Loneliness & isolation

Featured Artworks

The Red Studio

Henri Matisse (1911)

Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911) saturates the artist’s workspace in a continuous field of <strong>Venetian red</strong>, collapsing walls, floor, and furniture into a single chromatic plane. Objects and architecture appear as <strong>mustard-yellow reserve lines</strong> that read like drawing, while Matisse’s own paintings and sculptures retain full color, asserting art’s primacy within the room <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The result is a studio that feels like a <strong>mental map</strong> rather than a literal interior.

After the Luncheon

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879)

After the Luncheon crystallizes a <strong>suspended instant</strong> of Parisian leisure: coffee finished, glasses dappled with light, and a cigarette just being lit. Renoir’s <strong>shimmering brushwork</strong> and the trellised spring foliage turn the scene into a tapestry of conviviality where time briefly pauses.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

On the Beach

Édouard Manet (1873)

On the Beach captures a paused interval of modern leisure: two fashionably dressed figures sit on pale sand before a <strong>banded, high-horizon sea</strong>. Manet’s <strong>economical brushwork</strong>, restricted greys and blacks, and radical cropping stage a scene of absorption and wind‑tossed motion that feels both intimate and detached <sup>[1]</sup>.

Plum Brandy

Édouard Manet (ca. 1877)

Manet’s Plum Brandy crystallizes a modern pause—an urban <strong>interval of suspended action</strong>—through the idle tilt of a woman’s head, an <strong>unlit cigarette</strong>, and a glass cradling a <strong>plum in amber liquor</strong>. The boxed-in space—marble table, red banquette, and decorative grille—turns a café moment into a stage for <strong>solitude within public life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Wheatfield with Crows

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

A panoramic wheatfield splits around a rutted track under a storm-charged sky while black crows rush toward us. Van Gogh drives complementary blues and yellows into collision, fusing <strong>nature’s vitality</strong> with <strong>inner turbulence</strong>.

Place de la Concorde

Edgar Degas (1875)

Degas’s Place de la Concorde turns a famous Paris square into a study of <strong>modern isolation</strong> and <strong>instantaneous vision</strong>. Figures stride past one another without contact, their bodies abruptly <strong>cropped</strong> and adrift in a wide, airless plaza—an urban stage where elegance masks estrangement <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

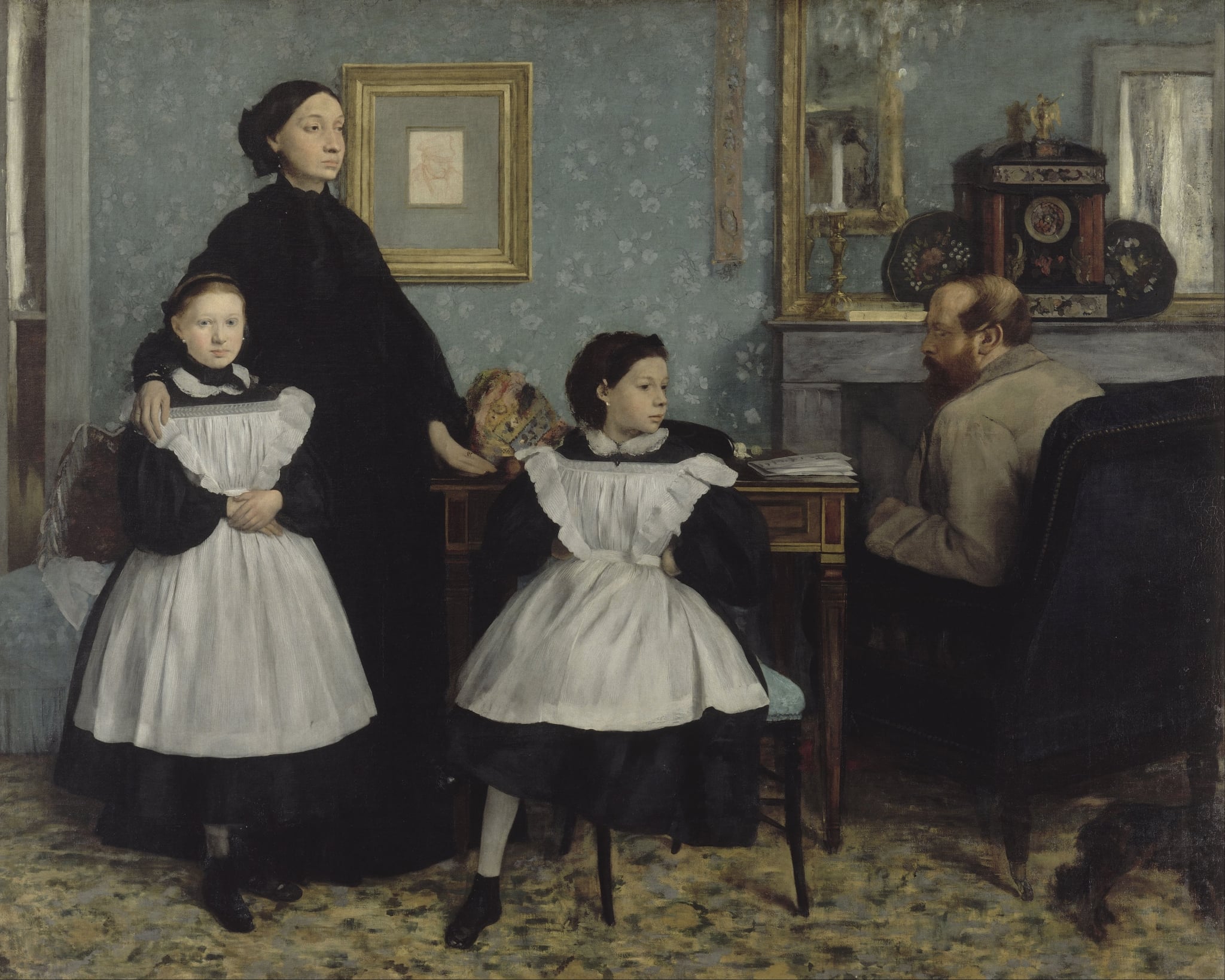

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Star

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1878)

Edgar Degas’s The Star shows a prima ballerina caught at the crest of a pose, her tutu a <strong>vaporous flare</strong> against a <strong>murky, tilted stage</strong>. Diagonal floorboards rush beneath her single pointe, while pale, ghostlike dancers linger in the wings, turning triumph into a scene of <strong>radiant isolation</strong> <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

At the Moulin Rouge

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892–1895)

At the Moulin Rouge plunges us into the churn of Paris nightlife, staging a crowded room where spectacle and fatigue coexist. A diagonal banister and abrupt croppings create <strong>off‑kilter immediacy</strong>, while harsh artificial light turns faces <strong>masklike</strong> and cool. Mirrors multiply the crowd, amplifying a mood of allure tinged with <strong>urban alienation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Camille Monet on a Garden Bench

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Camille Monet on a Garden Bench (1873) stages an intimate pause where <strong>light, grief, and modern leisure</strong> intersect. Camille, shaded and withdrawn, holds a letter while a <strong>top‑hatted neighbor</strong> hovers; a bright bank of <strong>red geraniums</strong> and a strolling woman with a parasol ignite the distance <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet converts a domestic garden into a scene about <strong>psychological distance</strong> amid fleeting sunlight.

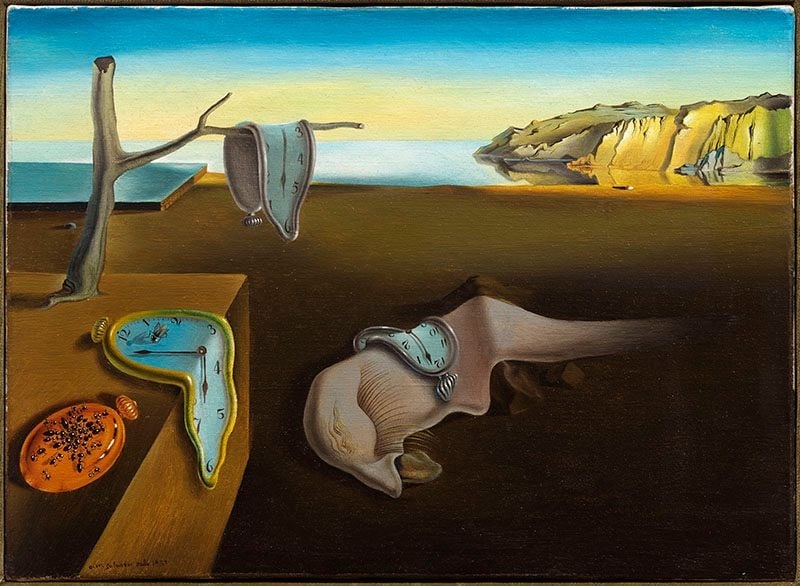

The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dali (1931)

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory turns clock time into <strong>soft, malleable matter</strong>, staging a dream in which chronology buckles and the self dissolves. Four pocket watches droop across a barren platform, a dead branch, and a lash‑eyed biomorph, while ants overrun a hard, closed watch—a sign of <strong>decay</strong> and the futility of mechanical order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper (1942)

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks turns a corner diner into a sealed stage where <strong>fluorescent light</strong> and <strong>curved glass</strong> hold four figures in suspended time. The empty streets and the “PHILLIES” cigar sign sharpen the sense of <strong>urban solitude</strong> while hinting at wartime vigilance. The result is a cool, lucid image of modern life: illuminated, open to view, and emotionally out of reach.

The Lovers

Rene Magritte (1928)

René Magritte’s The Lovers turns a kiss into an emblem of <strong>desire obstructed</strong>: two figures—she in red, he in a dark suit—press together while their heads are swathed in <strong>white cloth</strong>. Within a cool blue‑grey interior bounded by crown molding and a rust-red wall, intimacy becomes an image of <strong>opacity</strong> rather than revelation <sup>[1]</sup>.