Domesticity

The “Domesticity” symbolism category traces how modern artists transform humble household objects, routines, and furnishings into a complex visual language of labor, intimacy, and psychological tension within the home and its adjacent social spaces.

Member Symbols

Featured Artworks

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

Édouard Manet (1882)

Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère stages a face-to-face encounter with modern Paris, where <strong>commerce</strong>, <strong>spectacle</strong>, and <strong>alienation</strong> converge. A composed barmaid fronts a marble counter loaded with branded bottles, flowers, and a brimming bowl of oranges, while a disjunctive <strong>mirror</strong> unravels stable viewing and certainty <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Dance in the Country

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

Dance in the Country shows a couple swept into a close embrace on a café terrace, their bodies turning in a soft spiral as foliage and sunlight dissolve into <strong>dappled color</strong>. Renoir orchestrates <strong>bourgeois leisure</strong>—the tossed straw boater, a small table with glass and napkin, the woman’s floral dress and red bonnet—to stage a moment where decorum and desire meet. The result is a modern emblem of shared pleasure, poised between Impressionist shimmer and a newly <strong>firm, linear touch</strong>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town

Camille Pissarro (1879)

In Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town, two working women strain under <strong>white bundles</strong> that flare against a <strong>flat yellow ground</strong> and a <strong>dark brown band</strong>. The abrupt cropping and opposing diagonals turn anonymous labor into a <strong>monumental, modern frieze</strong> of effort and motion.

Plum Brandy

Édouard Manet (ca. 1877)

Manet’s Plum Brandy crystallizes a modern pause—an urban <strong>interval of suspended action</strong>—through the idle tilt of a woman’s head, an <strong>unlit cigarette</strong>, and a glass cradling a <strong>plum in amber liquor</strong>. The boxed-in space—marble table, red banquette, and decorative grille—turns a café moment into a stage for <strong>solitude within public life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

Portrait of Dr. Gachet distills Van Gogh’s late ambition for a <strong>modern, psychological portrait</strong> into vibrating color and touch. The sitter’s head sinks into a greenish hand above a <strong>blazing orange-red table</strong>, foxglove sprig nearby, while waves of <strong>cobalt and ultramarine</strong> churn through coat and background. The chromatic clash turns a quiet pose into an <strong>empathic image of fragility and care</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Summer's Day

Berthe Morisot (about 1879)

Two women drift on a boat in the Bois de Boulogne, their dresses, hats, and a bright blue parasol fused with the lake’s flicker by Morisot’s swift, <strong>zig‑zag brushwork</strong>. The scene turns a brief outing into a poised study of <strong>modern leisure</strong> and <strong>female companionship</strong> in public space <sup>[1]</sup>.

Sunflowers

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is a <strong>yellow-on-yellow</strong> still life that stages a full <strong>cycle of life</strong> in fifteen blooms, from fresh buds to brittle seed heads. The thick impasto, green shocks of stem and bract, and the vase signed <strong>“Vincent”</strong> turn a humble bouquet into an emblem of endurance and fellowship <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Artist's Garden at Vétheuil

Claude Monet (1881)

Claude Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil stages a sunlit ascent through a corridor of towering sunflowers toward a modest house, where everyday life meets cultivated nature. Quick, broken strokes make leaves and shadows tremble, asserting <strong>light</strong> and <strong>painterly surface</strong> over linear contour. Blue‑and‑white <strong>jardinieres</strong> anchor the foreground, while a child and dog briefly pause on the path, turning the garden into a <strong>domestic sanctuary</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

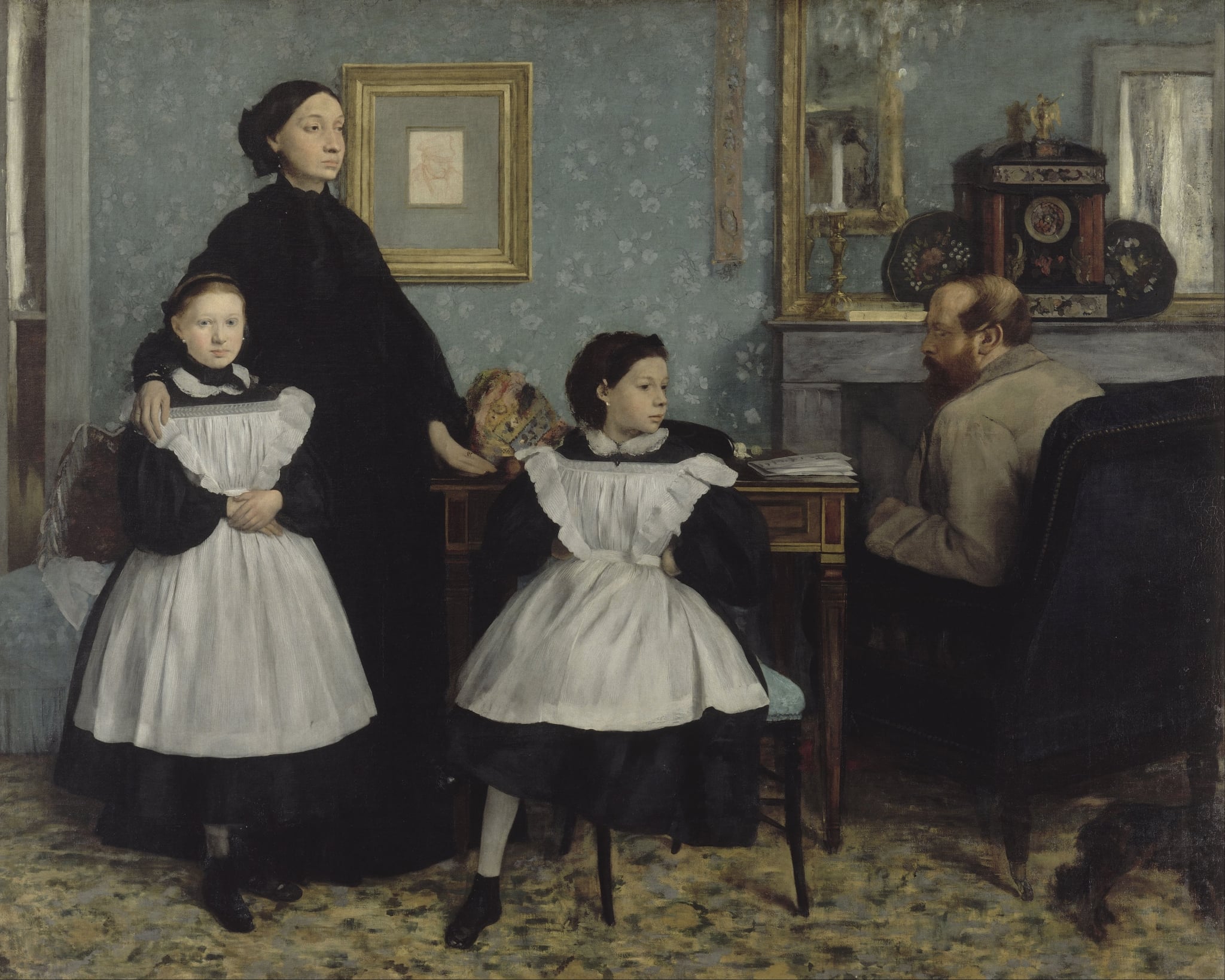

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Card Players by Paul Cézanne | Equilibrium and Form

Paul Cézanne

In The Card Players, Paul Cézanne turns a rural café game into a study of <strong>equilibrium</strong> and <strong>monumentality</strong>. Two hated peasants lean inward across an orange-brown table while a dark bottle stands upright between them, acting as a calm, vertical <strong>axis</strong> that stabilizes their mirrored focus <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Child's Bath

Mary Cassatt (1893)

Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (1893) recasts an ordinary ritual as <strong>modern devotion</strong>. From a steep, print-like vantage, interlocking stripes, circles, and diagonals focus attention on <strong>touch, care, and renewal</strong>, turning domestic labor into a subject of high art <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The work synthesizes Impressionist sensitivity with <strong>Japonisme</strong> design to monumentalize the private sphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Floor Scrapers

Gustave Caillebotte (1875)

Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers stages three shirtless workers planing a parquet floor as shafts of light pour through an ornate balcony door. The painting fuses <strong>rigorous perspective</strong> with <strong>modern urban labor</strong>, turning curls of wood and raking light into a ledger of time and effort <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. Its cool, gilded interior makes visible how bourgeois elegance is built on bodily work.

The Loge

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Loge (1874) turns an opera box into a <strong>stage of looking</strong>, where a woman meets our gaze while her companion scans the crowd through binoculars. The painting’s <strong>frame-within-a-frame</strong> and glittering fashion make modern Parisian leisure both alluring and self-conscious, turning spectators into spectacles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Railway

Édouard Manet (1873)

Manet’s The Railway is a charged tableau of <strong>modern life</strong>: a composed woman confronts us while a child, bright in <strong>white and blue</strong>, peers through the iron fence toward a cloud of <strong>steam</strong>. The image turns a casual pause at the Gare Saint‑Lazare into a meditation on <strong>spectatorship, separation, and change</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Tub

Edgar Degas (1886)

In The Tub (1886), Edgar Degas turns a routine bath into a study of <strong>modern solitude</strong> and <strong>embodied labor</strong>. From a steep, overhead angle, a woman kneels within a circular basin, one hand braced on the rim while the other gathers her hair; to the right, a tabletop packs a ewer, copper pot, comb/brush, and cloth. Degas’s layered pastel binds skin, water, and objects into a single, breathing field of <strong>warm flesh tones</strong> and blue‑greys, collapsing distance between body and still life <sup>[1]</sup>.

Woman at Her Toilette

Berthe Morisot (1875–1880)

Woman at Her Toilette stages a private ritual of self-fashioning, not a spectacle of vanity. A woman, seen from behind, lifts her arm to adjust her hair as a <strong>black velvet choker</strong> punctuates Morisot’s silvery-violet haze; the <strong>mirror’s blurred reflection</strong> with powders, jars, and a white flower refuses a clear face. Morisot’s <strong>feathery facture</strong> turns a fleeting toilette into modern subjectivity made visible <sup>[1]</sup>.

Woman Ironing

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1887)

In Woman Ironing, Degas builds a modern icon of labor through <strong>contre‑jour</strong> light and a forceful diagonal from shoulder to iron. The worker’s silhouette, red-brown dress, and the cool, steamy whites around her turn repetition into <strong>ritualized transformation</strong>—wrinkled cloth to crisp order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman Reading

Édouard Manet (1880–82)

Manet’s Woman Reading distills a fleeting act into an emblem of <strong>modern self-possession</strong>: a bundled figure raises a journal-on-a-stick, her luminous profile set against a brisk mosaic of greens and reds. With quick, loaded strokes and a deliberately cropped <strong>beer glass</strong> and paper, Manet turns perception itself into subject—asserting the drama of a private mind within a public café world <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Young Girls at the Piano

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892)

Renoir’s Young Girls at the Piano turns a quiet lesson into a scene of <strong>attunement</strong> and <strong>bourgeois grace</strong>. Two adolescents—one seated at the keys, the other leaning to guide the score—embody harmony between discipline and delight, rendered in Renoir’s late, <strong>luminous</strong> touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Related Themes

Related Symbolism Categories

Objects

In modern painting, everyday objects become charged mediators of vision, labor, desire, and time, replacing inherited allegories with a material, self-conscious language of modern life.

Objecthood

The “Objecthood” symbolism category traces how seemingly ordinary implements—bottles, clocks, mirrors, gloves, café tableware—become charged mediators of labor, time, spectacle, and selfhood in modern painting, shifting from stable attributes to critical signs of fractured, commodity-driven experience.

Vision

“Vision” symbols in modern painting mark not only what is seen but how seeing itself becomes a historical, technological, and psychological problem, turning light, reflection, and vantage into active agents of meaning.

Within the broad history of genre and interior painting, the symbolism of domesticity marks a decisive shift from the moralized household scenes of early modern art to the more ambiguous, psychologically freighted interiors of the nineteenth century. Where seventeenth‑century Dutch painters, for instance, often cast the home as a stage for virtue or vice in clearly legible allegories, later artists used ordinary furnishings, tools, and rituals to register subtler tensions between labor and leisure, privacy and publicity, care and commodification. In this modern idiom, the domestic is less a fixed sphere than a field of negotiation, and the smallest object—a jug, a towel, a chair, a basin—can function as a node where social roles, gendered work, and emotional states intersect.

Viewed semiotically, these domestic symbols operate as a tightly knit system of signs that derive meaning from their relations as much as from their individual identities. The white ewer and pitcher condense the idea of stored water and preparedness for washing, while the basin of water and white towel or cloth mark the threshold where soiling becomes cleanliness. Together, they structure a ritual sequence—supply, act, and transition—that elevates everyday hygiene into a visual language of care. In Mary Cassatt’s The Child’s Bath (invoked in the basin’s definition), this sequence becomes a compositional engine: the interlocking circles of basin and jug, the diagonals of striped textiles, and the concentration of touch around the caregiver’s hands convert domestic tending into a serious pictorial subject. The basin anchors the scene as a humble altar of renewal, while the towel mediates between wet and dry, nakedness and modesty, function and affection.

Other works in the corpus reveal how domestic emblems can press beyond the private home into semi‑public interiors. In Manet’s Plum Brandy, domesticity is displaced into the regulated comfort of a café, yet many of the same structural functions persist. The marble café table supplies a hard, impersonal horizontal akin to a kitchen or dining table, a surface where objects and gestures are staged and judged. On it sit the glass with plum brandy and the unlit cigarette—small tokens of after‑meal or after‑work repose that echo, in a displaced key, the ritual punctuation marked elsewhere by coffee cups and saucers or the small liqueur glass. Here, however, the drink’s meaning is inverted: it is “sweet indulgence held in reserve; consumption deferred,” and the entire drama of the painting lies in that suspension. Domestic habit—the rhythm of ingestion and rest—is recast as urban lassitude, the subject’s head cradled in her hand as if the café were a substitute parlour, her solitude framed by the red banquette that both cushions and confines.

Renoir’s Dance in the Country similarly reconfigures domestic signs within a public or semi‑public setting. The small table with decanter, glass, cup, and cloth at the dancers’ side registers the after‑meal ritual of refinement and sociability, even as the couple has already left it behind. The sequence wine–coffee–liqueur–smoke—crystallized in the small liqueur glass and the accompanying accessories—sketches a familiar bourgeois pattern that might equally unfold in a salon. Yet here it takes place on a café terrace, where the home’s convivial codes are performed under the gaze of others. The woman’s long yellow gloves, explicitly linked to etiquette at public dances, bridge the domestic and the civic by making physical intimacy socially acceptable. What in a private interior would be an unremarkable touch becomes, in this context, a carefully mediated form of contact, governed by accessories as much as by feeling.

That principle of mediation extends to the threshold between interior and exterior, a zone where domestic cultivation literally crosses the house’s walls. Monet’s The Artist’s Garden at Vétheuil hinges on potted plants and jardinieres that translate the order of the home into the open air; they are containers of managed life, aligning horticultural care with household discipline. The child and small dog on the path further signal that this is not a purely decorative garden but a lived one, in which domestic continuity and companionship animate the space. Within this setting, the blocky houses in the distance read not as picturesque architecture but as cubic volumes—human presence as structure—into which the intimate routines of washing, tending, and resting retreat.

Degas’s The Bellelli Family offers a more fraught interior, where domestic objects become sharp signifiers of hierarchy and distance. The gilt mantel clock embodies not only time and routine but the “pressure of domestic order/status,” presiding over a room in which relationships are already strained. The clock’s gilded casing, together with the rigid furniture, anchors a world of inherited roles; its steady ticking contrasts with the emotional stasis of the sitters. To the right, the father’s desk with papers as barrier marks his participation in an outward, professional sphere, materially and spatially separating him from wife and daughters. The desk literalizes the divide between public work and private life, while the daughters—positioned between clock and desk—mediate those poles. Here, domesticity is not softness but structure; its symbols codify the very tensions they ostensibly organize.

If Degas and Monet use domestic signs to articulate social architecture, Pissarro (as described in Laundresses Carrying Linen in Town) pushes the same vocabulary toward labor and class. The white linen bundles on the laundresses’ shoulders embody “the paradox of cleanliness produced through hard labor; the weight of work made visible.” Linen, which in the bourgeois interior would appear as the crisp white towel or white linen and steam of ironing, here returns as burden, its purity achieved through bodily strain rather than quietly assumed as a neutral backdrop to family life. The flat yellow ground and dark band eliminate anecdotal detail, so that these domestic textiles become the very measure of urban work, foreshadowing later social realist uses of household materials as indices of exploitation.

Running through these examples is a persistent interplay between containment and release, stability and instability, that domestic symbols help to stage. Tables and chairs—whether the crimson armchair in Cézanne’s portrait of Madame Cézanne, the empty wooden chair in other interiors, or the boxed‑in banquette of Manet’s café—operate as structural masses that stabilize figures even as they hint at pressure or absence. Vessels such as the crackled porcelain vase or the signed earthenware vase reconcile permanence and fragility, pairing enduring craft with wilting flowers or personal welcome. The footed compote elevating oranges in Cézanne’s still lifes, with its slight forward lean, introduces a controlled instability that mirrors the delicately balanced economies and relationships enacted around domestic tables.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, these domestic symbols were progressively reinterpreted. What once functioned in earlier art as relatively stable emblems of virtue, order, or feminine sphere became, in the hands of Manet, Degas, Cassatt, Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh, and Pissarro, dynamic instruments for probing modern subjectivity. The kitchen and parlour, the garden and café, merge into a continuum, where objects shuttle between home and public venue and meanings are no longer fixed in moral codes but negotiated through framing, facture, and color. A basin or towel might still signify care and renewal, but it also indexes gendered labor; a clock charts not just routine, but the slow strain of familial duty; a glass left on a café table traces the fragile overlap between domestic habit and urban sociability. In this modern register, domesticity is not merely a setting but a symbolic matrix through which artists think pictorially about time, class, desire, and the precarious equilibria of everyday life.