Nature

In modern painting, Nature symbolism shifts from a stable backdrop of pastoral harmony and cyclical time to an arena where light, atmosphere, and perception themselves become the principal bearers of meaning.

Featured Artworks

Bathers by Paul Cézanne: Geometry of the Modern Nude

Paul Cézanne

In Bathers, Paul Cézanne arranges a circle of generalized nudes beneath arching trees that meet like a <strong>natural vault</strong>, staging bathing as a timeless rite rather than a specific story. His <strong>constructive brushwork</strong> fuses bodies, water, and sky into one geometric order, balancing cool blues with warm ochres. The scene proposes a measured <strong>harmony between figure and landscape</strong>, a culmination of Cézanne’s search for enduring structure <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Gare Saint-Lazare

Claude Monet (1877)

Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare turns an iron-and-glass train shed into a theater of <strong>steam, light, and motion</strong>. Twin locomotives, gas lamps, and a surge of figures dissolve into bluish vapor under the diagonal canopy, recasting industrial smoke as <strong>luminous atmosphere</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

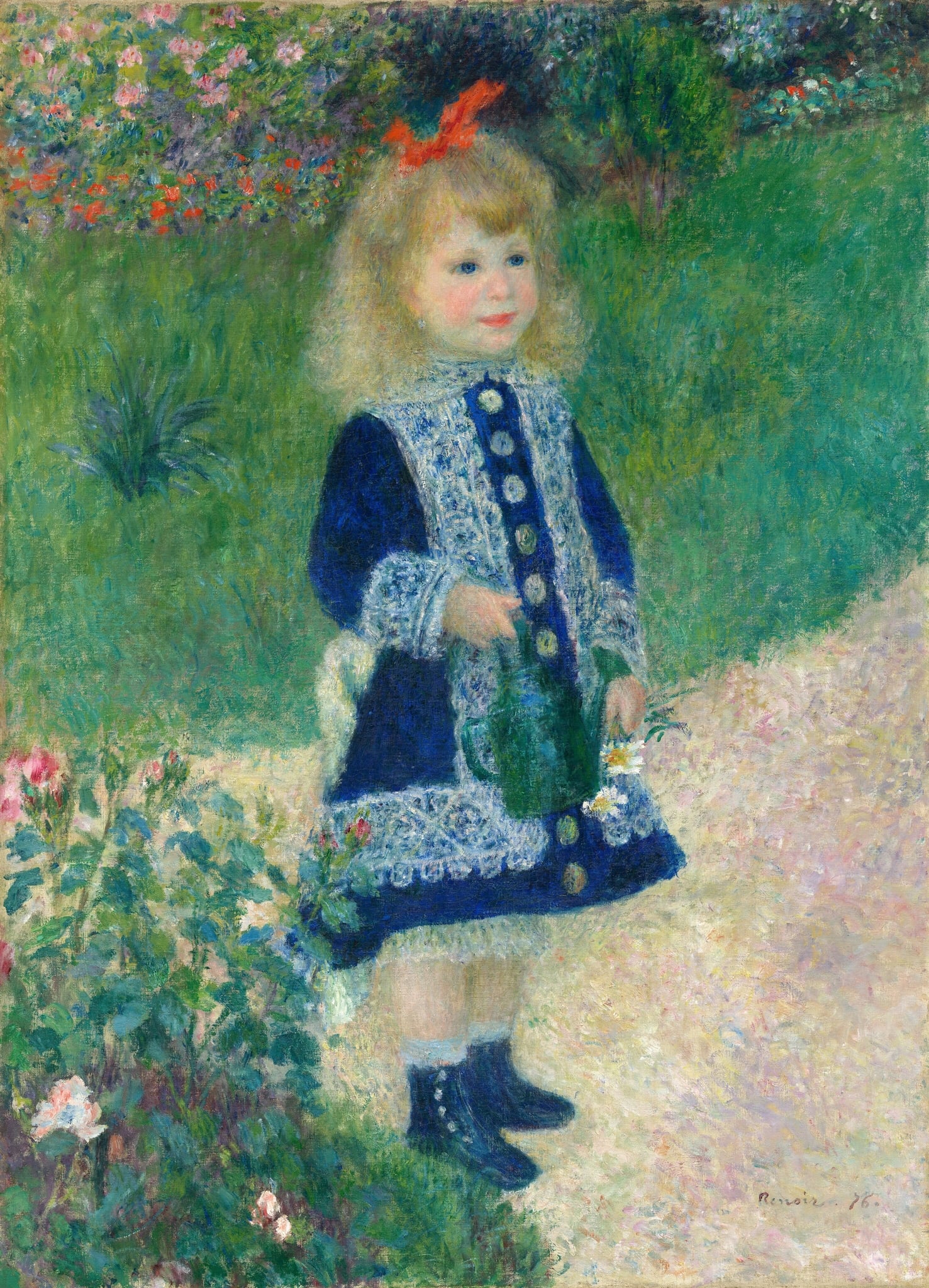

Girl with a Watering Can

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

Renoir’s 1876 Girl with a Watering Can fuses a crisply perceived child with a dissolving garden atmosphere, using <strong>prismatic color</strong> and <strong>controlled facial modeling</strong> to stage innocence within modern leisure <sup>[1]</sup>. The cobalt dress, red bow, and green can punctuate a haze of pinks and greens, making nurture and growth the scene’s quiet thesis.

Haystacks Series by Claude Monet | Light, Time & Atmosphere

Claude Monet

Claude Monet’s <strong>Haystacks Series</strong> transforms a routine rural subject into an inquiry into <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunset view, the stacks swell at the left while the sun burns through the gap, making the field shimmer with <strong>apricot, lilac, and blue</strong> vibrations.

Houses of Parliament

Claude Monet (1903)

Claude Monet’s Houses of Parliament renders Westminster as a <strong>dissolving silhouette</strong> in a wash of peach, mauve, and pale gold, where stone and river are leveled by <strong>luminous fog</strong>. Short, vibrating strokes turn architecture into <strong>atmosphere</strong>, while a tiny boat anchors human scale amid the monumental scene.

Irises

Vincent van Gogh (1889)

Painted in May 1889 at the Saint-Rémy asylum garden, Vincent van Gogh’s <strong>Irises</strong> turns close observation into an act of repair. Dark contours, a cropped, print-like vantage, and vibrating complements—violet/blue blossoms against <strong>yellow-green</strong> ground—stage a living frieze whose lone <strong>white iris</strong> punctuates the field with arresting clarity <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

La Grenouillère

Claude Monet (1869)

Monet’s La Grenouillère crystallizes the new culture of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine: crowded bathers, promenading couples, and rental boats orbit a floating resort. With <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> and a high-key palette, Monet turns water, light, and movement into the true subjects, suspending the scene at the brink of dissolving.

On the Beach

Édouard Manet (1873)

On the Beach captures a paused interval of modern leisure: two fashionably dressed figures sit on pale sand before a <strong>banded, high-horizon sea</strong>. Manet’s <strong>economical brushwork</strong>, restricted greys and blacks, and radical cropping stage a scene of absorption and wind‑tossed motion that feels both intimate and detached <sup>[1]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Rouen Cathedral Series

Claude Monet (1894)

Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral Series (1892–94) turns a Gothic monument into a laboratory of <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunstruck façade, portals, gables, and a warm, orange-tinged rose window flicker in pearly violets and buttery yellows against a crystalline blue sky, while tiny figures at the base anchor the scale. The painting insists that <strong>light—not stone—is the true subject</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Giverny

Claude Monet (1900)

In The Artist's Garden at Giverny, Claude Monet turns his cultivated Clos Normand into a field of living color, where bands of violet <strong>irises</strong> surge toward a narrow, rose‑colored path. Broken, flickering strokes let greens, purples, and pinks mix optically so that light seems to tremble across the scene, while lilac‑toned tree trunks rhythmically guide the gaze inward <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Cliff Walk at Pourville

Claude Monet (1882)

Claude Monet’s The Cliff Walk at Pourville renders wind, light, and sea as interlocking forces through <strong>shimmering, broken brushwork</strong>. Two small walkers—one beneath a pink parasol—stand near the <strong>precipitous cliff edge</strong>, their presence measuring the vastness of turquoise water and bright sky dotted with white sails. The scene fuses leisure and the <strong>modern sublime</strong>, making perception itself the subject <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The House of the Hanged Man

Paul Cézanne (1873)

Paul Cézanne’s The House of the Hanged Man turns a modest Auvers-sur-Oise lane into a scene of <strong>engineered unease</strong> and <strong>structural reflection</strong>. Jagged roofs, laddered trees, and a steep path funnel into a narrow, shadowed V that withholds a center, making absence the work’s gravitational force. Cool greens and slate blues, set in blocky, masoned strokes, build a world that feels both solid and precarious.

The Japanese Footbridge

Claude Monet (1899)

Claude Monet’s The Japanese Footbridge turns his Giverny garden into an <strong>immersive field of perception</strong>: a pale blue-green arc spans water crowded with lilies, while grasses and willows dissolve into vibrating greens. By eliminating the sky and anchoring the scene with the bridge, Monet makes <strong>reflection, passage, and time</strong> the picture’s true subjects <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Skiff (La Yole)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1875)

In The Skiff (La Yole), Pierre-Auguste Renoir stages a moment of modern leisure on a broad, vibrating river, where a slender, <strong>orange skiff</strong> cuts across a field of <strong>cool blues</strong>. Two women ride diagonally through the shimmer; an <strong>oar’s sweep</strong> spins a vortex of color as a sailboat, villa, and distant bridge settle the scene on the Seine’s suburban edge <sup>[1]</sup>. Renoir turns motion and light into a single sensation, using a high‑chroma, complementary palette to fuse human pastime with nature’s flux <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Swing

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1876)

Renoir’s The Swing fixes a fleeting, sun-dappled exchange in a Montmartre garden, where a woman in a white dress with blue bows steadies herself on a swing while a man in a blue jacket addresses her. The scene crystallizes <strong>modern leisure</strong>, <strong>flirtation</strong>, and <strong>optical shimmer</strong>, as broken strokes scatter light over faces, fabric, and ground <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

The Tub

Edgar Degas (1886)

In The Tub (1886), Edgar Degas turns a routine bath into a study of <strong>modern solitude</strong> and <strong>embodied labor</strong>. From a steep, overhead angle, a woman kneels within a circular basin, one hand braced on the rim while the other gathers her hair; to the right, a tabletop packs a ewer, copper pot, comb/brush, and cloth. Degas’s layered pastel binds skin, water, and objects into a single, breathing field of <strong>warm flesh tones</strong> and blue‑greys, collapsing distance between body and still life <sup>[1]</sup>.

Vase of Flowers

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (c. 1889)

Vase of Flowers is a late‑1880s still life in which Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a humble blue‑green jug and a tumbling bouquet into a <strong>laboratory of color and touch</strong>. Against a warm ocher wall and reddish tabletop, coral and vermilion blossoms flare while cool greens and violets anchor the mass, letting <strong>color function as drawing</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>. The work affirms Renoir’s belief that flower painting was a space for bold experimentation that fed his figure art.

Woman with a Parasol

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s Woman with a Parasol fixes a breezy hillside instant in high, shifting light, setting a figure beneath a <strong>green parasol</strong> against a vast, vibrating sky. The low vantage and <strong>broken brushwork</strong> merge dress, clouds, and grasses into one atmosphere, while a child at the rise anchors depth and intimacy <sup>[1]</sup>. It is a manifesto of <strong>plein-air</strong> perception—painting the sensation of air in motion rather than the contours of things <sup>[2]</sup>.

Related Themes

Within European art since the nineteenth century, nature ceases to be a passive backdrop and emerges as an active semiotic field: trees, rivers, atmospheric veils, and cultivated clearings carry codified meanings about harmony, threat, modernity, and perception. The symbols gathered under the rubric of “Nature” in this collection record that transition with particular clarity. They show how motifs inherit pastoral and classical associations while being retooled by Impressionist and Post‑Impressionist practice into instruments for thinking about time, social order, and the instability of appearances.

Several key motifs stage nature as an ordering, almost architectural presence. In Paul Cézanne’s Bathers, the natural vault of trees is more than a descriptive canopy. Converging trunks and branches organize the scene as a kind of open‑air nave, converting foliage into a pseudo‑architectural space of ritual. Semiotic force lies in this analogy: the grove recalls older Arcadian imagery, yet its “architecture” is constructed through Cézanne’s geometric brushwork rather than linear perspective. The circle/frieze of bathers beneath this vault reinforces the reading. Bodies act as structural piers, a human colonnade that parallels the trees overhead. Nature here is not wild but formalized; it supplies the frame in which communal, quasi‑timeless action occurs, and it does so through a calibrated interplay of figure and ground that makes the very idea of order the painting’s subject.

A related but distinct emphasis on nature’s structuring role appears in Vincent van Gogh’s Irises. The blue‑violet irises themselves signify “collective vitality and rhythmic variation,” but that vitality is inseparable from the ocher soil paths that break the mass of growth. Van Gogh crops in close so that the bed becomes an all‑over field of repeated organic forms. Within this field, the soil bands function both compositionally and symbolically: they are moments of pause, “grounding” breath within abundance, and they reiterate the agricultural context that underlies the work’s spiritual aspirations. The irises’ rhythm thus plays against the tessellation of paths and earth, prefiguring the more overtly geometric tessellated fields and the Mont Sainte‑Victoire summit in Cézanne’s landscapes. In each case, nature provides an armature that holds perception steady, a counterweight to the fugitive character of light and mood.

In Claude Monet’s serial works, Nature symbolism turns toward atmosphere and optical flux. The Haystacks Series stages grainstacks—traditional emblems of rural labor and stored fertility—as temporary monuments whose meaning is suspended within changing light. The stacks themselves stand for “stored grain; symbols of rural labor, fertility, and sustenance,” yet Monet persistently subjects them to sunset’s horizon blaze and chromatic vibration. The setting sun between two mounds functions as a kind of temporal register: a luminous gap where permanence (the harvest) is qualified by the brevity of a particular evening. The symbol of agrarian stability is thus semiotically doubled by the symbol of transience. Light, not object, is the ultimate referent. The same logic governs Houses of Parliament, where a national monument becomes a compressed silhouette within a “silvery enveloppe of haze.” Here the river’s shimmering water reflections are crucial: they transpose architecture into broken rectangles of color, insisting that political authority reaches the viewer only after being filtered through weather, pollution, and time.

Monet’s La Grenouillère elaborates this atmospheric semiotics within a space of modern leisure. The Seine itself, identified symbolically as “flow, stability, and the city’s lifeline,” supports a network of more specific nature motifs: shimmering water / broken color and rippling water and reflections are explicitly tied to “perception and sensation made visible” and to “fluid modern perception and transience.” The floating platform and rental boats are the ostensible subject, but the painting’s true iconography of nature lies in the surface of the water. Broken strokes on the river make visible the instability of social relations in this new leisure culture: class mingling among bathers and strollers is mirrored by the continual recomposition of reflections. Nature here is not Arcadian stasis but a medium of flux in which modern life momentarily suspends itself.

This emphasis on flux is developed further in Monet’s urban nature. In Gare Saint‑Lazare, clouds of steam/smoke explicitly replace traditional clouds: “industrial exhaust transformed into luminous atmosphere; flux, transition, and the ephemerality of modern experience.” Semiotic inversion is at work. Where a Romantic sky might articulate transcendence or divine order, the station’s vaporized air records industrial temporality—trains arriving and departing, schedules, standardized time. Yet the visual rhetoric is continuous with landscape art: steam occupies “the very place a sky would be,” and the shed becomes a surrogate cliff or mountain face. Nature’s role as the guarantor of sublimity is ceded to manufactured atmosphere, but the symbolic grammar—vertical supports, receding vault, luminous haze—remains recognizable.

Other works in the group explore nature as a gently moralized or psychologized environment. Pierre‑Auguste Renoir’s Girl with a Watering Can inhabits a bourgeois garden whose dappled foliage and light “signify outdoor freedom and Impressionist luminosity.” The lawn and shrubs dissolve into flickering strokes that assert time‑bound perception; against this, the child’s solid modeling and the green can align nurture and growth with a specifically cultivated nature. The garden is neither wild nor sublime; it is controlled fertility, a domesticized Arcadia in which the symbolism of water—renewal, care, the promise of future bloom—is quietly folded into modern childhood. Nature, here, functions as an ethical surround, articulating ideals of innocence and proper cultivation.

Camille Pissarro’s Red Roofs offers a more systemic integration of settlement and landscape. His screen of winter trees and broader leafless winter trees create a “lattice that filters vision,” mediating between viewer and village. Semiologically, these bare branches mark the seasonal cycle—life in dormancy—while also providing a graphic grid that parallels the urban plan. The chromatic echoes that bind roofs to fields underscore the symbol’s thrust: human dwelling is not opposed to nature but woven into its pattern. This image of nature as grid anticipates the more abstract “tessellated fields” in Cézanne’s Mont Sainte‑Victoire, where cultivated parcels become modular planes organizing the valley. In both, nature is not merely observed; it is constructed as a system of relations, the visible analogue of social and pictorial order.

Across these examples, the Nature symbols form a web of connections. The natural vault of trees in Cézanne’s Bathers answers the architectural silhouette of Westminster or Rouen in Monet’s serial works; in each case, a vertical mass—foliage or stone—anchors atmospheric flux. The shimmering water of the Seine at La Grenouillère echoes the Thames’s shimmering water reflections at Westminster; surface vibration becomes the modern equivalent of the classical river god, a personification not in bodily form but in optical behavior. Even the humble ocher soil paths in Irises rhyme structurally with the banded horizons of Manet’s On the Beach, where the “banded, high‑horizon sea” likewise converts depth into flat registers, asserting nature as a set of stacked fields of experience rather than a stable stage.

Historically, these symbols trace a shift from nature as the site of mythic narratives or moral allegory toward nature as an epistemological problem: how do we see, and how is seeing shaped by time, industry, and social life? The Arcadian natural vault and pastoral streams of earlier traditions persist, but they are reinterpreted through Impressionist optics and modern subjectivities. Trees become scaffolds; rivers become mirrors of perception; haze and steam, whether natural or industrial, become the primary carriers of meaning. By the time of Monet’s late serial works and Cézanne’s constructive landscapes, Nature symbolism has largely migrated from discrete iconographic emblems (a particular tree, a specific flower) to fields of color and atmosphere that stand for transience, continuity, and the very act of witnessing change.