The Great Masturbator

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1929

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 110 × 150 cm

- Location

- Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Great Masturbator

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Formal Analysis: Hard/Soft Dialectics and the Precision of Panic

Source: Fèlix Fanés (Yale University Press); Museo Reina Sofía; Dalí Museum

Place & Geology: Cadaqués as Psychic Engine

Source: Museo Reina Sofía; Fèlix Fanés

Psychoanalytic Iconography: Predation, Putrefaction, and Injury

Source: The Met; Gala‑Salvador Dalí Foundation; Dalí Museum

Surrealist Method: Toward the Paranoiac‑Critical Image

Source: Museo Reina Sofía; Britannica; Fèlix Fanés

Purity Against Stain: A Christian Code in a Sexual Crisis

Source: Museo Reina Sofía; Dalí Museum; General Christian iconography

Related Themes

About Salvador Dali

More by Salvador Dali

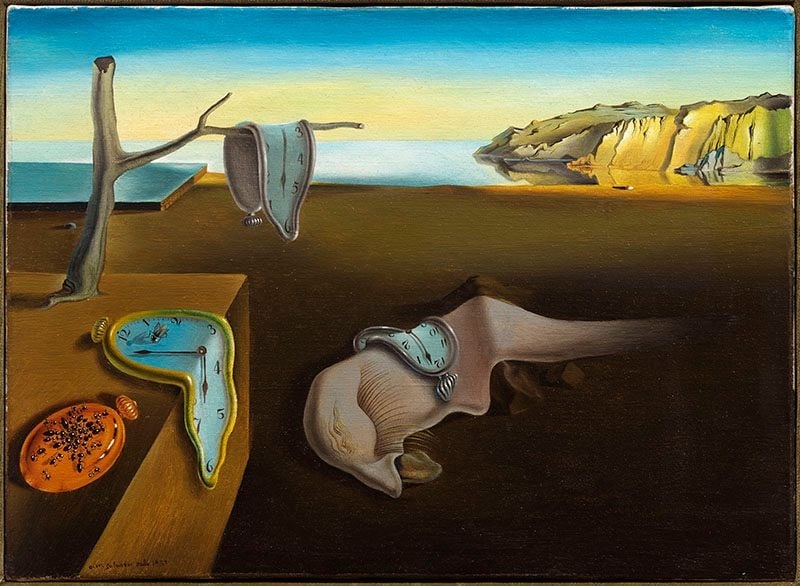

The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dali (1931)

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory turns clock time into <strong>soft, malleable matter</strong>, staging a dream in which chronology buckles and the self dissolves. Four pocket watches droop across a barren platform, a dead branch, and a lash‑eyed biomorph, while ants overrun a hard, closed watch—a sign of <strong>decay</strong> and the futility of mechanical order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Elephants

Salvador Dali (1948)

In The Elephants, Salvador Dali distills a stark paradox of <strong>weight and weightlessness</strong>: gaunt elephants tiptoe on <strong>stilt-thin legs</strong> while bearing stone <strong>obelisks</strong>. The blazing red-orange sky and tiny human figures compress ambition into a vision of <strong>precarious power</strong> and time stretched thin <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Swans Reflecting Elephants

Salvador Dali (1937)

Swans Reflecting Elephants stages a calm Catalan lagoon where three swans and a thicket of bare trees flip into monumental <strong>elephants</strong> in the mirror of water. Salvador Dali crystallizes his <strong>paranoiac-critical</strong> method: a meticulously painted illusion that makes perception generate its own doubles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work locks grace to gravity, surface to depth, turning the lake into a theater of <strong>metamorphosis</strong>.