Bathers by Paul Cézanne: Geometry of the Modern Nude

by Paul Cézanne

Fast Facts

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about Bathers by Paul Cézanne: Geometry of the Modern Nude

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Related Themes

About Paul Cézanne

More by Paul Cézanne

The Card Players by Paul Cézanne | Equilibrium and Form

Paul Cézanne

In The Card Players, Paul Cézanne turns a rural café game into a study of <strong>equilibrium</strong> and <strong>monumentality</strong>. Two hated peasants lean inward across an orange-brown table while a dark bottle stands upright between them, acting as a calm, vertical <strong>axis</strong> that stabilizes their mirrored focus <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

The Basket of Apples

Paul Cézanne (c. 1893)

Paul Cézanne’s The Basket of Apples stages a quiet drama of <strong>balance and perception</strong>. A tilted basket spills apples across a <strong>rumpled white cloth</strong> toward a <strong>dark vertical bottle</strong> and a plate of <strong>biscuits</strong>, while the tabletop’s edges refuse to align—an intentional play of <strong>multiple viewpoints</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Still Life with Apples and Oranges

Paul Cézanne (c. 1899)

Paul Cézanne’s Still Life with Apples and Oranges builds a quietly monumental world from domestic things. A tilting table, a heaped white compote, a flowered jug, and cascading cloths turn fruit into <strong>durable forms</strong> stabilized by <strong>color relationships</strong> rather than single‑point perspective <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The result is a still life that feels both solid and subtly <strong>unstable</strong>, a meditation on how we construct vision.

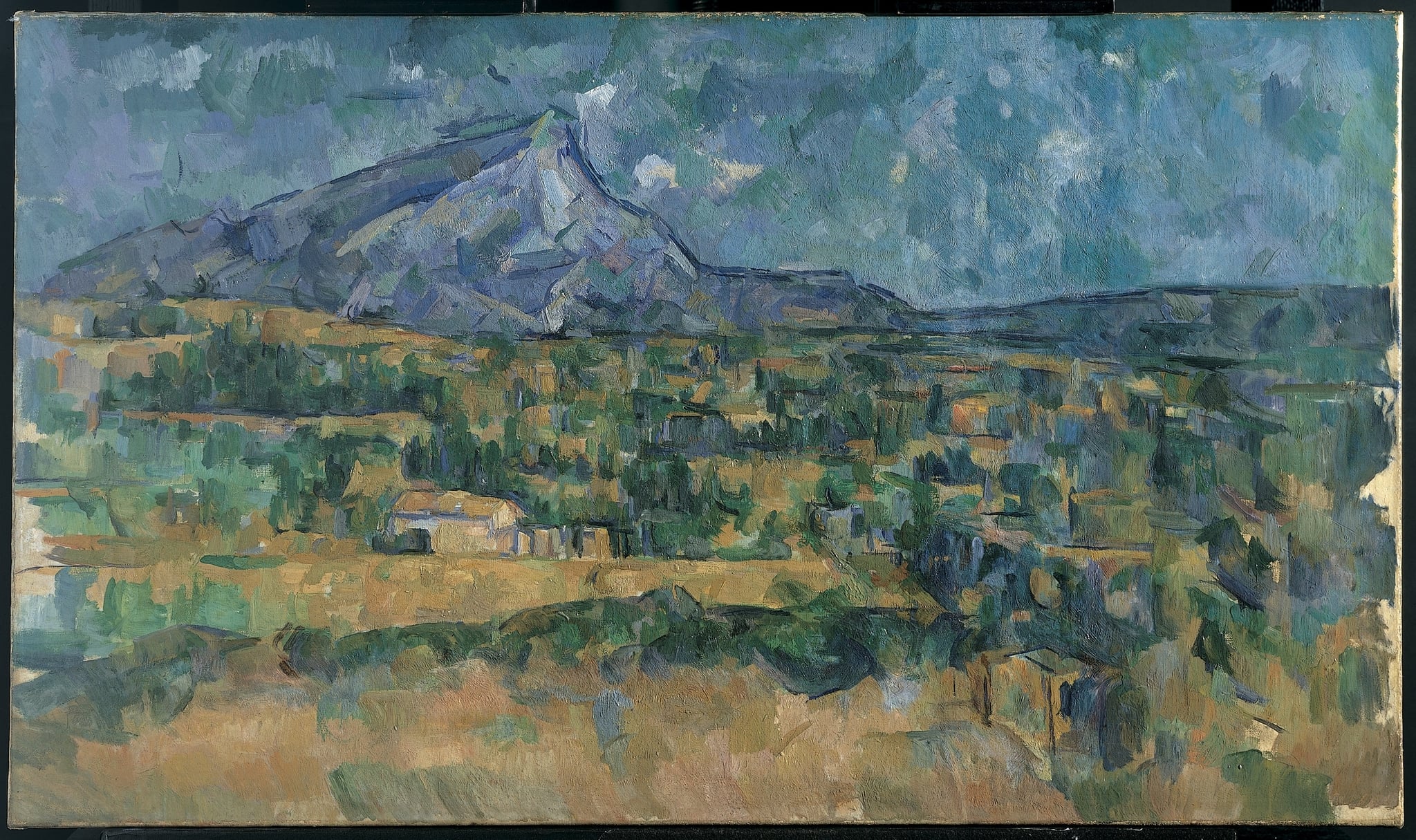

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne (1902–1906)

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire renders the Provençal massif as a constructed order of <strong>planes and color</strong>, not a fleeting impression. Cool blues and violets articulate the mountain’s facets, while <strong>ochres and greens</strong> laminate the fields and blocky houses, binding atmosphere and form into a single structure <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair

Paul Cézanne (about 1877)

Paul Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (about 1877) turns a domestic sit into a study of <strong>color-built structure</strong> and <strong>compressed space</strong>. Cool blue-greens of dress and skin lock against the saturated <strong>crimson armchair</strong>, converting likeness into an inquiry about how painting makes stability visible <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.