Revolution & upheaval

Featured Artworks

The Oath of the Horatii

Jacques-Louis David (1784 (exhibited 1785))

In The Oath of the Horatii, Jacques-Louis David crystallizes <strong>civic duty over private feeling</strong>: three Roman brothers extend their arms to swear allegiance as their father raises <strong>three swords</strong> at the perspectival center. The painting’s severe geometry, austere architecture, and polarized groups of <strong>rectilinear men</strong> and <strong>curving mourners</strong> stage a manifesto of <strong>Neoclassical virtue</strong> and republican resolve <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

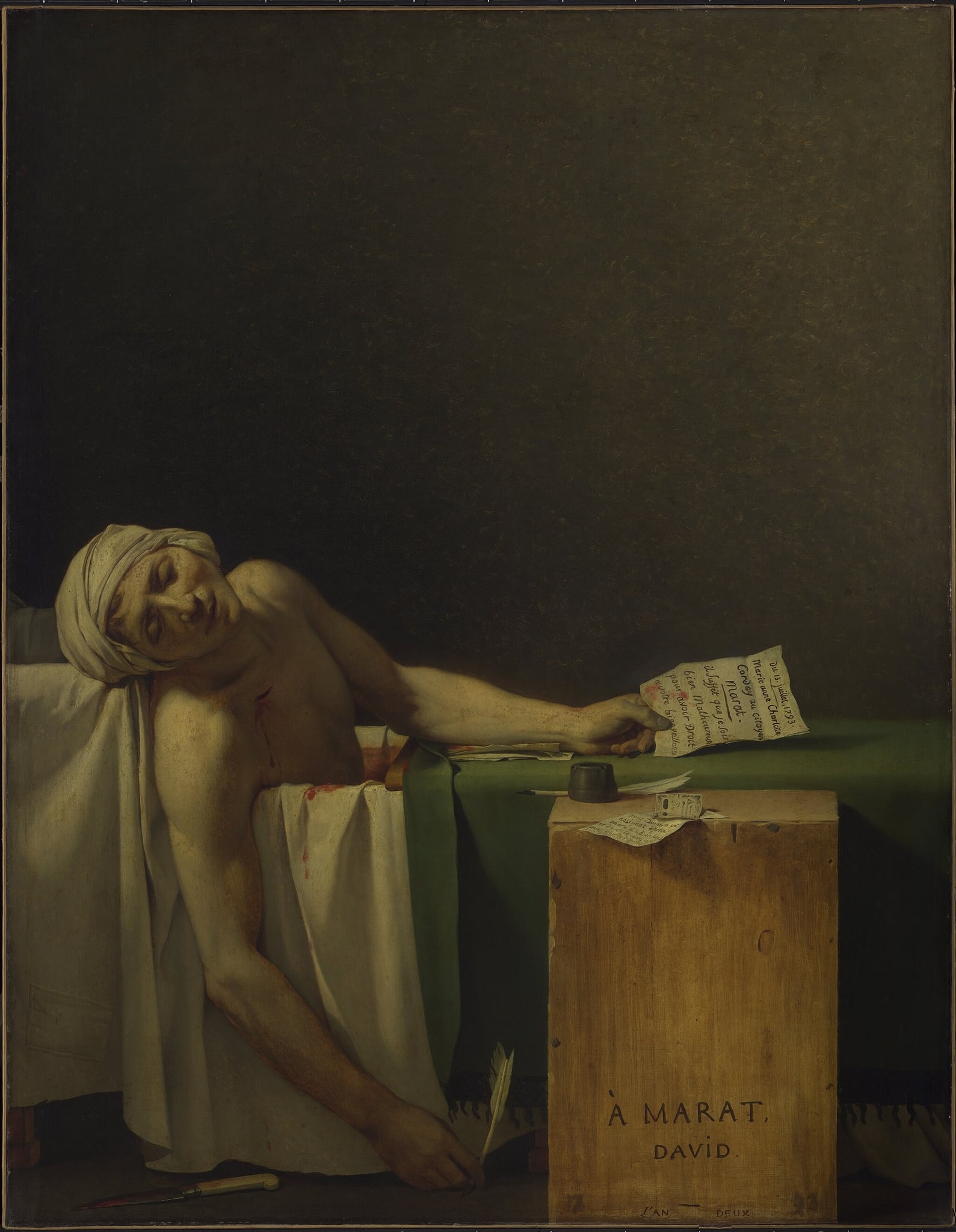

The Death of Marat

Jacques-Louis David (1793)

<strong>The Death of Marat</strong> turns a private murder into a <strong>secular martyrdom</strong>: Marat’s idealized body slumps in a bath, a pleading letter in his hand, a quill slipping from the other beside a bloodied knife and inkwell. Against a vast dark void, David’s calm light and austere geometry elevate humble objects—the green baize plank and the crate inscribed “À MARAT, DAVID, L’AN DEUX”—into civic emblems <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Liberty Leading the People

Eugene Delacroix (1830)

<strong>Liberty Leading the People</strong> turns a real street uprising into a modern myth: a bare‑breasted Liberty in a <strong>Phrygian cap</strong> thrusts the <strong>tricolor</strong> forward as Parisians of different classes surge over corpses and rubble. Delacroix binds allegory to eyewitness detail—Notre‑Dame flickers through smoke, a bourgeois in a top hat shoulders a musket, and a pistol‑waving boy keeps pace—so that freedom appears as both idea and action <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. After its 2024 cleaning, sharper blues, whites, and reds re‑ignite the painting’s charged color drama <sup>[4]</sup>.