Human vs. nature

Featured Artworks

Boating

Claude Monet (1887)

Monet’s Boating crystallizes modern leisure as a drama of perception, setting a slim skiff and two pale dresses against a field of dark, mobile water. Bold cropping, a thrusting oar, and the complementary flash of hull and foliage convert a quiet outing into an experiment in <strong>modern vision</strong> and the <strong>materiality of water</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive)

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive) (1875) turns a suburban winter platform into a study of <strong>modernity absorbed by atmosphere</strong>. The engine’s twin yellow headlights and a smear of red push through a world of greys and violets as steam fuses with the low sky, while the right-hand fence and bare trees drill depth and cadence into the scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Monet fixes not an object but a <strong>moment of perception</strong>, where industry seems to dematerialize into weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Water Lilies

Claude Monet (1899)

<strong>Water Lilies</strong> centers on an arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> suspended over a pond where lilies and rippling reflections fuse into a single, vibrating surface. Monet turns the scene into a study of <strong>perception-in-flux</strong>, letting water, foliage, and light dissolve hard edges into atmospheric continuity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Water Lily Pond

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond transforms a designed garden into a theater of <strong>perception and reflection</strong>. The pale, arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> hovers over a surface where lilies, reeds, and mirrored willow fronds dissolve boundaries between water and sky, proposing <strong>seeing itself</strong> as the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect

Claude Monet (1903 (begun 1900))

Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect renders London as a <strong>lilac-blue atmosphere</strong> where form yields to light. The bridge’s stone arches persist as anchors, yet the span dissolves into mist while <strong>flecks of lemon and ember</strong> signal modern traffic crossing a city made weightless <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Vertical hints of chimneys haunt the distance, binding industry to beauty as the Thames shimmers with the same notes as the sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Grand Canal

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s The Grand Canal turns Venice into <strong>pure atmosphere</strong>: the domes of Santa Maria della Salute waver at right while a regiment of <strong>pali</strong> stands at left, their verticals reverberating in the water. The scene asserts <strong>light over architecture</strong>, transforming stone into memory and time into color <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

Caspar David Friedrich (ca. 1817)

A solitary figure stands on a jagged crag above a churning <strong>sea of fog</strong>, his back turned in the classic <strong>Rückenfigur</strong> pose. Caspar David Friedrich transforms the landscape into an inner stage where <strong>awe, uncertainty, and resolve</strong> meet at the edge of perception <sup>[3]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Skiff (La Yole)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1875)

In The Skiff (La Yole), Pierre-Auguste Renoir stages a moment of modern leisure on a broad, vibrating river, where a slender, <strong>orange skiff</strong> cuts across a field of <strong>cool blues</strong>. Two women ride diagonally through the shimmer; an <strong>oar’s sweep</strong> spins a vortex of color as a sailboat, villa, and distant bridge settle the scene on the Seine’s suburban edge <sup>[1]</sup>. Renoir turns motion and light into a single sensation, using a high‑chroma, complementary palette to fuse human pastime with nature’s flux <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

On the Beach

Édouard Manet (1873)

On the Beach captures a paused interval of modern leisure: two fashionably dressed figures sit on pale sand before a <strong>banded, high-horizon sea</strong>. Manet’s <strong>economical brushwork</strong>, restricted greys and blacks, and radical cropping stage a scene of absorption and wind‑tossed motion that feels both intimate and detached <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Cliff Walk at Pourville

Claude Monet (1882)

Claude Monet’s The Cliff Walk at Pourville renders wind, light, and sea as interlocking forces through <strong>shimmering, broken brushwork</strong>. Two small walkers—one beneath a pink parasol—stand near the <strong>precipitous cliff edge</strong>, their presence measuring the vastness of turquoise water and bright sky dotted with white sails. The scene fuses leisure and the <strong>modern sublime</strong>, making perception itself the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Wheatfield with Crows

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

A panoramic wheatfield splits around a rutted track under a storm-charged sky while black crows rush toward us. Van Gogh drives complementary blues and yellows into collision, fusing <strong>nature’s vitality</strong> with <strong>inner turbulence</strong>.

The Sea of Ice

Caspar David Friedrich (1823–1824)

Caspar David Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice turns nature into a <strong>frozen architecture</strong> that crushes a ship and, with it, human pretension. The painting stages the <strong>Romantic sublime</strong> as both awe and negation, replacing heroic conquest with the stark finality of ice and silence <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Rain, Steam and Speed

J. M. W. Turner (1844)

In Rain, Steam and Speed, J. M. W. Turner fuses weather and industry into a single onrushing vision, as a dark locomotive thrusts along the diagonal of Brunel’s Maidenhead Railway Bridge through veils of rain and light. The blurred fields, river, and town dissolve into a charged atmosphere where <strong>rain</strong>, <strong>steam</strong>, and <strong>speed</strong> become the true subjects. Counter-motifs—a small boat beneath pale arches and a near-invisible hare ahead of the train—stage a drama between pre‑industrial life and modern velocity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Charing Cross Bridge

Claude Monet (1901)

In Charing Cross Bridge, Claude Monet turns London into <strong>atmosphere</strong> itself: the bridge flattens into a cool, horizontal band while mauves, lavenders, and pearly grays veil the city. Spirals of <strong>pink steam</strong> and pockets of pale <strong>blue</strong> read as trains, lamps, or smoke transfigured by weather, so place becomes <strong>sensation</strong> rather than structure.

The Umbrellas

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1881–86)

A sudden shower turns a Paris street into a lattice of <strong>slate‑blue umbrellas</strong>, knitting strangers into a single moving frieze. A bareheaded young woman with a <strong>bandbox</strong> strides forward while a bourgeois mother and children cluster at right, their <strong>hoop</strong> echoing the umbrellas’ arcs <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Basket of Apples

Paul Cézanne (c. 1893)

Paul Cézanne’s The Basket of Apples stages a quiet drama of <strong>balance and perception</strong>. A tilted basket spills apples across a <strong>rumpled white cloth</strong> toward a <strong>dark vertical bottle</strong> and a plate of <strong>biscuits</strong>, while the tabletop’s edges refuse to align—an intentional play of <strong>multiple viewpoints</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Still Life with Apples and Oranges

Paul Cézanne (c. 1899)

Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples and Oranges builds a quietly monumental world from domestic things. A tilting table, a heaped white compote, a flowered jug, and cascading cloths turn fruit into <strong>durable forms</strong> stabilized by <strong>color relationships</strong> rather than single‑point perspective <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The result is a still life that feels both solid and subtly <strong>unstable</strong>, a meditation on how we construct vision.

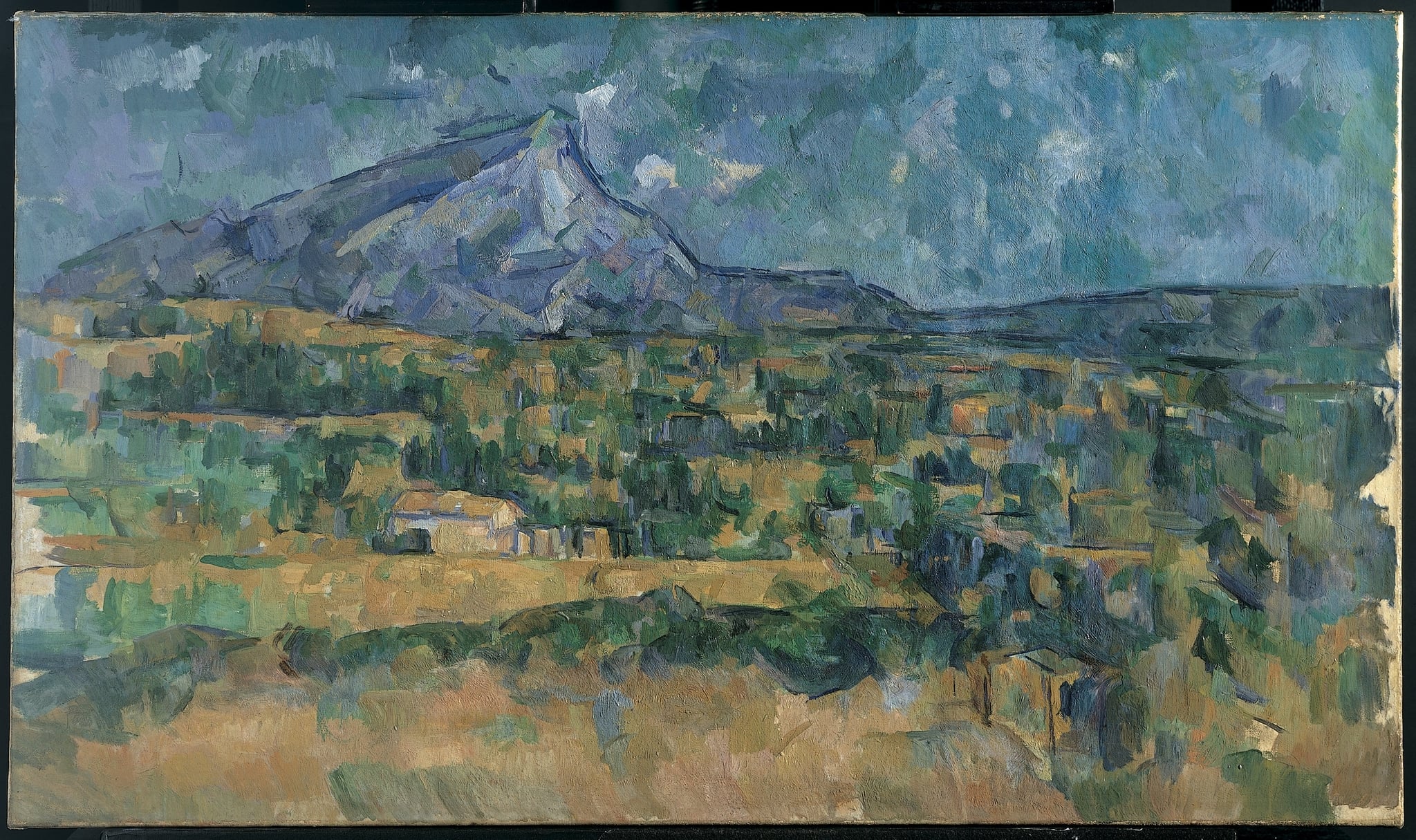

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne (1902–1906)

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire renders the Provençal massif as a constructed order of <strong>planes and color</strong>, not a fleeting impression. Cool blues and violets articulate the mountain’s facets, while <strong>ochres and greens</strong> laminate the fields and blocky houses, binding atmosphere and form into a single structure <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Storm on the Sea of Galilee

Rembrandt van Rijn (1633)

Rembrandt van Rijn’s The Storm on the Sea of Galilee stages a clash of <strong>human panic</strong> and <strong>divine composure</strong> at the instant before the miracle. A torn mainsail whips across a steeply tilted boat as terrified disciples scramble, while a <strong>serenely lit Christ</strong> anchors a pocket of calm—an image of faith holding within chaos <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. It is Rembrandt’s only painted seascape, intensifying its dramatic singularity in his oeuvre <sup>[2]</sup>.

Flood at Port-Marly

Alfred Sisley (1876)

In Flood at Port-Marly, Alfred Sisley turns a flooded street into a reflective stage where <strong>human order</strong> and <strong>natural flux</strong> converge. The aligned, leafless trees function like measuring rods against the water, while flat-bottomed boats replace carriages at the curb. With cool, silvery strokes and a cloud-laden sky, Sisley asserts that the scene’s true drama is <strong>atmosphere</strong> and <strong>adaptation</strong>, not catastrophe <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Red Boats, Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Red Boats, Argenteuil crystallizes a luminous afternoon on the Seine, where two <strong>vermilion hulls</strong> anchor a scene of leisure and light. The tremoring <strong>reflections</strong> and vertical <strong>masts/poplars</strong> weave nature and modern recreation into a single atmospheric field <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Terrace at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet (1867)

Claude Monet’s The Terrace at Sainte-Adresse stages a sunlit garden against the Channel, where <strong>bourgeois leisure</strong> unfolds between two wind-whipped flags and a horizon shared by <strong>sail and steam</strong>. Bright flowers, wicker chairs, and a white parasol form an ordered foreground, while the busy harbor and snapping tricolor project a confident, modern nation. The banded design—garden, sea, sky—reveals Monet’s early <strong>Japonisme</strong> and his drive to fuse fleeting light with a consciously structured composition <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train

Claude Monet (1877)

Claude Monet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train plunges viewers into a <strong>vapor-filled nave of iron and glass</strong>, where billowing steam, hot lamps, and converging rails forge a drama of industrial modernity. The right-hand locomotive, its red buffer beam glowing, materializes out of a <strong>blue-gray atmospheric envelope</strong>, turning motion and time into visible substance <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Poplars on the Epte

Claude Monet (1891)

Claude Monet’s Poplars on the Epte turns a modest river bend into a meditation on <strong>time, light, and perception</strong>. Upright trunks register as steady <strong>vertical chords</strong>, while their broken, shimmering reflections loosen form into <strong>pure sensation</strong>. The image stages a tension between <strong>order and flux</strong> that anchors the series within Impressionism’s core aims <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

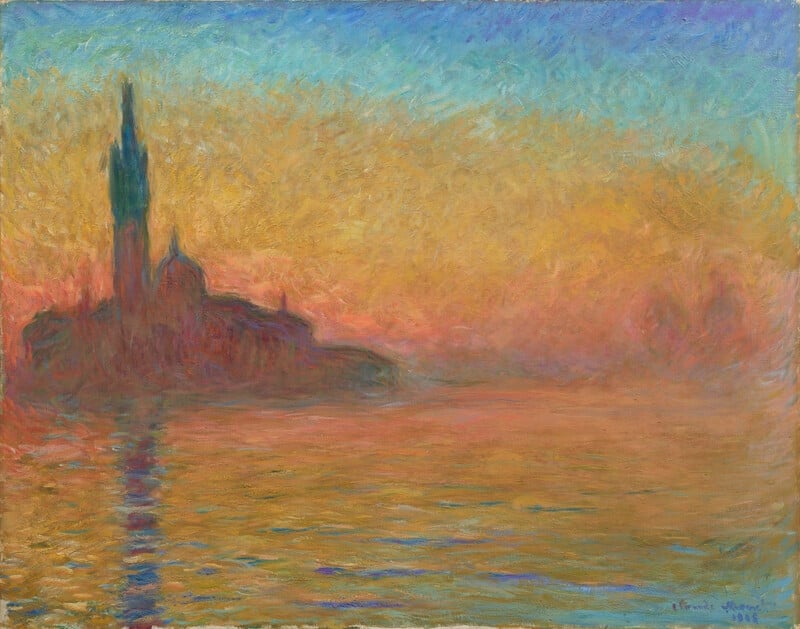

San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight turns Venice into a <strong>luminous threshold</strong> where stone, air, and water merge. The dark, melting silhouette of the church and its vertical reflection anchor a field of <strong>apricot–rose–violet</strong> light that drifts into cool turquoise, making permanence feel provisional <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet’s subject is not the monument, but the <strong>enveloppe</strong> of atmosphere that momentarily creates it <sup>[4]</sup>.

The Creation of Adam

Michelangelo (c.1511–1512)

Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam crystallizes the instant before life is conferred, staging a charged interval between two nearly touching hands. The fresco turns Genesis into a study of <strong>imago Dei</strong>, bodily perfection, and the threshold between inert earth and <strong>active spirit</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Hokusai (ca. 1830–32)

The Great Wave off Kanagawa distills a universal drama: fragile laboring boats face a <strong>towering breaker</strong> while <strong>Mount Fuji</strong> sits small yet immovable. Hokusai wields <strong>Prussian blue</strong> to sculpt depth and cold inevitability, fusing ukiyo‑e elegance with Western perspective to stage nature’s power against human resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog

Caspar David Friedrich (ca. 1817)

Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog distills the Romantic encounter with nature into a single <strong>Rückenfigur</strong> poised on jagged rock above a rolling <strong>sea of mist</strong>. The cool, receding vista and the figure’s still stance convert landscape into an <strong>inner drama of contemplation</strong> and the <strong>sublime</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Sleeping Gypsy

Henri Rousseau (1897)

Under a cold moon, a traveler sleeps in a striped robe as a lion pauses to sniff, not strike—an image of <strong>danger held in suspension</strong> and <strong>imagination as protection</strong>. Rousseau’s polished surfaces, flattened distance, and toy-like clarity turn the desert into a <strong>dream stage</strong> where art (the mandolin) and life (the water jar) keep silent vigil <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Raft of the Medusa

Theodore Gericault (1818–1819)

The Raft of the Medusa stages a modern catastrophe as epic tragedy, pivoting from corpses to a surge of <strong>collective hope</strong>. The diagonal mast, torn sail, and a Black figure waving a cloth toward a tiny ship compress the moment when despair turns to <strong>precarious rescue</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man

Peter Paul Rubens (c. 1615)

<strong>The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man</strong> stages the instant Eve passes the forbidden fruit to Adam as the serpent coils above and a teeming paradise encircles them. The panel fuses Peter Paul Rubens’s dramatic nudes with Jan Brueghel the Elder’s encyclopedic fauna and flora, turning Eden into a lush theatre of temptation and consequence <sup>[1]</sup>. Light isolates Eve’s raised arm and golden hair while predators stir at the margins, signaling paradise in the act of unraveling.

The Manneporte near Étretat

Claude Monet (1886)

Monet’s The Manneporte near Étretat turns the colossal sea arch into a <strong>threshold of light</strong>: rock, sea, and air interlock as shifting color rather than fixed form. Dense lilac–ochre strokes make the cliff feel massive yet <strong>dematerialized</strong> by illumination, while the arch’s opening stages a quiet, glimmering horizon <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.