—she in red, he in a dark suit—press together while their heads are swathed in <strong>white cloth</strong>. Within a cool blue‑grey interior bounded by crown molding and a rust-red wall, intimacy becomes an image of <strong>opacity</strong> rather than revelation <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Manneporte near Étretat

Claude Monet (1886)

Monet’s The Manneporte near Étretat turns the colossal sea arch into a <strong>threshold of light</strong>: rock, sea, and air interlock as shifting color rather than fixed form. Dense lilac–ochre strokes make the cliff feel massive yet <strong>dematerialized</strong> by illumination, while the arch’s opening stages a quiet, glimmering horizon <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

La Grenouillère

Claude Monet (1869)

Monet’s La Grenouillère crystallizes the new culture of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine: crowded bathers, promenading couples, and rental boats orbit a floating resort. With <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a high-key palette, Monet turns water, light, and movement into the true subjects, suspending the scene at the brink of dissolving.