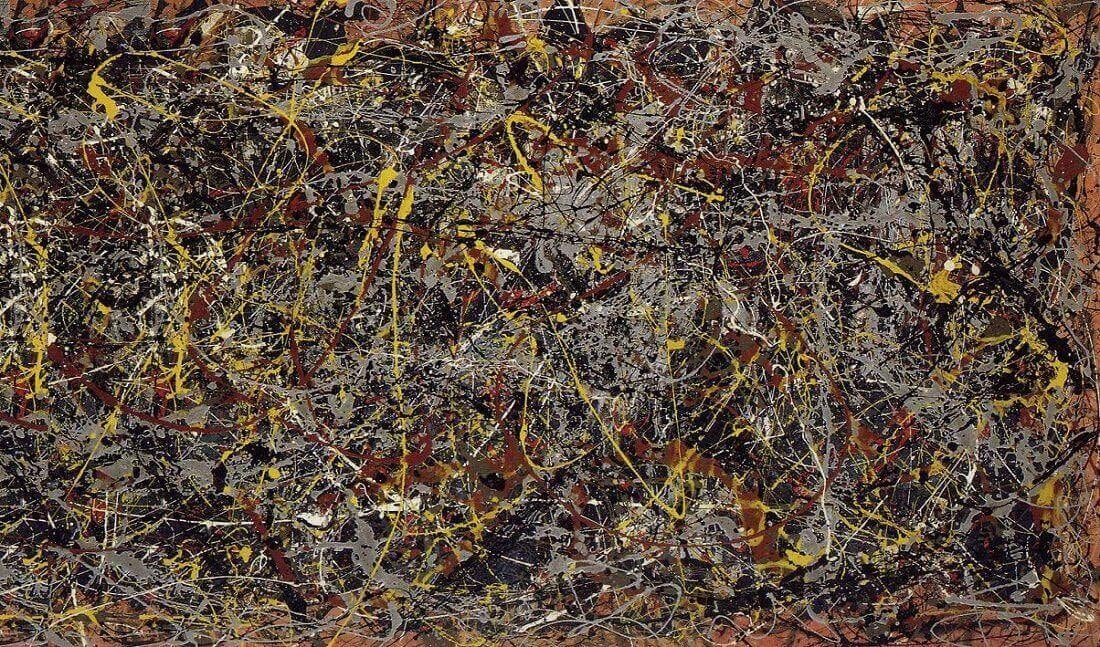

No. 5, 1948

No. 5, 1948 is a large, floor‑painted field of poured enamel where tangled skeins of black, gray, umber, and bursts of yellow span the entire support. Its all‑over structure rejects a central motif, turning the painting into a record of motion and material behavior. The result is a charged surface that reads as both image and event [1][2][3].

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1948

- Medium

- Oil, enamel, and aluminum paint on fiberboard

- Dimensions

- 243.8 × 121.9 cm (8 × 4 ft)

- Location

- Private collection

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Seen up close, No. 5, 1948 offers no resting center: thick umbers at the perimeter frame a continuous lattice where black and gunmetal lines knot and unspool, while quick ribbons of yellow streak diagonally across the field. Silvery filaments—likely aluminum paint—catch the light and slip over darker strata, confirming a stepwise choreography of layers. This centerless saturation enacts what Clement Greenberg praised as an all‑over order that suppresses hierarchy yet heightens optical unity; every inch is equally activated, so meaning resides in the pictorial system itself rather than in depicted objects 3.

At the same time, the painting operates exactly as Harold Rosenberg proposed: the canvas is an arena in which to act. The arcing lines register Pollock’s swings of the arm and wrist, but the evenness of the filaments and their avoidance of big droplets show controlled flow rather than accident. Fluid‑mechanics studies confirm that Pollock managed paint speeds and heights to keep strands coherent, negotiating between chance and intention. In No. 5, 1948 the long, taut whips of yellow that cross from lower left to upper right, and the looping gray cords that skim just above them, document a series of decisions about tempo, viscosity, and direction—decisions that become the work’s content 25.

Pollock’s procedure also transforms the picture plane into a temporal record. You can read the layers: darker, thicker black and umber form a matted substrate; over this, lighter grays and silvers weave a cooler mesh; last, sharper yellow and rusty red punctuation puncture the web. The eye tracks these episodes like measures in music, so the painting is less an image of something than a lived sequence of gestures. That is why viewers often sense both anxiety and exuberance here: the density at the center compresses energy while the elastic yellow arcs release it outward. The work thus mirrors postwar uncertainty—not by symbol but by structure—while asserting a will to create order from turbulence 124.

Scholars have noted that vestiges of figuration sometimes persist in Pollock’s late‑1940s matrices. In No. 5, 1948, however, any head‑ or body‑like hints dissolve before they settle, reinforcing the painting’s commitment to process over iconography. What remains legible are material facts: enamel and aluminum on fiberboard; the large 8‑by‑4‑foot scale that demands bodily movement; the floor‑based method developed in Springs, New York. Even the work’s biography intensifies its meaning: damaged in delivery and then reworked, No. 5, 1948 literally embodies revision by action, folding contingency into its final surface 467.

As a landmark of Abstract Expressionism, the painting consolidates multiple breakthroughs at once: all‑over composition, action as subject, and a modern industrial palette that mixes earthy umbers with metallic grays. Its influence is twofold—formal and methodological. Formally, it validates the entire surface as field; methodologically, it legitimizes process as narrative. In No. 5, 1948, Pollock shows that a painting can mean by how it is made, and that is precisely why the work continues to anchor debates about authorship, control, and the limits of pictorial representation 2345.

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about No. 5, 1948

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

💬 Ask questions about this artwork!

Interpretations

Formal Debate: All‑Overness vs. Action

No. 5, 1948 sits at the crux of two classic postwar accounts. For Clement Greenberg, its all‑over field advances modernist flatness, dispersing hierarchy so that optical unity supplants narrative 3. For Harold Rosenberg, the very same surface reads as an event, the canvas an “arena” where meaning is produced in action—not illustration 2. Pollock’s tight filaments and even distribution reconcile these positions: the painting is formally autonomous yet palpably performed. In this dual reading, the “image” is a by‑product of operations (walking, whipping, pausing), while the pictorial system stabilizes those acts into a coherent totality. The tension between these frameworks is productive: it shows how Pollock converts gesture into structure without relinquishing the experiential charge of performance 23.

Source: Clement Greenberg; Harold Rosenberg

Materials/Physics: Controlled Flow, Industrial Shine

Pollock’s skeins are not accidents but the result of controlled flow. Fluid‑mechanics studies demonstrate he tuned height, speed, and viscosity to keep strands continuous and avoid droplet breakup, producing those taut, lunging lines 4. The use of aluminum paint introduces a specular layer whose reflectivity modulates perception as viewers move, shifting the web’s hierarchy in real time. Academic records identify oil, enamel, and aluminum on fiberboard, underscoring the work’s industrial palette and support 5. These material facts extend meaning: the painting fuses painterly tradition with postwar technologies, turning viscosity, drying time, and reflectance into compositional variables. In No. 5, 1948, matter behaves like choreography; physics underwrites intention 45.

Source: Brown University Engineering; University of Michigan Visual Resources Collection

Process Biography: Damage, Revision, and Aura

The painting’s “life” amplifies its content. After its 1949 sale to Alfonso Ossorio, the surface was reportedly damaged in transit; Pollock first patched it, then undertook more extensive reworking when Ossorio noticed issues 6. This episode folds contingency into the final image, making revision-by-action part of its ontology. Later, the work’s high‑profile 2006 private sale (price widely reported; ownership undisclosed) removed it from public circulation, intensifying its aura as a rumored, almost mythical object 7. The biography thus mirrors the canvas’s own logic: a record of events—accident, repair, exchange—inscribed not only in paint but in provenance. No. 5, 1948 is both artifact and after‑image of the acts that made and remade it 67.

Source: Smithsonian Archives of American Art (Grace Hartigan oral history); UPI/AP market reporting

Residual Figuration: Seeing Through the Web

MoMA scholarship (Varnedoe with Pepe Karmel) shows that Pollock’s late‑1940s matrices sometimes retain vestiges of figuration—heads, bodies—ghosted within the linear net 1. In No. 5, 1948, any emergent silhouettes tend to dissolve before stabilization, reinforcing the work’s commitment to process over iconography. Yet this very near‑legibility matters: the eye repeatedly “tests” the field for figures, only to be routed back into pattern and layer. The perceptual back‑and‑forth becomes content, dramatizing the threshold between automatism and constructed order. Rather than a code to be cracked, the painting offers a disciplined refusal of fixable imagery, keeping vision in a state of productive uncertainty 1.

Source: MoMA (Varnedoe with Pepe Karmel, 1998 retrospective scholarship)

Perception Science: Fractals and Their Limits

Physicist Richard Taylor and colleagues argue Pollock’s webs exhibit evolving fractal characteristics, possibly contributing to their perceptual appeal by echoing natural scaling patterns 8. Subsequent critiques caution against using fractal metrics for authentication and question the sufficiency of the evidence, positioning such analyses as supplementary rather than determinative 9. For No. 5, 1948, the point isn’t to prove authorship by math but to register how viewers might experience the field’s scale‑invariance—finding order within density, coherence within apparent chaos. Fractals become a heuristic for why the surface feels alive as one zooms in and out, dovetailing with art‑historical claims about all‑overness without replacing them 89.

Source: Nature; Scientific American

Related Themes

About Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) developed his poured enamel method in the late 1940s in his Springs, NY studio, laying supports on the floor and working with industrial paints to record sweeping bodily gestures. His approach—publicized soon after in a 1949 LIFE feature—helped define Abstract Expressionism and reoriented painting toward process and performance [4].

View all works by Jackson Pollock →