Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1801–1805 (series of five versions)

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- c. 261 x 221 cm (Malmaison version)

- Location

- Musée national des châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois‑Préau, Rueil‑Malmaison

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about Napoleon Crossing the Alps

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Historical Context: A Networked Image of Rule

Source: Foundation Napoléon; Malmaison; SPSG Charlottenburg; RMN-Grand Palais; Belvedere

Formal Analysis: Neoclassicism Without Allegory

Source: Smarthistory; Encyclopaedia Britannica; scholarly synthesis via Wikipedia entry

Symbolic Reading: Rock as Imperial Chronicle

Source: Smarthistory; Foundation Napoléon

Psychology of Command: Gesture, Gaze, and Color

Source: Smarthistory; Encyclopaedia Britannica

Art & Representation: Fabrication and Truth-Effects

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica; scholarly synthesis via Wikipedia entry

Related Themes

About Jacques-Louis David

More by Jacques-Louis David

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David (1784 (exhibited 1785))

In The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David crystallizes <strong>civic duty over private feeling</strong>: three Roman brothers extend their arms to swear allegiance as their father raises <strong>three swords</strong> at the perspectival center. The painting’s severe geometry, austere architecture, and polarized groups of <strong>rectilinear men</strong> and <strong>curving mourners</strong> stage a manifesto of <strong>Neoclassical virtue</strong> and republican resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

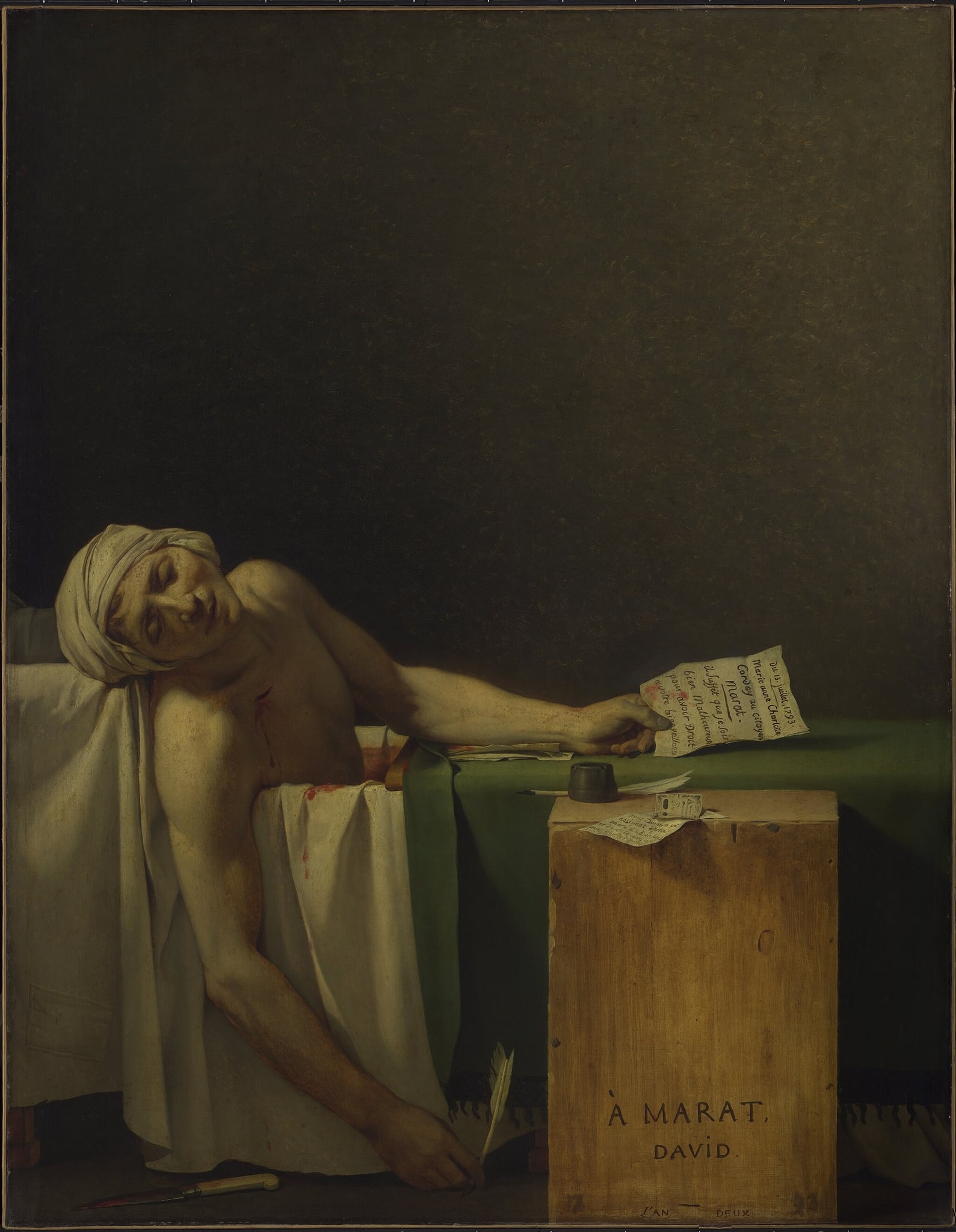

The Death of Marat

Jacques-Louis David (1793)

<strong>The Death of Marat</strong> turns a private murder into a <strong>secular martyrdom</strong>: Marat’s idealized body slumps in a bath, a pleading letter in his hand, a quill slipping from the other beside a bloodied knife and inkwell. Against a vast dark void, David’s calm light and austere geometry elevate humble objects—the green baize plank and the crate inscribed “À MARAT, DAVID, L’AN DEUX”—into civic emblems <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.