Power & authority

Featured Artworks

Woman in Black at the Opera

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman in Black at the Opera stages a taut drama of vision and visibility. A woman in <strong>black attire</strong> raises <strong>opera glasses</strong> while a distant man aims his own at her, setting off a chain of looks that makes public leisure a site of <strong>power, agency, and surveillance</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I

Gustav Klimt (1907)

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I stages its sitter as a <strong>secular icon</strong>—a living presence suspended in a field of gold that converts space into <strong>pattern and power</strong>. The naturalistic face and hands emerge from a reliquary-like cascade of eyes, triangles, and tesserae, turning light, ornament, and status into the painting’s true subjects <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Elevation of the Cross

Peter Paul Rubens (1609–1610)

A single, surging diagonal drives The Elevation of the Cross as straining executioners heave the timber while Christ’s pale body becomes the calm, radiant fulcrum. Rubens fuses muscular anatomy, flashing armor, taut ropes, and storm-dark landscape into a Baroque crescendo where <strong>divine light</strong> confronts <strong>human violence</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Thames below Westminster

Claude Monet (about 1871)

Claude Monet’s The Thames below Westminster turns London into <strong>light-made architecture</strong>, where Parliament’s mass dissolves into mist and the river shivers with <strong>industrial motion</strong>. Tugboats, a timber jetty with workers, and the rebuilt Westminster Bridge assert a modern city whose power is felt through atmosphere more than outline <sup>[1]</sup>.

A Woman and a Girl Driving

Mary Cassatt (1881)

Cassatt stages a modern scene of <strong>female control</strong> in motion: a woman grips the reins and whip while a girl beside her mirrors the pose, and a groom seated behind looks away. The cropped horse and diagonal harness thrust the carriage forward, placing viewers inside a public outing in the Bois de Boulogne—an arena where visibility signaled status and autonomy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Young Girls at the Piano

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892)

Renoir’s Young Girls at the Piano turns a quiet lesson into a scene of <strong>attunement</strong> and <strong>bourgeois grace</strong>. Two adolescents—one seated at the keys, the other leaning to guide the score—embody harmony between discipline and delight, rendered in Renoir’s late, <strong>luminous</strong> touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David (1784 (exhibited 1785))

In The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David crystallizes <strong>civic duty over private feeling</strong>: three Roman brothers extend their arms to swear allegiance as their father raises <strong>three swords</strong> at the perspectival center. The painting’s severe geometry, austere architecture, and polarized groups of <strong>rectilinear men</strong> and <strong>curving mourners</strong> stage a manifesto of <strong>Neoclassical virtue</strong> and republican resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive)

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive) (1875) turns a suburban winter platform into a study of <strong>modernity absorbed by atmosphere</strong>. The engine’s twin yellow headlights and a smear of red push through a world of greys and violets as steam fuses with the low sky, while the right-hand fence and bare trees drill depth and cadence into the scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Monet fixes not an object but a <strong>moment of perception</strong>, where industry seems to dematerialize into weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Reading Le Figaro

Mary Cassatt (c. 1878–83)

Mary Cassatt’s Reading Le Figaro turns a quiet parlor into a scene of <strong>intellect</strong> and <strong>modern life</strong>. The inverted masthead, mirrored repetition of the paper, and the sitter’s spectacles make <strong>attention</strong>—not appearance—the true subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Through brisk whites and grays, Cassatt dignifies everyday thought as a modern pictorial theme aligned with <strong>Impressionism</strong> <sup>[2]</sup>.

Pont Neuf Paris

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1872)

In Pont Neuf Paris, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns the oldest bridge in Paris into a stage where <strong>light</strong> and <strong>movement</strong> bind a city back together. From a high perch, he orchestrates crowds, carriages, gas lamps, the rippling Seine, and a fluttering <strong>tricolor</strong> so that everyday bustle reads as civic grace <sup>[1]</sup>.

Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Jacques-Louis David (1801–1805 (series of five versions))

Jacques-Louis David turns a difficult Alpine passage into a <strong>myth of command</strong>: a serene leader on a rearing charger, a <strong>billowing golden cloak</strong>, and names cut into stone that bind the crossing to Hannibal and Charlemagne. The painting manufactures <strong>political legitimacy</strong> by fusing modern uniform and classical gravitas into a single, upward-driving image <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt

Mary Cassatt (1884)

A quiet, domestic tableau becomes a study in <strong>authority tempered by affection</strong>. In Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, Mary Cassatt fuses father and child into a single dark silhouette against a luminous, brushed interior, their shared gaze fixed beyond the frame. The <strong>newspaper</strong>, <strong>linked hands</strong>, and <strong>cropped closeness</strong> transform a routine moment into a symbol of generational continuity and modern attentiveness.

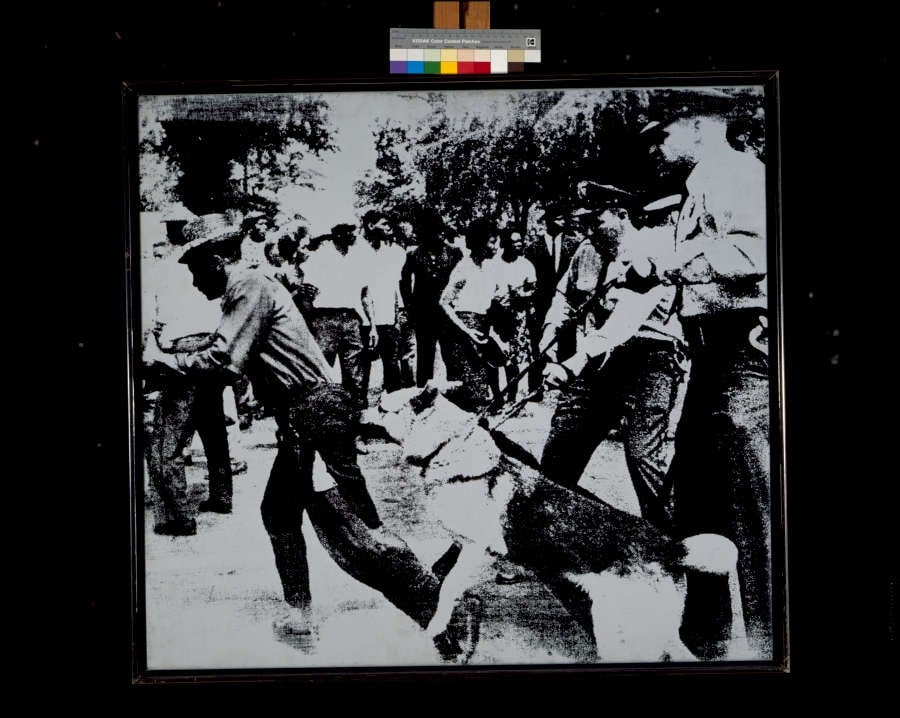

Race Riot

Andy Warhol (1964)

Race Riot crystallizes a split-second of state force: a police dog lunges while officers with batons surge and a ring of onlookers compresses the scene into a <strong>claustrophobic frieze</strong>. Warhol’s stark, high-contrast silkscreen translates a LIFE wire-photo into a <strong>mechanized emblem</strong> of American racial violence and its mass-media circulation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

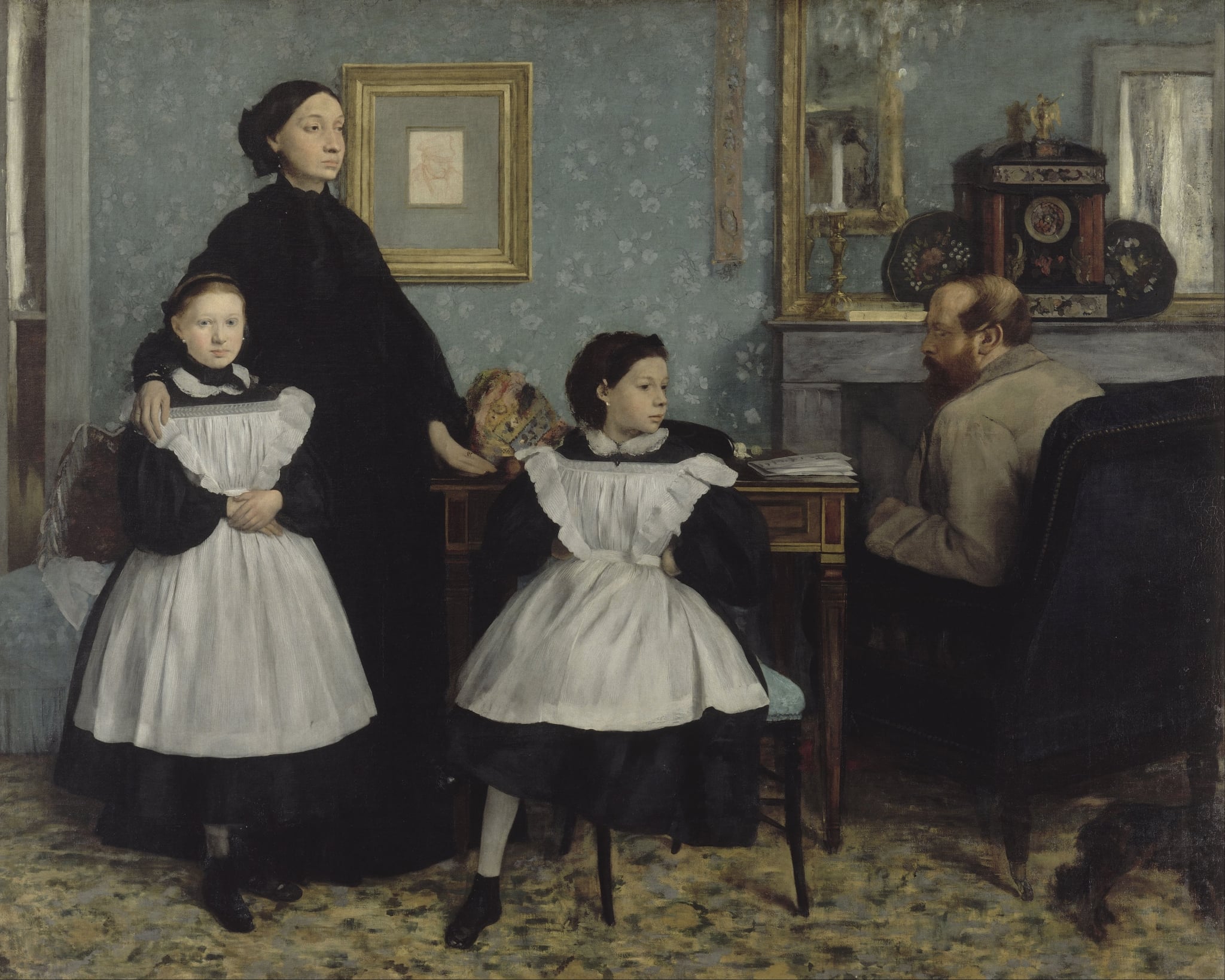

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Star

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1878)

Edgar Degas’s The Star shows a prima ballerina caught at the crest of a pose, her tutu a <strong>vaporous flare</strong> against a <strong>murky, tilted stage</strong>. Diagonal floorboards rush beneath her single pointe, while pale, ghostlike dancers linger in the wings, turning triumph into a scene of <strong>radiant isolation</strong> <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Édouard Manet (1867–1868)

Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian confronts state violence with a <strong>cool, reportorial</strong> style. The wall of gray-uniformed riflemen, the <strong>fragmented canvas</strong>, and the dispassionate loader at right turn the killing into <strong>impersonal machinery</strong> that implicates the viewer <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Ambassadors

Hans Holbein the Younger (1533)

Holbein’s The Ambassadors is a double-portrait staged before a green curtain, where shelves of scientific instruments, books, and musical devices enact <strong>Renaissance learning</strong> while an anamorphic <strong>skull</strong> and a veiled <strong>crucifix</strong> counter it with mortality and salvation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The work balances worldly status—fur, velvet, Oriental carpet—with a sober theology of limits amid the <strong>Reformation’s discord</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Doge's Palace

Claude Monet (1908)

Monet’s The Doge’s Palace translates Venice’s emblem of authority into an <strong>atmospheric drama</strong> of lilac, cream, and ultramarine. Architecture becomes a <strong>screen for light</strong>, as the ogival windows and double arcades blur into vibrating strokes mirrored by the lagoon’s <strong>second architecture</strong>—its reflection <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

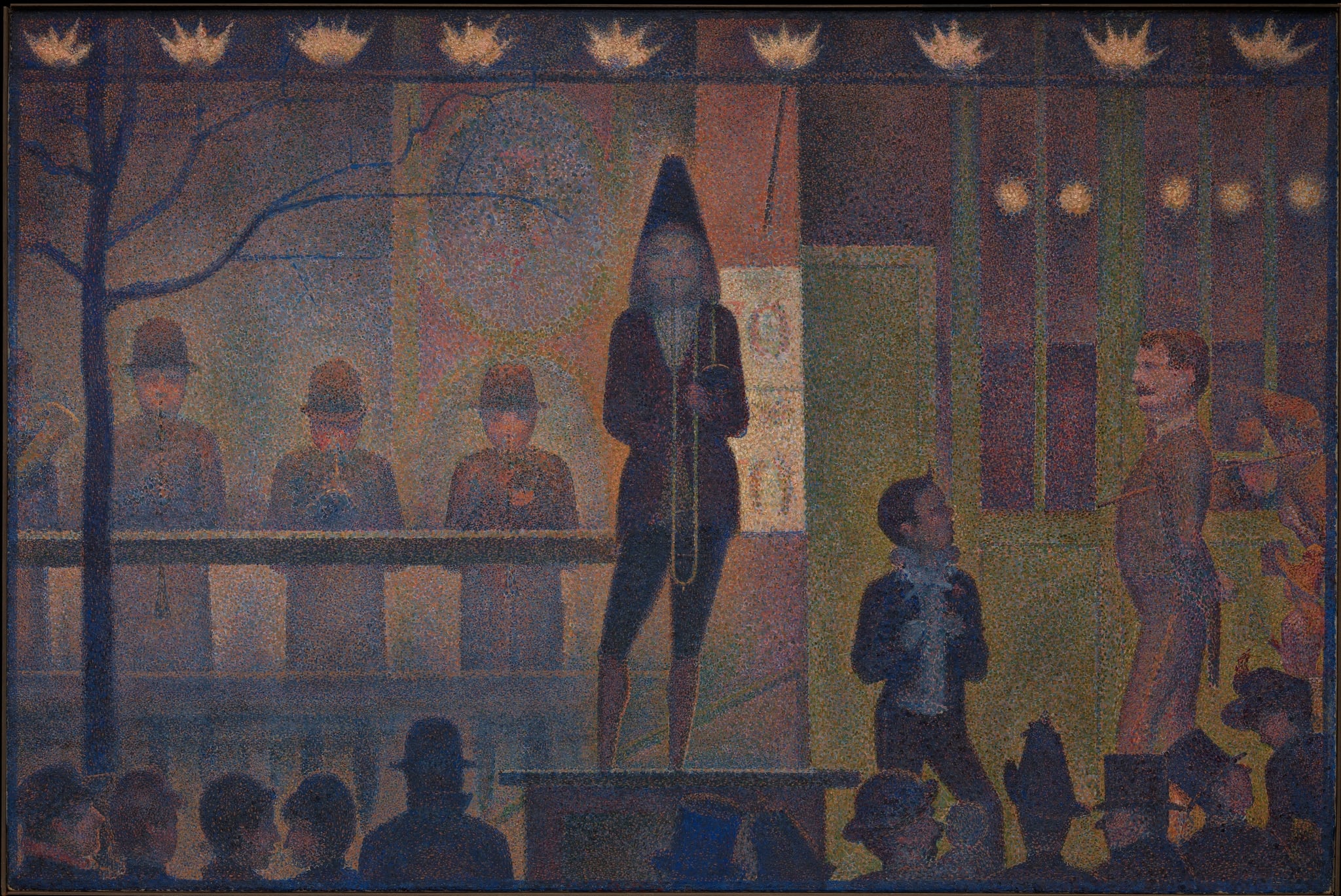

Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque)

Georges Seurat (1887–88)

Circus Sideshow (Parade de cirque) distills a bustling Paris fairground into a cool, ritualized <strong>threshold</strong> between street and spectacle. Under nine crownlike <strong>gaslights</strong>, a barker, musicians, and attendants align with geometric restraint while the crowd remains a band of silhouettes, held at the edge. Seurat’s <strong>Neo‑Impressionist</strong> dots make the night hum yet stay eerily still, turning publicity into a modern icon of order and mood <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge

Mary Cassatt (1879)

Mary Cassatt’s Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879) stages modern <strong>spectatorship</strong> inside a plush opera box, where a young woman in pink satin, pearls, and gloves occupies the red velvet seat while a mirror multiplies the chandeliers and balconies. Cassatt fuses <strong>intimacy</strong> and <strong>public display</strong>, using luminous brushwork to place her sitter within the social theater of Parisian leisure <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp

Rembrandt van Rijn (1632)

Rembrandt van Rijn turns a civic commission into a drama of <strong>knowledge made visible</strong>. A cone of light binds the ruff‑collared surgeons, the pale cadaver, and Dr. Tulp’s forceps as he raises the <strong>forearm tendons</strong> to explain the hand. Book and body face each other across the table, staging the tension—and alliance—between <strong>textual authority</strong> and <strong>empirical observation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Lady at the Tea Table

Mary Cassatt (1883–85 (signed 1885))

Mary Cassatt’s Lady at the Tea Table distills a domestic rite into a scene of <strong>quiet authority</strong>. The sitter’s black silhouette, lace cap, and poised hand marshal a regiment of <strong>cobalt‑and‑gold Canton porcelain</strong>, while tight cropping and planar light convert hospitality into <strong>modern self‑possession</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Still Life with Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers (1885) sets a jubilant bouquet in a pale, crackled vase against softly dissolving wallpaper and a wicker screen. With quick, clear strokes and a centered, oval mass, the painting unites <strong>Impressionist color</strong> with a <strong>classical, post-Italy structure</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The slight droop of blossoms turns the domestic scene into a gentle <strong>vanitas</strong>—a savoring of beauty before it fades <sup>[5]</sup>.

The Birth of Venus

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1484–1486)

In The Birth of Venus, <strong>Sandro Botticelli</strong> stages the sea-born goddess arriving on a <strong>scallop shell</strong>, blown ashore by intertwined <strong>winds</strong> and greeted by a flower-garlanded attendant who lifts a <strong>rose-patterned mantle</strong>. The painting’s crisp contours, elongated figures, and gilded highlights transform myth into an <strong>ideal of beauty</strong> that signals love, spring, and renewal <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Las Meninas

Diego Velazquez (1656)

In Las Meninas, a luminous Infanta anchors a shadowed studio where the painter pauses at a vast easel and a small wall mirror reflects the monarchs. The scene folds artist, sitters, and viewer into one reflexive tableau, turning court protocol into a meditation on <strong>seeing and being seen</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. A bright doorway at the rear deepens space and time, as if someone has just entered—or is leaving—the picture we occupy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The School of Athens

Raphael (1509–1511)

Raphael’s The School of Athens orchestrates a grand debate on knowledge inside a perfectly ordered, classical hall whose one-point perspective converges on the central pair, <strong>Plato</strong> and <strong>Aristotle</strong>. Their opposed gestures—one toward the heavens, one level to the earth—establish the fresco’s governing dialectic between <strong>ideal forms</strong> and <strong>empirical reason</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Around them, mathematicians, scientists, and poets cluster under statues of <strong>Apollo</strong> and <strong>Athena/Minerva</strong>, turning the room into a temple of <strong>Renaissance humanism</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper (1942)

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks turns a corner diner into a sealed stage where <strong>fluorescent light</strong> and <strong>curved glass</strong> hold four figures in suspended time. The empty streets and the “PHILLIES” cigar sign sharpen the sense of <strong>urban solitude</strong> while hinting at wartime vigilance. The result is a cool, lucid image of modern life: illuminated, open to view, and emotionally out of reach.

The Elephants

Salvador Dali (1948)

In The Elephants, Salvador Dali distills a stark paradox of <strong>weight and weightlessness</strong>: gaunt elephants tiptoe on <strong>stilt-thin legs</strong> while bearing stone <strong>obelisks</strong>. The blazing red-orange sky and tiny human figures compress ambition into a vision of <strong>precarious power</strong> and time stretched thin <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Gleaners

Jean-Francois Millet (1857)

Three peasant women bend in a solemn rhythm, gleaning leftover stalks under a dry, late-afternoon light. In the far distance, tiny carts, haystacks, and an overseer on horseback signal abundance and authority, while the foreground figures loom with <strong>monumental gravity</strong>, asserting the dignity of labor amid inequality <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Raft of the Medusa

Theodore Gericault (1818–1819)

The Raft of the Medusa stages a modern catastrophe as epic tragedy, pivoting from corpses to a surge of <strong>collective hope</strong>. The diagonal mast, torn sail, and a Black figure waving a cloth toward a tiny ship compress the moment when despair turns to <strong>precarious rescue</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.