Childhood & innocence

Featured Artworks

Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore

Mary Cassatt (c. 1886)

Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Big Straw Hat and a Pinafore distills childhood into a quiet drama of <strong>interiority</strong> and <strong>constraint</strong>. The oversized straw hat and plain pinafore bracket a flushed face, downcast eyes, and <strong>clasped hands</strong>, turning a simple pose into a study of modern self‑consciousness <sup>[1]</sup>. Cassatt’s cool grays and swift, luminous strokes make mood—not costume—the subject.

Breakfast in Bed

Mary Cassatt (1897)

Breakfast in Bed distills a <strong>tender modern intimacy</strong> into a tightly cropped sanctuary of rumpled white linens, protective embrace, and interrupted routine. Mary Cassatt uses <strong>cool light</strong> against <strong>warm flesh</strong> to anchor attention on the mother’s encircling arm and the child’s outward gaze, fusing care, curiosity, and the rhythms of <strong>everyday modern life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Children Playing on the Beach

Mary Cassatt (1884)

In Children Playing on the Beach, Mary Cassatt brings the viewer down to a child’s eye level, granting everyday play the weight of <strong>serious, self-contained work</strong>. The cool horizon and tiny boats open onto <strong>modern space and possibility</strong>, while the cropped, tilted foreground seals us inside the children’s focused world <sup>[1]</sup>.

A Woman and a Girl Driving

Mary Cassatt (1881)

Cassatt stages a modern scene of <strong>female control</strong> in motion: a woman grips the reins and whip while a girl beside her mirrors the pose, and a groom seated behind looks away. The cropped horse and diagonal harness thrust the carriage forward, placing viewers inside a public outing in the Bois de Boulogne—an arena where visibility signaled status and autonomy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Summertime

Mary Cassatt (1894)

Mary Cassatt’s Summertime (1894) stages a quiet drama of <strong>attentive looking</strong>: a woman and a girl lean from a cropped boat toward two ducks as the lake flickers with broken color. Cassatt fuses <strong>Impressionism</strong> and <strong>Japonisme</strong>—no horizon, tipped perspective, and abrupt cropping—to press our gaze downward into light-spattered water. The result is an image of <strong>modern leisure</strong> that is also a study of perception itself <sup>[1]</sup>.

Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt

Mary Cassatt (1884)

A quiet, domestic tableau becomes a study in <strong>authority tempered by affection</strong>. In Portrait of Alexander J. Cassatt and His Son Robert Kelso Cassatt, Mary Cassatt fuses father and child into a single dark silhouette against a luminous, brushed interior, their shared gaze fixed beyond the frame. The <strong>newspaper</strong>, <strong>linked hands</strong>, and <strong>cropped closeness</strong> transform a routine moment into a symbol of generational continuity and modern attentiveness.

Madame Monet and Her Son

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s 1874 canvas Madame Monet and Her Son crystallizes <strong>modern domestic leisure</strong> and <strong>plein‑air immediacy</strong> in Argenteuil. A luminous white dress pools into light while a child in a pale‑blue sailor suit reclines diagonally; a strutting rooster punctuates the greens with warm color. The brushwork fuses figure and garden so the moment reads as <strong>lived, not staged</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Child's Bath

Mary Cassatt (1893)

Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (1893) recasts an ordinary ritual as <strong>modern devotion</strong>. From a steep, print-like vantage, interlocking stripes, circles, and diagonals focus attention on <strong>touch, care, and renewal</strong>, turning domestic labor into a subject of high art <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The work synthesizes Impressionist sensitivity with <strong>Japonisme</strong> design to monumentalize the private sphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Vétheuil

Claude Monet (1881)

Claude Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil stages a sunlit ascent through a corridor of towering sunflowers toward a modest house, where everyday life meets cultivated nature. Quick, broken strokes make leaves and shadows tremble, asserting <strong>light</strong> and <strong>painterly surface</strong> over linear contour. Blue‑and‑white <strong>jardinieres</strong> anchor the foreground, while a child and dog briefly pause on the path, turning the garden into a <strong>domestic sanctuary</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

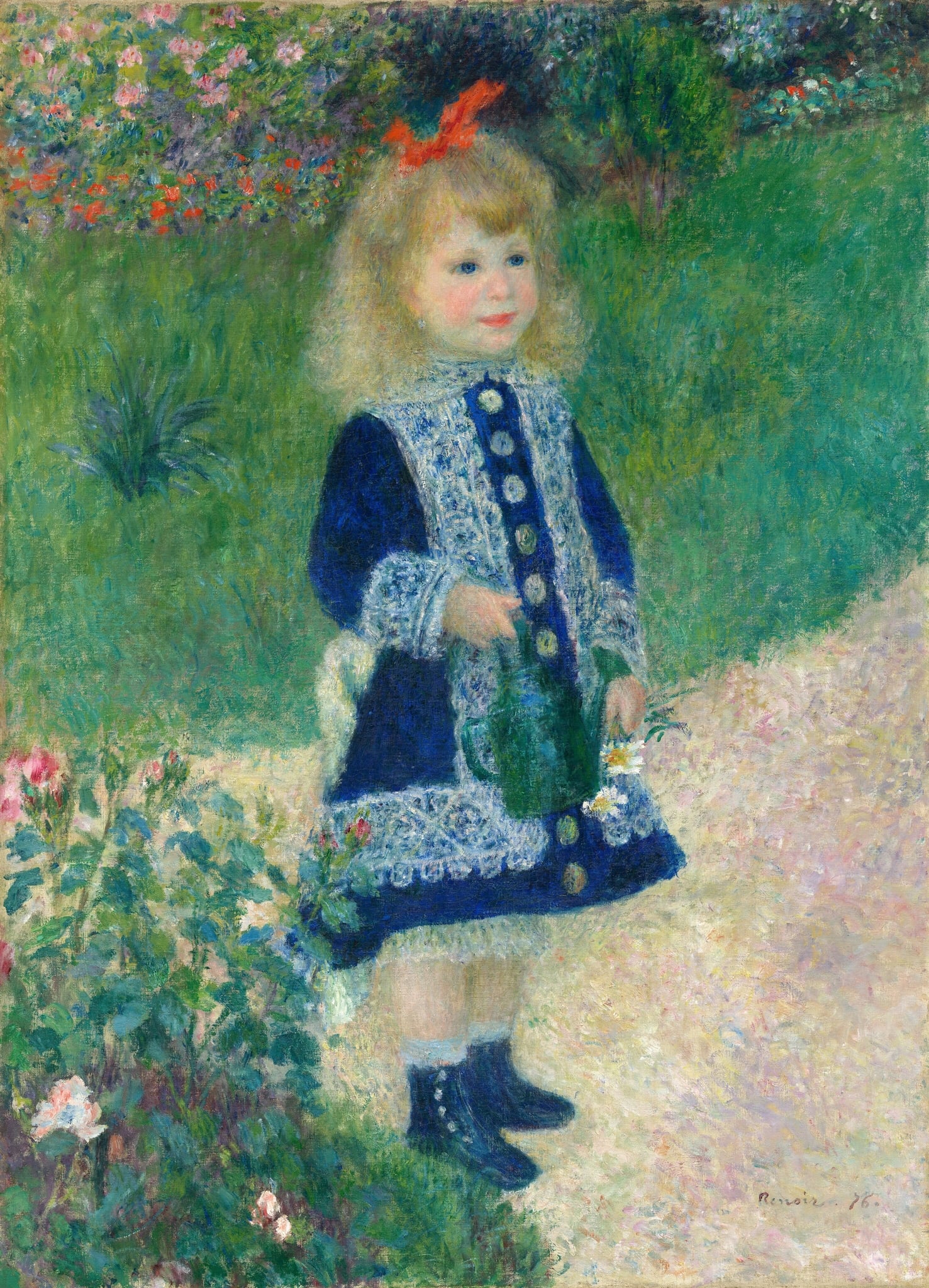

Girl with a Watering Can

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

Renoir’s 1876 Girl with a Watering Can fuses a crisply perceived child with a dissolving garden atmosphere, using <strong>prismatic color</strong> and <strong>controlled facial modeling</strong> to stage innocence within modern leisure <sup>[1]</sup>. The cobalt dress, red bow, and green can punctuate a haze of pinks and greens, making nurture and growth the scene’s quiet thesis.

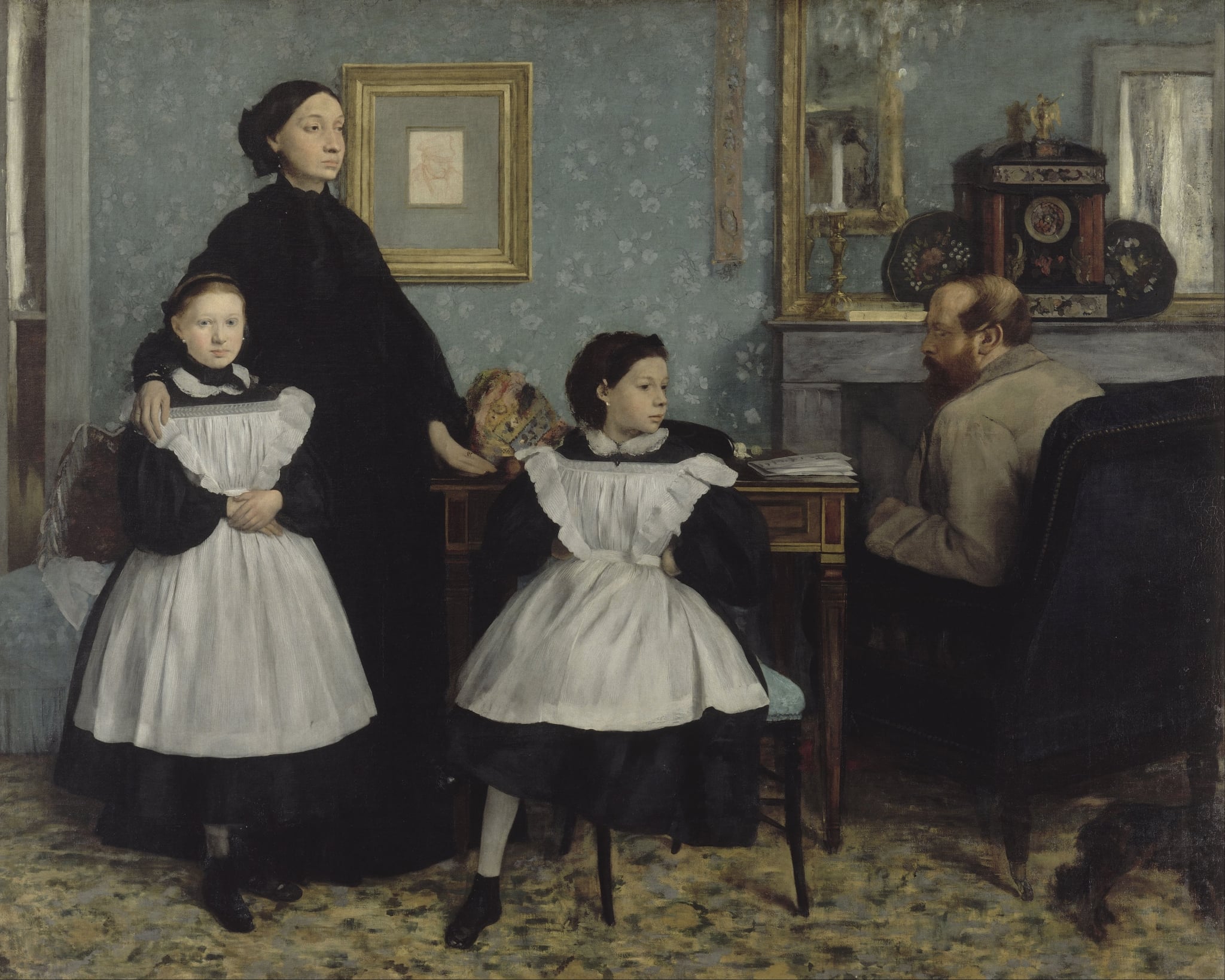

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Umbrellas

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1881–86)

A sudden shower turns a Paris street into a lattice of <strong>slate‑blue umbrellas</strong>, knitting strangers into a single moving frieze. A bareheaded young woman with a <strong>bandbox</strong> strides forward while a bourgeois mother and children cluster at right, their <strong>hoop</strong> echoing the umbrellas’ arcs <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

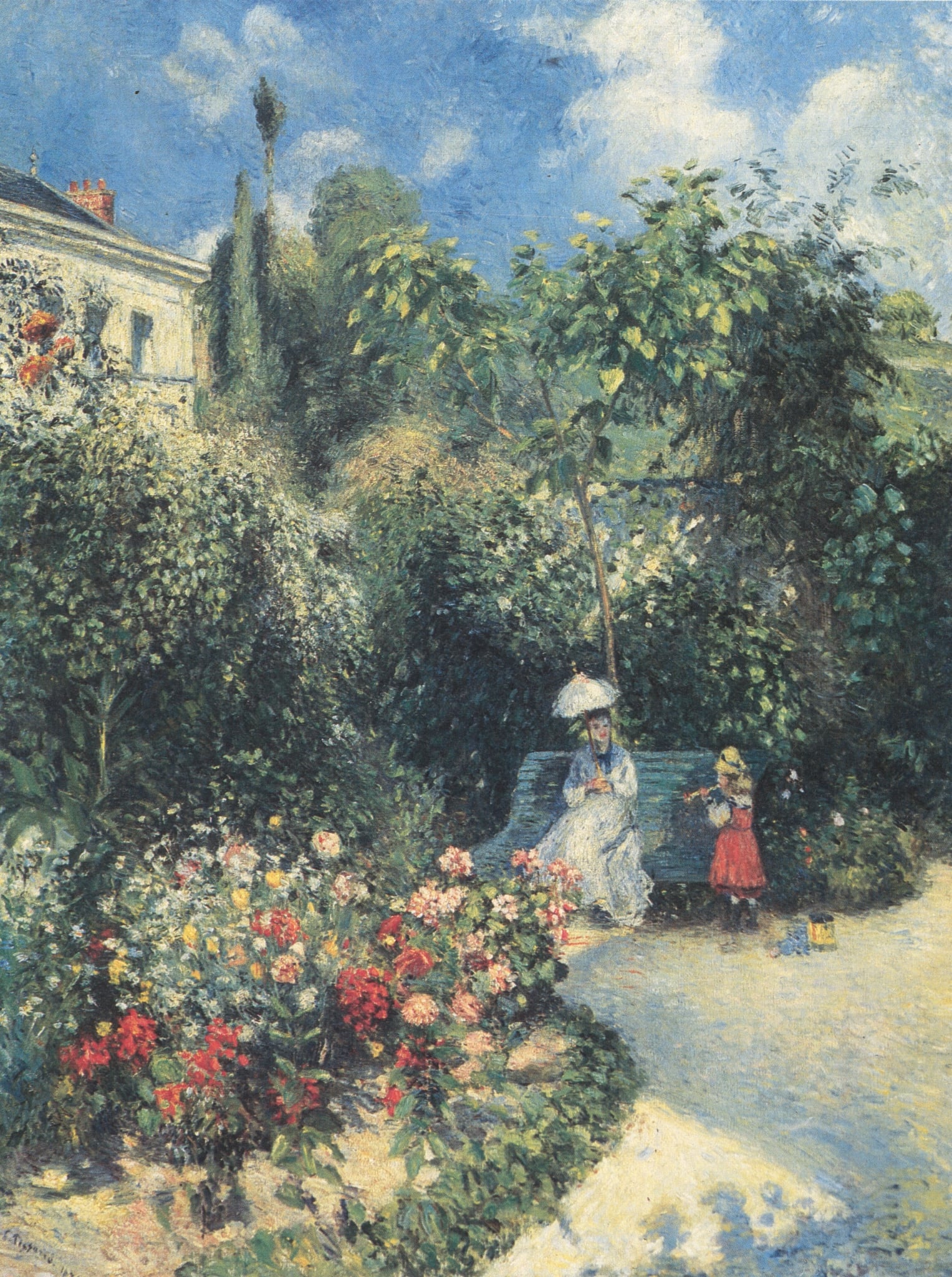

The Garden of Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (1874)

In The Garden of Pontoise, Camille Pissarro turns a modest suburban plot into a stage for <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>fugitive light</strong>. A woman shaded by a parasol and a child in a bright red skirt punctuate the deep greens, while a curving sand path and beds of red–pink blossoms draw the eye toward a pale house and cloud‑flecked sky. The painting asserts that everyday, cultivated nature can be a <strong>modern Eden</strong> where time, season, and social ritual quietly unfold <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Little Girl in a Blue Armchair

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s Little Girl in a Blue Armchair renders a child slumped diagonally across an oversized seat, surrounded by a flotilla of blue chairs and cool window light. With brisk, broken strokes and a skewed recession, Cassatt asserts a modern, unsentimental view of childhood—bored, autonomous, and <strong>out of step with adult decorum</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. Subtle collaboration with <strong>Degas</strong> in the background design sharpens the picture’s daring spatial thrust <sup>[2]</sup>.

Children on the Seashore, Guernsey

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (about 1883)

Renoir’s Children on the Seashore, Guernsey crystallizes a wind‑bright moment of modern leisure with <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a gently choreographed group of children. The central girl in a white dress and black feathered hat steadies a toddler while a pink‑clad companion leans in and a sailor‑suited boy rests on the pebbles—an intimate triangle set against a <strong>shimmering, populated sea</strong>. The canvas makes light and movement the protagonists, dissolving edges into <strong>pearly surf and sun‑washed cliffs</strong>.

Las Meninas

Diego Velazquez (1656)

In Las Meninas, a luminous Infanta anchors a shadowed studio where the painter pauses at a vast easel and a small wall mirror reflects the monarchs. The scene folds artist, sitters, and viewer into one reflexive tableau, turning court protocol into a meditation on <strong>seeing and being seen</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. A bright doorway at the rear deepens space and time, as if someone has just entered—or is leaving—the picture we occupy <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child

Mary Cassatt (1880)

Mary Cassatt’s Mother About to Wash Her Sleepy Child (1880) turns an ordinary bedtime ritual into a scene of <strong>caregiving, labor, and modern intimacy</strong>. Cropped close, with the child’s legs diagonally splayed and a tilted washbowl at the mother’s knee, the picture translates domestic routine into a <strong>modern Madonna</strong> for the bourgeois interior. Its flickering blues and milky whites, plus patterned upholstery and wallpaper, signal Cassatt’s <strong>Impressionist</strong> and japonisme-inflected design sense <sup>[2]</sup>.

Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror)

Mary Cassatt (ca. 1899)

Mary Cassatt’s Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror) turns a routine act of care into a <strong>modern icon</strong>. An oval mirror <strong>haloes</strong> the child while interlaced hands and close bodies make <strong>touch</strong> the vehicle of meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.