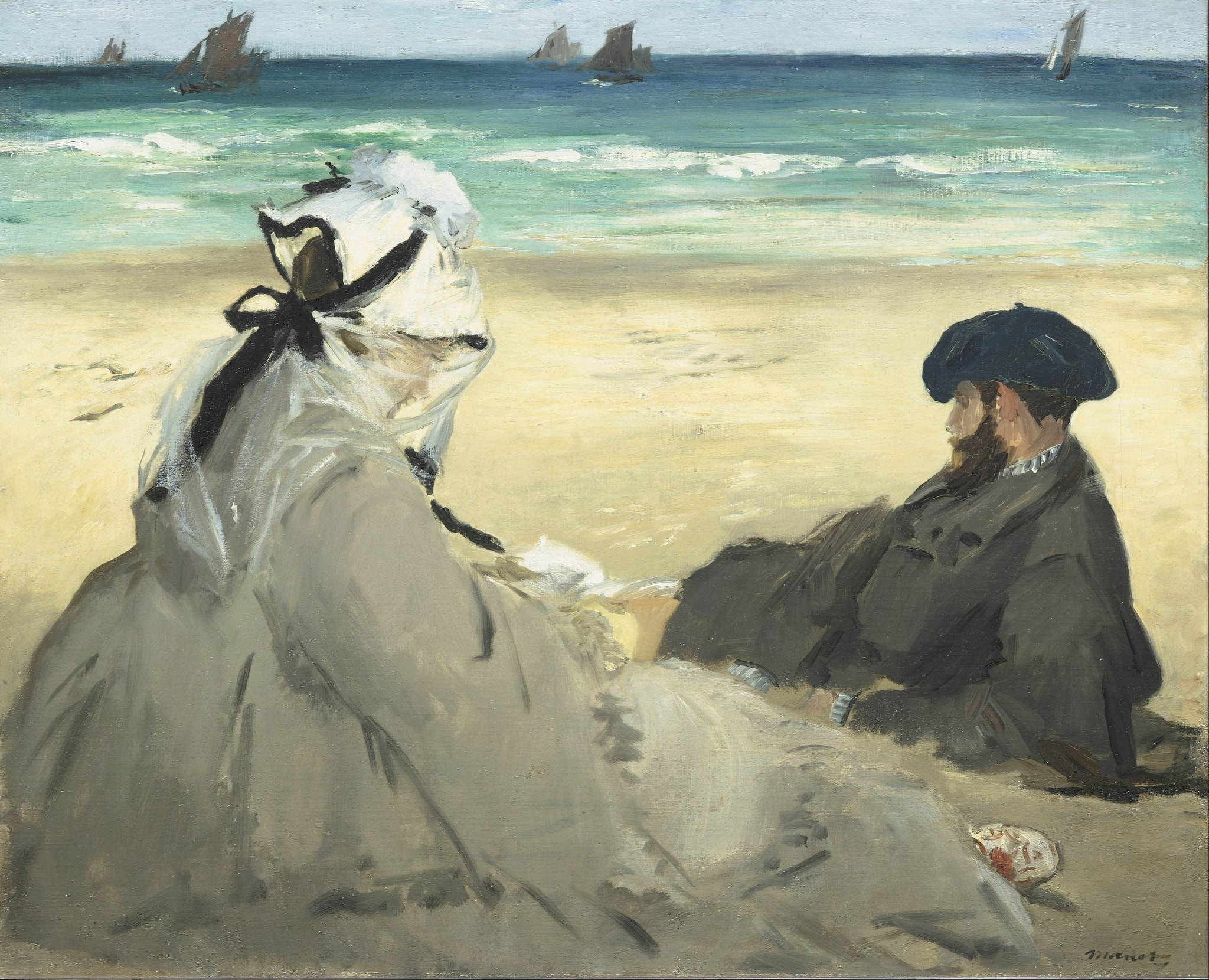

On the Beach

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1873

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 60 x 73.5 cm

- Location

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about On the Beach

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Formal Analysis — Japonisme as Spatial Strategy

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Timeline of Art History; Manet 1832–1883)

Historical Context — Leisure, Rail, and Privacy-in-Public

Source: Robert L. Herbert (Yale A&AePortal); The Met (Timeline of Art History); Art Institute of Chicago (Manet and the Sea)

Medium Reflexivity — Sand, Index, and the ‘Made There’ Look

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Manet 1832–1883)

Psychological Interpretation — Adjacent Solitudes

Source: Musée d’Orsay; Robert L. Herbert (Yale A&AePortal)

Symbolic Reading — The Rhetoric of Black

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Manet 1832–1883)

Related Themes

About Édouard Manet

More by Édouard Manet

Woman Reading

Édouard Manet (1880–82)

Manet’s Woman Reading distills a fleeting act into an emblem of <strong>modern self-possession</strong>: a bundled figure raises a journal-on-a-stick, her luminous profile set against a brisk mosaic of greens and reds. With quick, loaded strokes and a deliberately cropped <strong>beer glass</strong> and paper, Manet turns perception itself into subject—asserting the drama of a private mind within a public café world <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Jeanne (Spring)

Édouard Manet (1881)

Édouard Manet’s Jeanne (Spring) fuses a time-honored allegory with <strong>modern Parisian fashion</strong>: a crisp profile beneath a cream parasol, set against <strong>luminous, leafy greens</strong>. Manet turns couture—hat, glove, parasol—into the language of <strong>renewal and youth</strong>, making spring feel both perennial and up-to-the-minute <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Plum Brandy

Édouard Manet (ca. 1877)

Manet’s Plum Brandy crystallizes a modern pause—an urban <strong>interval of suspended action</strong>—through the idle tilt of a woman’s head, an <strong>unlit cigarette</strong>, and a glass cradling a <strong>plum in amber liquor</strong>. The boxed-in space—marble table, red banquette, and decorative grille—turns a café moment into a stage for <strong>solitude within public life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Music in the Tuileries

Édouard Manet (1862)

Édouard Manet’s Music in the Tuileries turns a Sunday concert into a manifesto of <strong>modern life</strong>: a frieze of top hats, crinolines, and iron chairs flickering beneath <strong>toxic green</strong> foliage. Instead of a hero or center, the painting disperses attention across a restless crowd, making <strong>looking itself</strong> the drama of the scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets

Édouard Manet (1872)

Édouard Manet’s Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets is a close, modern portrait built as a <strong>symphony in black</strong> punctuated by a tiny violet knot. Side‑light chisels the face from a cool, silvery ground while hat, scarf, and coat merge into one dark silhouette, and the eyes are painted strikingly <strong>black</strong> for effect <sup>[1]</sup>. The single touch of violets introduces a discreet, coded <strong>tenderness</strong> within the portrait’s refined restraint <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.