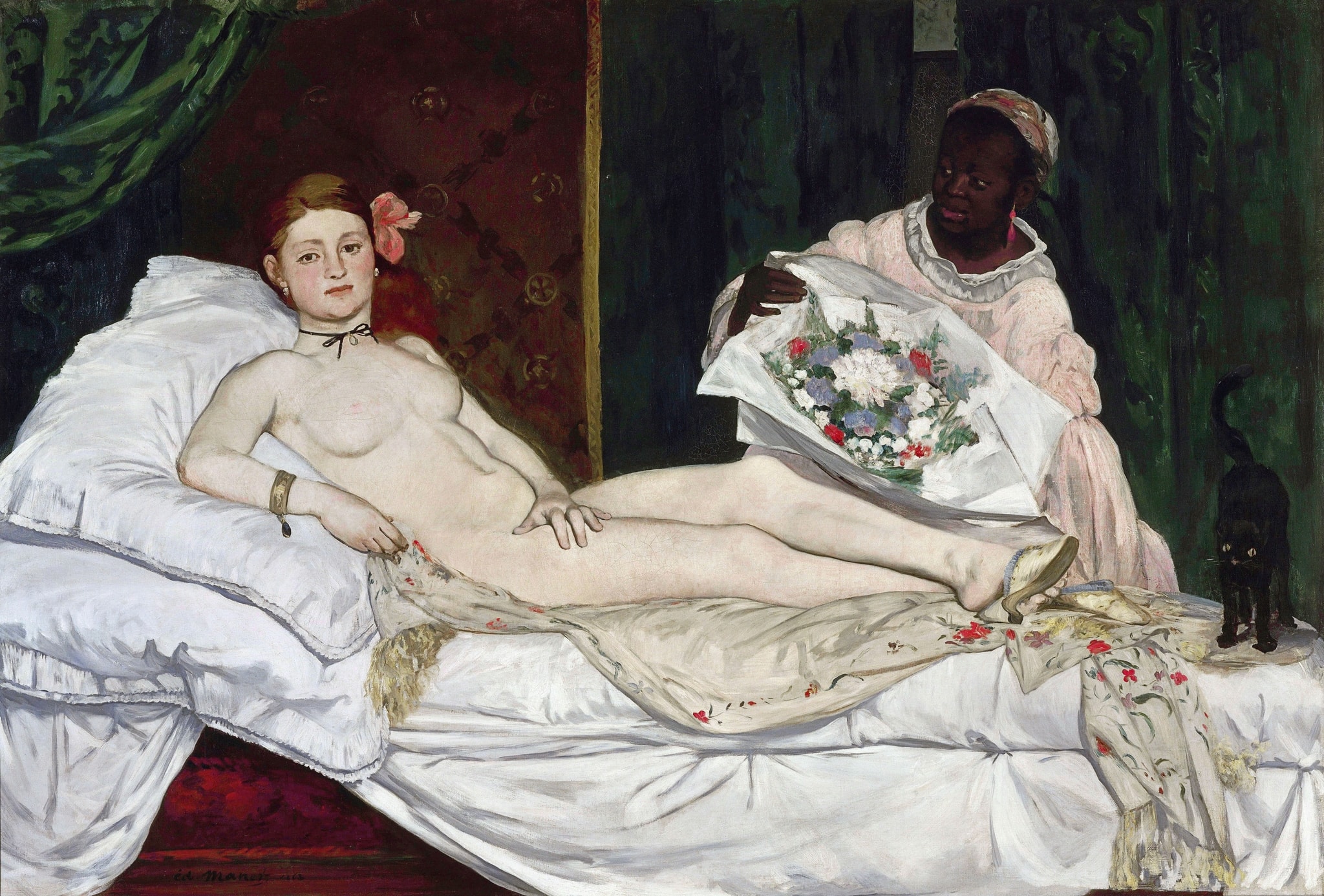

Olympia

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1863 (Salon 1865)

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 130.5 × 191 cm

- Location

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

The meaning of Olympia is a deliberate unmasking of the nude as a modern transaction: the direct gaze, the blocking hand, and the gift-bouquet convert desire into terms of price, choice, and power 13. It matters because Manet turns spectatorship itself into the subject, forcing the viewer to meet a woman who controls the terms of visibility rather than embodying passive ideal beauty 34. The painting also stages race and labor at the heart of Parisian modernity through the presence and agency of Laure, the Black maid, whose role anchors the scene in contemporary social relations 56. As a result, Olympia becomes a foundational image of painting modern life, anticipating modernism’s break with academic fictions 23.

Manet constructs Olympia as a contract of vision. The nude’s cool, planar lighting, sharp contours, and frontal composition reject the atmospheric softness of academic Venuses; instead of yielding, her left hand clamps down, a visible refusal that conditions access on terms outside the picture 13. Her eyes meet ours without coquetry, making the viewer’s desire and social position part of the work’s content. The black ribbon choker, orchid, bracelet, and the single slipper dangling from her foot signal commodity luxury, not mythic timelessness; they anchor the woman to the marketplace of Second Empire Paris 17. The bouquet—presented by her maid—reads as a client’s offering and thus as evidence of exchange; unlike Titian’s potted myrtle of fidelity, these are cut flowers, already dying, a sign of transience and transaction rather than promise 13. At the bed’s edge, the taut black cat replaces the faithful dog of the classical nude, pivoting the scene from domesticated virtue to nocturnal independence, a modern emblem whose jittery silhouette mirrors the painting’s refusal of idealization 13. In Olympia, the nude is not a fantasy to be consumed but a social actor who prices the encounter. The composition does not create depth in which to lose oneself; it compresses space, hardens edges, and pushes the figure forward, so that the act of looking is both recognized and resisted. This is why contemporaries found the picture scandalous at the 1865 Salon and why Zola defended it as truth-telling modern art: Manet replaced allegory with a blunt reckoning of sex, money, and spectatorship 18. The scandal was not simply nudity but the painting’s acknowledgment of exchange—and the shameless clarity with which Olympia sees the viewer seeing her 3. Equally constitutive is the painting’s racial and labor politics. Recent scholarship identifies the maid as Laure and insists the picture be read as a double portrait: Olympia’s pose and power are staged with and against Laure’s presence, whose work—bearing flowers, mediating gifts, occupying the darker right half—makes the transaction possible and visible 56. Laure’s profile and attentive look introduce another line of sight that complicates the usual one-way traffic of the male gaze; she sees the exchange, and her labor forms the hinge between client and courtesan. The pink dress, white headscarf, and the enveloping green drapery situate her within a network of colonial commodities—textiles, flowers, and the “Oriental” shawl with its tactile fringe—linking Parisian pleasure to global trade 7. By placing a Black working woman at the heart of the scene, Manet ties modern desire to empire and wage labor, exposing how femininity, race, and class are co-constructed in the boudoir 56. This reframing does not soften Olympia’s autonomy; it specifies it. Her control over her body and image exists within, and depends upon, structures of service, money, and spectacle that Laure’s presence materializes. That is why Olympia is important: it inaugurates a modernist language—flatness, abrupt contrasts, frontal address—not as formal experiment alone, but as a means to think power, commodity, and difference. In turning the viewer into a participant and witness to these linked economies, Manet invents a new social function for painting: to scrutinize modern life rather than idealize it 2345.Citations

- Musée d’Orsay, Olympia (object record)

- The Met Museum, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (Manet overview)

- T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life (Princeton UP, 1984/1999)

- Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon (Routledge, 1999)

- Denise Murrell, Posing Modernity (Yale UP/A&AePortal, 2018/2019)

- Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, “Still Thinking about Olympia’s Maid,” The Art Bulletin 97, no. 4 (2015)

- Therese Dolan, “Fringe Benefits: Manet’s Olympia and Her Shawl,” The Art Bulletin 97, no. 4 (2015)

- Émile Zola, Édouard Manet (1867 pamphlet), BnF Gallica

- Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid” (1992; widely anthologized)

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about Olympia

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Reception History

Source: Musée d’Orsay; T.J. Clark; Denise Murrell; Darcy Grigsby; Émile Zola

Historical Context

Source: Musée d’Orsay; Émile Zola; The Met Museum

Formal Analysis

Source: T.J. Clark; Musée d’Orsay

Social Commentary

Source: Denise Murrell; Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby; Therese Dolan

Symbolic Reading

Source: Musée d’Orsay; T.J. Clark; Therese Dolan

Psychological Interpretation

Source: Griselda Pollock; Lorraine O’Grady

Related Themes

About Édouard Manet

More by Édouard Manet

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

Édouard Manet (1882)

Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère stages a face-to-face encounter with modern Paris, where <strong>commerce</strong>, <strong>spectacle</strong>, and <strong>alienation</strong> converge. A composed barmaid fronts a marble counter loaded with branded bottles, flowers, and a brimming bowl of oranges, while a disjunctive <strong>mirror</strong> unravels stable viewing and certainty <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Luncheon on the Grass

Édouard Manet (1863)

Luncheon on the Grass stages a confrontation between <strong>modern Parisian leisure</strong> and <strong>classical precedent</strong>. A nude woman meets our gaze beside two clothed men, while a distant bather and an overturned picnic puncture naturalistic illusion. Manet’s scale and flat, studio-like light convert a park picnic into a manifesto of <strong>modern painting</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Railway

Édouard Manet (1873)

Manet’s The Railway is a charged tableau of <strong>modern life</strong>: a composed woman confronts us while a child, bright in <strong>white and blue</strong>, peers through the iron fence toward a cloud of <strong>steam</strong>. The image turns a casual pause at the Gare Saint‑Lazare into a meditation on <strong>spectatorship, separation, and change</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.