The Cliff, Etretat

by Claude Monet

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1882–1883

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 60.5 × 81.8 cm

- Location

- North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Cliff, Etretat

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Social-Historical Context: Tourism, Spectacle, and the ‘Grand View’

Source: Robert L. Herbert; North Carolina Museum of Art

Seriality as Meaning: Repetition, Control, and Loss

Source: Steven Z. Levine; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Optical Forensics: Dating a Sunset, Testing Impressionism

Source: Sky & Telescope; North Carolina Museum of Art (Learn)

Formal Analysis: Silhouette, Facture, and Edge Hierarchies

Source: NCMA (Learn); The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Labor and Risk: Working the Edge of Weather and Tide

Source: NCMA (Learn); Clark Art Institute

Icon and Threshold: The ‘Gate’ Recast

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Related Themes

About Claude Monet

More by Claude Monet

La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume)

Claude Monet (1876)

Claude Monet’s La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume) (1876) stages a witty confrontation between <strong>Parisian modernity</strong> and the fashion for <strong>Japonisme</strong>. A fair-skinned model in a blazing red uchikake preens before a wall tiled with uchiwa fans, lifting a <strong>tricolor</strong> hand fan that asserts Frenchness amid the imported decor. The painting turns costume, props, and gaze into a performance about <strong>desire, display, and identity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Boating

Claude Monet (1887)

Monet’s Boating crystallizes modern leisure as a drama of perception, setting a slim skiff and two pale dresses against a field of dark, mobile water. Bold cropping, a thrusting oar, and the complementary flash of hull and foliage convert a quiet outing into an experiment in <strong>modern vision</strong> and the <strong>materiality of water</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Thames below Westminster

Claude Monet (about 1871)

Claude Monet’s The Thames below Westminster turns London into <strong>light-made architecture</strong>, where Parliament’s mass dissolves into mist and the river shivers with <strong>industrial motion</strong>. Tugboats, a timber jetty with workers, and the rebuilt Westminster Bridge assert a modern city whose power is felt through atmosphere more than outline <sup>[1]</sup>.

Haystacks Series by Claude Monet | Light, Time & Atmosphere

Claude Monet

Claude Monet’s <strong>Haystacks Series</strong> transforms a routine rural subject into an inquiry into <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunset view, the stacks swell at the left while the sun burns through the gap, making the field shimmer with <strong>apricot, lilac, and blue</strong> vibrations.

Women in the Garden

Claude Monet (1866–1867)

Claude Monet’s Women in the Garden choreographs four figures in a sunlit bower to test how <strong>white dresses</strong> register <strong>dappled light</strong> and shadow. The path, parasol, and clipped flowers frame a modern ritual of leisure while turning fashion into an instrument of <strong>perception</strong>. The scene reads less as portraiture than as a manifesto for painting the <strong>momentary</strong> outdoors <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

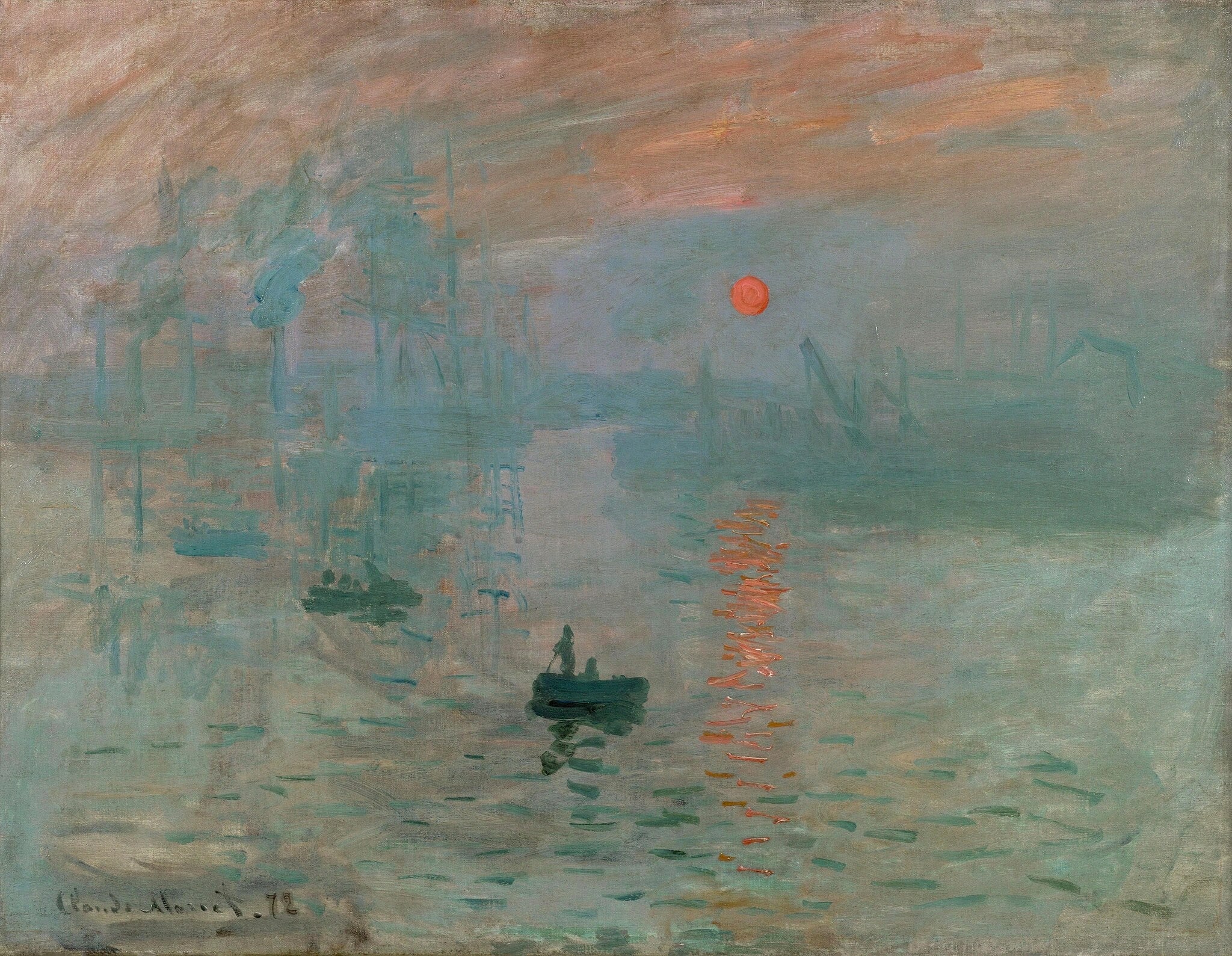

Impression, Sunrise

Claude Monet (1872)

In Impression, Sunrise, Claude Monet turns Le Havre’s fog-bound harbor into an experiment in <strong>immediacy</strong> and <strong>modernity</strong>. Cool blue-greens dissolve cranes, masts, and smoke, while a small skiff cuts the water beneath a blazing, <strong>equiluminant</strong> orange sun whose vertical reflection stitches the scene together <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The effect is a poised dawn where industry meets nature, a quiet <strong>awakening</strong> rendered through light rather than line.