Seasons & cycles

Featured Artworks

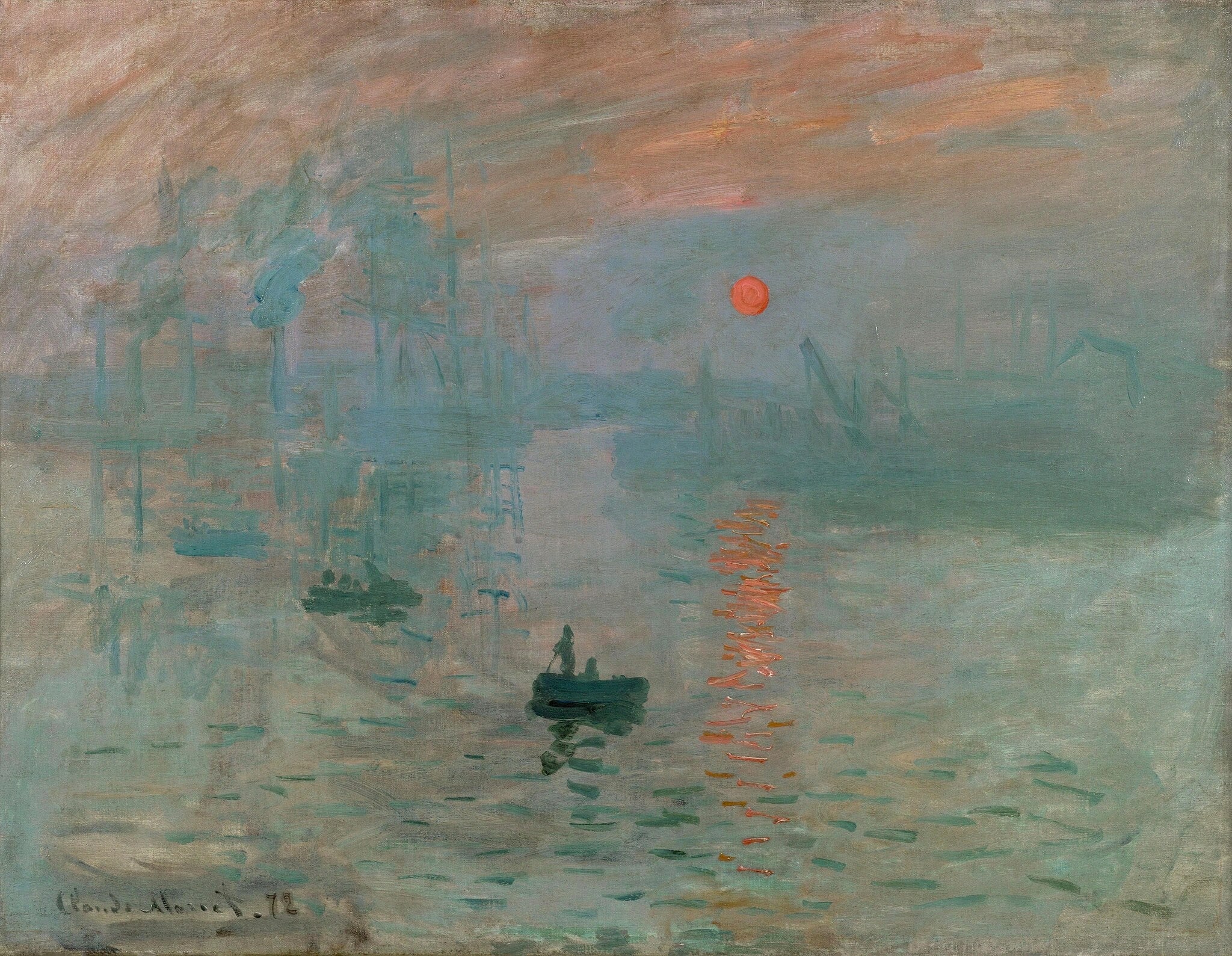

Impression, Sunrise

Claude Monet (1872)

In Impression, Sunrise, Claude Monet turns Le Havre’s fog-bound harbor into an experiment in <strong>immediacy</strong> and <strong>modernity</strong>. Cool blue-greens dissolve cranes, masts, and smoke, while a small skiff cuts the water beneath a blazing, <strong>equiluminant</strong> orange sun whose vertical reflection stitches the scene together <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The effect is a poised dawn where industry meets nature, a quiet <strong>awakening</strong> rendered through light rather than line.

The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive)

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s The Train in the Snow (The Locomotive) (1875) turns a suburban winter platform into a study of <strong>modernity absorbed by atmosphere</strong>. The engine’s twin yellow headlights and a smear of red push through a world of greys and violets as steam fuses with the low sky, while the right-hand fence and bare trees drill depth and cadence into the scene <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Monet fixes not an object but a <strong>moment of perception</strong>, where industry seems to dematerialize into weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Giverny

Claude Monet (1900)

In The Artist's Garden at Giverny, Claude Monet turns his cultivated Clos Normand into a field of living color, where bands of violet <strong>irises</strong> surge toward a narrow, rose‑colored path. Broken, flickering strokes let greens, purples, and pinks mix optically so that light seems to tremble across the scene, while lilac‑toned tree trunks rhythmically guide the gaze inward <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Water Lily Pond

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond transforms a designed garden into a theater of <strong>perception and reflection</strong>. The pale, arched <strong>Japanese bridge</strong> hovers over a surface where lilies, reeds, and mirrored willow fronds dissolve boundaries between water and sky, proposing <strong>seeing itself</strong> as the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Morning on the Seine (series)

Claude Monet (1897)

Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine (series) turns dawn into an inquiry about <strong>perception</strong> and <strong>time</strong>. In this canvas, the left bank’s shadowed foliage dissolves into lavender mist while a pale radiance opens at right, fusing sky and water into a single, reflective field <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

After the Luncheon

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1879)

After the Luncheon crystallizes a <strong>suspended instant</strong> of Parisian leisure: coffee finished, glasses dappled with light, and a cigarette just being lit. Renoir’s <strong>shimmering brushwork</strong> and the trellised spring foliage turn the scene into a tapestry of conviviality where time briefly pauses.

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Sunflowers

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is a <strong>yellow-on-yellow</strong> still life that stages a full <strong>cycle of life</strong> in fifteen blooms, from fresh buds to brittle seed heads. The thick impasto, green shocks of stem and bract, and the vase signed <strong>“Vincent”</strong> turn a humble bouquet into an emblem of endurance and fellowship <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Jeanne (Spring)

Édouard Manet (1881)

Édouard Manet’s Jeanne (Spring) fuses a time-honored allegory with <strong>modern Parisian fashion</strong>: a crisp profile beneath a cream parasol, set against <strong>luminous, leafy greens</strong>. Manet turns couture—hat, glove, parasol—into the language of <strong>renewal and youth</strong>, making spring feel both perennial and up-to-the-minute <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Wheatfield with Crows

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

A panoramic wheatfield splits around a rutted track under a storm-charged sky while black crows rush toward us. Van Gogh drives complementary blues and yellows into collision, fusing <strong>nature’s vitality</strong> with <strong>inner turbulence</strong>.

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

Claude Monet (1908–1912)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk fuses the Benedictine church’s dark silhouette with a sky flaming from apricot to cobalt, turning architecture into atmosphere. The campanile’s vertical and its wavering reflection anchor a sea of trembling color, staging a meditation on <strong>permanence</strong> and <strong>flux</strong>.

The Artist's Garden at Vétheuil

Claude Monet (1881)

Claude Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil stages a sunlit ascent through a corridor of towering sunflowers toward a modest house, where everyday life meets cultivated nature. Quick, broken strokes make leaves and shadows tremble, asserting <strong>light</strong> and <strong>painterly surface</strong> over linear contour. Blue‑and‑white <strong>jardinieres</strong> anchor the foreground, while a child and dog briefly pause on the path, turning the garden into a <strong>domestic sanctuary</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Félix Fénéon

Paul Signac (1890)

Portrait of Félix Fénéon turns a critic into a <strong>conductor of color</strong>: a dandy in a yellow coat proffers a delicate cyclamen as concentric disks, whiplash arabesques, stars, and palette-like circles whirl around him. Rendered in precise <strong>Pointillist</strong> dots, the scene stages the fusion of <strong>art, science, and modern style</strong>.<sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>

Flood at Port-Marly

Alfred Sisley (1876)

In Flood at Port-Marly, Alfred Sisley turns a flooded street into a reflective stage where <strong>human order</strong> and <strong>natural flux</strong> converge. The aligned, leafless trees function like measuring rods against the water, while flat-bottomed boats replace carriages at the curb. With cool, silvery strokes and a cloud-laden sky, Sisley asserts that the scene’s true drama is <strong>atmosphere</strong> and <strong>adaptation</strong>, not catastrophe <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Japanese Bridge

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Japanese Bridge centers a pale <strong>blue‑green arch</strong> above a horizonless pond, where water‑lily pads and blossoms punctuate a field of shifting reflections. The bridge reads as both structure and <strong>contemplative threshold</strong>, suspending the eye between surface shimmer and mirrored depths <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

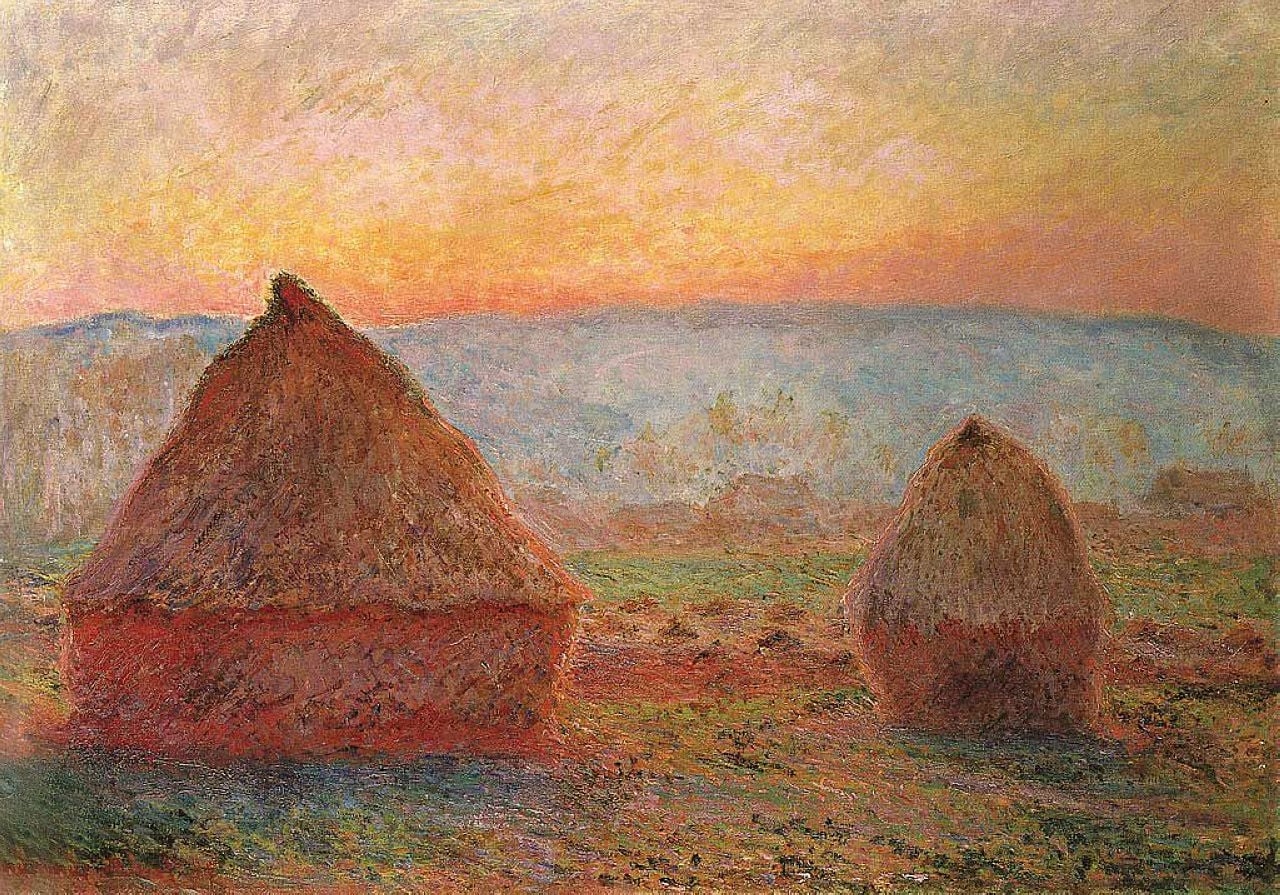

Haystack, Sunset

Claude Monet (1891)

Two conical stacks blaze against a cooling horizon, turning stored grain into a drama of <strong>light, time, and rural wealth</strong>. Monet’s broken strokes fuse warm oranges and cool violets so the stacks seem to glow from within, embodying the <strong>transience</strong> of a single sunset and the <strong>endurance</strong> of agrarian cycles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Poplars on the Epte

Claude Monet (1891)

Claude Monet’s Poplars on the Epte turns a modest river bend into a meditation on <strong>time, light, and perception</strong>. Upright trunks register as steady <strong>vertical chords</strong>, while their broken, shimmering reflections loosen form into <strong>pure sensation</strong>. The image stages a tension between <strong>order and flux</strong> that anchors the series within Impressionism’s core aims <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Boulevard des Capucines

Claude Monet (1873–1874)

From a high perch above Paris, Claude Monet turns the Haussmann boulevard into a living current of <strong>light, weather, and motion</strong>. Leafless trees web the view, crowds dissolve into <strong>flickering strokes</strong>, and a sudden <strong>pink cluster of balloons</strong> pierces the cool winter scale <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Still Life with Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life with Flowers (1885) sets a jubilant bouquet in a pale, crackled vase against softly dissolving wallpaper and a wicker screen. With quick, clear strokes and a centered, oval mass, the painting unites <strong>Impressionist color</strong> with a <strong>classical, post-Italy structure</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The slight droop of blossoms turns the domestic scene into a gentle <strong>vanitas</strong>—a savoring of beauty before it fades <sup>[5]</sup>.

The Birth of Venus

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1484–1486)

In The Birth of Venus, <strong>Sandro Botticelli</strong> stages the sea-born goddess arriving on a <strong>scallop shell</strong>, blown ashore by intertwined <strong>winds</strong> and greeted by a flower-garlanded attendant who lifts a <strong>rose-patterned mantle</strong>. The painting’s crisp contours, elongated figures, and gilded highlights transform myth into an <strong>ideal of beauty</strong> that signals love, spring, and renewal <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa

Hokusai (ca. 1830–32)

The Great Wave off Kanagawa distills a universal drama: fragile laboring boats face a <strong>towering breaker</strong> while <strong>Mount Fuji</strong> sits small yet immovable. Hokusai wields <strong>Prussian blue</strong> to sculpt depth and cold inevitability, fusing ukiyo‑e elegance with Western perspective to stage nature’s power against human resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Hay Wain

John Constable (1821)

Set beside Willy Lott’s cottage on the River Stour, The Hay Wain stages a moment of <strong>unhurried rural labor</strong>: an empty timber cart, drawn by three horses with red-collared tack, pauses mid‑ford as weather shifts above. Constable fuses <strong>empirical observation</strong>—rippling reflections, chimney smoke, flickers of white on leaves—with a composed vista of fields opening to sun. The result is a serene yet alert meditation on <strong>work, weather, and continuity</strong> in the English countryside <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Tree of Life

Gustav Klimt (1910–1911 (design; mosaic installed 1911))

Gustav Klimt’s The Tree of Life crystallizes a <strong>cosmological axis</strong> in a gilded ornamental language: a rooted trunk erupts into <strong>endless spirals</strong>, embedded with <strong>eye-like rosettes</strong> and shadowed by a black, red‑eyed bird. Designed as part of the Stoclet dining‑room frieze, it fuses <strong>symbolism and luxury materials</strong> to link earthly abundance with timeless transcendence <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.