Identity

The Identity symbolism category traces how modern and contemporary artists mobilize poses, accessories, and gazes as semiotic devices that construct, fracture, and negotiate personhood within evolving social and urban regimes.

Member Symbols

Featured Artworks

A Bar at the Folies-Bergère

Édouard Manet (1882)

Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère stages a face-to-face encounter with modern Paris, where <strong>commerce</strong>, <strong>spectacle</strong>, and <strong>alienation</strong> converge. A composed barmaid fronts a marble counter loaded with branded bottles, flowers, and a brimming bowl of oranges, while a disjunctive <strong>mirror</strong> unravels stable viewing and certainty <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

At the Moulin Rouge

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1892–1895)

At the Moulin Rouge plunges us into the churn of Paris nightlife, staging a crowded room where spectacle and fatigue coexist. A diagonal banister and abrupt croppings create <strong>off‑kilter immediacy</strong>, while harsh artificial light turns faces <strong>masklike</strong> and cool. Mirrors multiply the crowd, amplifying a mood of allure tinged with <strong>urban alienation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Dance at Bougival

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

In Dance at Bougival, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a crowded suburban dance into a <strong>private vortex of intimacy</strong>. Rose against ultramarine, skin against shade, and a flare of the woman’s <strong>scarlet bonnet</strong> concentrate the scene’s energy into a single turning moment—modern leisure made palpable as <strong>touch, motion, and light</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Dance in the City

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance in the City stages an urban waltz where decorum and desire briefly coincide. A couple’s close embrace—his black tailcoat enclosing her luminous white satin gown—creates a <strong>cool, elegant</strong> harmony against potted palms and marble. Renoir’s refined, post‑Impressionist touch turns social ritual into <strong>sensual modernity</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Jane Avril

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (c. 1891–1892)

In Jane Avril, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec crystallizes a public persona from a few <strong>urgent, chromatic strokes</strong>: violet and blue lines whirl into a cloak, while green and indigo dashes crown a buoyant hat. Her face—sharply keyed in <strong>lemon yellow, lilac, and carmine</strong>—hovers between mask and likeness, projecting poise edged with fatigue. The raw brown ground lets her <strong>whiplash silhouette</strong> materialize like smoke from Montmartre’s nightlife.

Luncheon on the Grass

Édouard Manet (1863)

Luncheon on the Grass stages a confrontation between <strong>modern Parisian leisure</strong> and <strong>classical precedent</strong>. A nude woman meets our gaze beside two clothed men, while a distant bather and an overturned picnic puncture naturalistic illusion. Manet’s scale and flat, studio-like light convert a park picnic into a manifesto of <strong>modern painting</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair

Paul Cézanne (about 1877)

Paul Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair (about 1877) turns a domestic sit into a study of <strong>color-built structure</strong> and <strong>compressed space</strong>. Cool blue-greens of dress and skin lock against the saturated <strong>crimson armchair</strong>, converting likeness into an inquiry about how painting makes stability visible <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Olympia

Édouard Manet (1863 (Salon 1865))

A defiantly contemporary nude confronts the viewer with a steady gaze and a guarded pose, framed by crisp light and luxury trappings. In Olympia, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> strips myth from the female nude to expose the <strong>modern economy of desire</strong>, power, and looking <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

Portrait of Dr. Gachet distills Van Gogh’s late ambition for a <strong>modern, psychological portrait</strong> into vibrating color and touch. The sitter’s head sinks into a greenish hand above a <strong>blazing orange-red table</strong>, foxglove sprig nearby, while waves of <strong>cobalt and ultramarine</strong> churn through coat and background. The chromatic clash turns a quiet pose into an <strong>empathic image of fragility and care</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Beach at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet (1867)

In The Beach at Sainte-Adresse, Claude Monet stages a modern shore where <strong>labor and leisure intersect</strong> under a broad, changeable sky. The bright <strong>blue beached boat</strong> and the flotilla of <strong>rust-brown working sails</strong> punctuate a turquoise channel, while a fashionably dressed pair sits mid-beach, spectators to the traffic of the port. Monet’s brisk, broken strokes make the scene feel <strong>caught between tides and weather</strong>, a momentary balance of work, tourism, and atmosphere <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

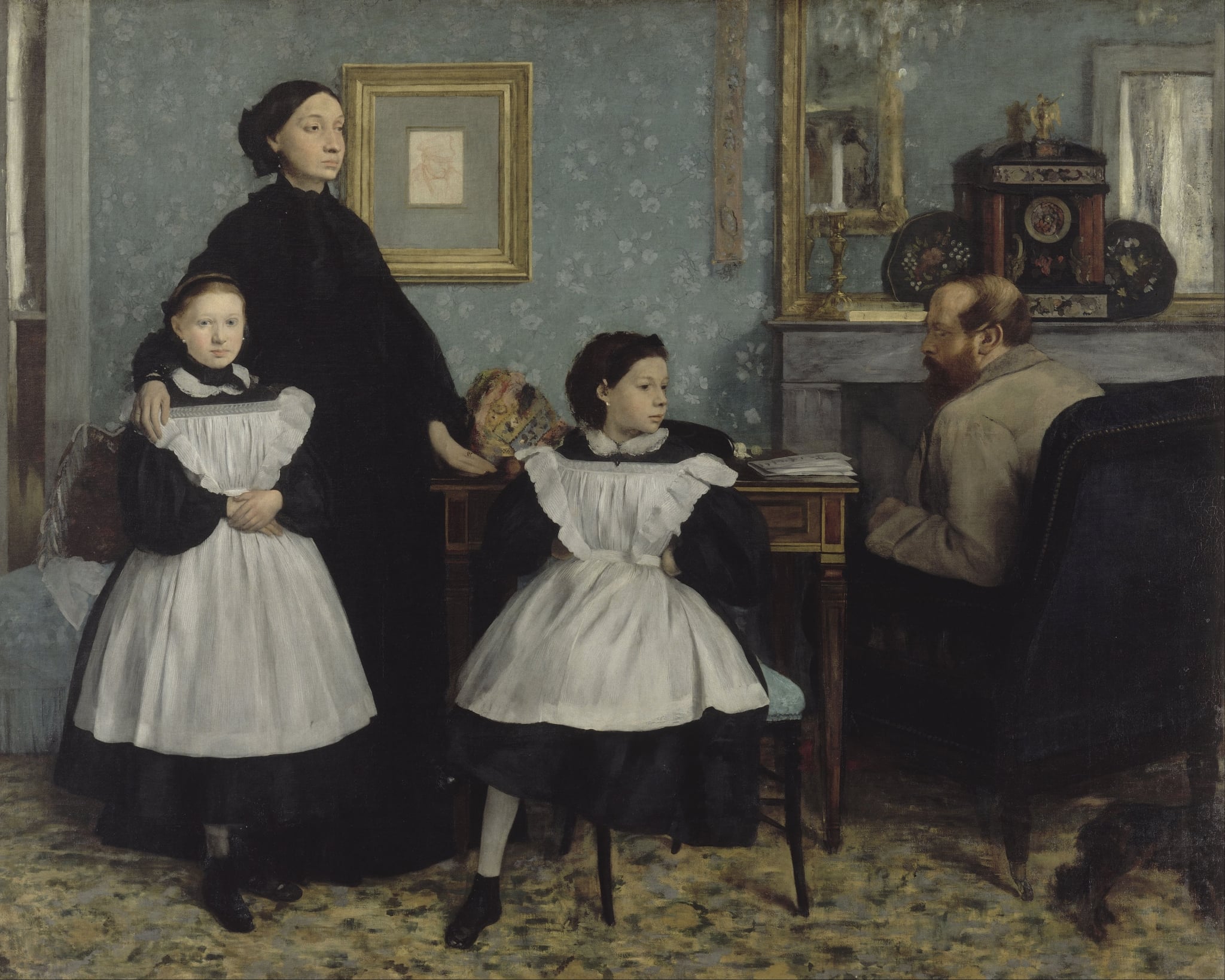

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Boating Party

Mary Cassatt (1893–1894)

In The Boating Party, Mary Cassatt fuses <strong>intimate caregiving</strong> with <strong>modern mobility</strong>, compressing mother, child, and rower inside a skiff that cuts diagonals across ultramarine water. Bold arcs of citron paint and a high, flattened horizon reveal a deliberate <strong>Japonisme</strong> logic that stabilizes the scene even as motion surges around it <sup>[1]</sup>. The painting asserts domestic life as a public, modern subject while testing the limits of Impressionist space and color.

The Cradle

Berthe Morisot (1872)

Berthe Morisot’s The Cradle turns a quiet nursery into a scene of <strong>vigilant love</strong>. A gauzy veil, lifted by the watcher’s hand, forms a <strong>protective boundary</strong> that cocoons the sleeping child in light while linking the two figures through a decisive diagonal <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The painting crystallizes modern maternity as a form of attentiveness rather than display—an <strong>unsentimental icon</strong> of care.

The Fifer

Édouard Manet (1866)

In The Fifer, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> monumentalizes an anonymous military child by isolating him against a flat, gray field, converting everyday modern life into a subject of high pictorial dignity. The crisp <strong>silhouette</strong>, blocks of <strong>unmodulated color</strong> (black tunic, red trousers, white gaiters), and glints on the brass case make sound and discipline palpable without narrative scaffolding <sup>[1]</sup>. Drawing on <strong>Velázquez’s single-figure-in-air</strong> formula yet inflected by japonisme’s flatness, Manet forges a new modern image that the Salon rejected in 1866 <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Harbour at Lorient

Berthe Morisot (1869)

Berthe Morisot’s The Harbour at Lorient stages a quiet tension between <strong>private reverie</strong> and <strong>public movement</strong>. A woman under a pale parasol sits on the quay’s stone lip while a flotilla of masted boats idles across a silvery basin, their reflections dissolving into light. Morisot’s <strong>pearly palette</strong> and brisk brushwork make the water read as time itself, holding stillness and departure in the same breath <sup>[1]</sup>.

Woman at Her Toilette

Berthe Morisot (1875–1880)

Woman at Her Toilette stages a private ritual of self-fashioning, not a spectacle of vanity. A woman, seen from behind, lifts her arm to adjust her hair as a <strong>black velvet choker</strong> punctuates Morisot’s silvery-violet haze; the <strong>mirror’s blurred reflection</strong> with powders, jars, and a white flower refuses a clear face. Morisot’s <strong>feathery facture</strong> turns a fleeting toilette into modern subjectivity made visible <sup>[1]</sup>.

Woman Reading

Édouard Manet (1880–82)

Manet’s Woman Reading distills a fleeting act into an emblem of <strong>modern self-possession</strong>: a bundled figure raises a journal-on-a-stick, her luminous profile set against a brisk mosaic of greens and reds. With quick, loaded strokes and a deliberately cropped <strong>beer glass</strong> and paper, Manet turns perception itself into subject—asserting the drama of a private mind within a public café world <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Young Girls at the Piano

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1892)

Renoir’s Young Girls at the Piano turns a quiet lesson into a scene of <strong>attunement</strong> and <strong>bourgeois grace</strong>. Two adolescents—one seated at the keys, the other leaning to guide the score—embody harmony between discipline and delight, rendered in Renoir’s late, <strong>luminous</strong> touch <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Related Themes

Related Symbolism Categories

Fashion

In Impressionist and related modern painting, fashion functions as a coded system of class, gender, and spectatorship, translating older allegorical and mythic meanings into the language of couture, accessories, and regulated bodily comportment.

Objects

In modern painting, everyday objects become charged mediators of vision, labor, desire, and time, replacing inherited allegories with a material, self-conscious language of modern life.

Body

The body symbolism of modern painting transforms gestures, gazes, costumes, and fragmentary viewpoints into a precise language through which artists negotiate desire, labor, spectatorship, and interiority in an increasingly commodified visual culture.

Within Western art, identity has rarely been a given; it is made visible, and thus debatable, through a dense repertoire of signs. From allegorical personifications such as Liberty to the cropped, masklike faces of modern nightlife, artists have relied on recurrent motifs—gestures, clothing, accessories, vantage points—to stage the self as a constructed, historically situated phenomenon. The symbols gathered under the category of “Identity” do not merely record individual likeness; they articulate how subjects are positioned in relation to power, desire, class, and spectatorship. In the long arc from classical allegory to the disquieting physiognomies of Parisian modernity, identity emerges less as essence than as an effect of representation.

Semiotically, these motifs function as compact signifiers within complex visual systems. Some are overtly allegorical, such as Allegorical Liberty (Marianne), whose Phrygian cap, tricolour palette, and forward-striding pose encode the French Republic and a collective ideal of popular agency. She is less an individual than an avatar of civic subjecthood, synthesizing national identity into a single, mobilizing figure. Others operate at a more intimate scale, like the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait: a framed image within the image that invokes lineage, memory, and inherited obligation. Both are, in Peircean terms, indices of relation rather than of interior psychology: Marianne ties the subject to the polity; the ancestral portrait ties it to the family line.

By the later nineteenth century, such explicit allegories coexist with a more fractured, urban iconography of selfhood. In Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, the barmaid Suzon is structured as a hinge between commodity and person. The symbol of the Barmaid (Suzon) encapsulates this duality: she is the human face of urban commerce, at once salesperson and potential commodity. Positioned frontally behind a marble counter strewn with branded bottles and bright oranges, she meets the viewer with a steady, opaque gaze. This confrontational gaze/frontality pulls us into the transaction while simultaneously blocking access to an interior life. Her identity is overdetermined by the objects that flank her, and further unsettled by the skewed mirror behind: the male customer appears only in reflection, and her reflected body is displaced to the right. Here, identity is refracted through systems of exchange and spectatorship; the barmaid’s persona is legible less as a coherent psychological self than as a nodal point in a network of gazes, commodities, and spatial disjunctions.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec radicalizes this modern condition of constructed identity through chromatic and compositional strategies. In At the Moulin Rouge, several figures bear green-blue, masklike faces. The green-blue, masklike face, produced by harsh artificial light on powdered skin, semiotically displaces the sitter from naturalistic portraiture into the realm of performance and façade. These high-keyed, artificial visages echo the more general category of masklike faces: protective, ritualized surfaces that signal guarded sexuality and a deliberate break from the illusion of unmediated presence. The cabaret’s mirrors, which double and triple the crowd, further undermine stable identity, suggesting instead a proliferation of partial selves and viewpoints. The composition’s oblique angles and cropped bodies contribute to this effect. Cropped and partial bodies signify a modern, off-axis way of seeing; identity is grasped only in fragments, as though glimpsed through a camera or from a passing crowd. In such a context, the “self” appears as an unstable apparition within the culture of spectacle.

Lautrec’s Jane Avril intensifies this interplay between persona and trace. The sitter’s face is again mask-like and high-keyed: lemon yellow, lilac, and carmine model a physiognomy that hovers between likeness and emblem. The green-blue, hat-crowned profile and the whiplash cloak coalesce into a profile silhouette that conveys classical poise and autonomy, yet the raw ground and abbreviated modeling insist on her as a constructed sign. Avril’s public identity is literally drawn with the same graphic economy as an advertising poster. Semiotically, the portrait acknowledges that the performer’s modern subjectivity is assembled from commodities (hat, cloak), lighting, and the viewer’s recognition; the mask is not a concealment of an authentic self but the very form identity takes in a publicity-saturated world.

Other works in this corpus foreground identity as a negotiation between intimacy and social coding. Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s dance scenes juxtapose symbolic dress and gesture to define roles within tightly scripted rituals. In Dance in the City, the man’s black tailcoat encapsulates masculine decorum and formal restraint, framing desire without lapsing into impropriety. Against this dark armature, the woman’s luminous white satin gown functions, in Morisot’s terms, as a seated woman in white dress might: as an emblem of visible propriety and modern interiority. Her profile and the regulated touch—gloved hand on the man’s shoulder—construct a persona in which sensuality is authorized only through adherence to codes of high-bourgeois respectability. Identity here is inseparable from costume; the garments are not mere description but iconographic instruments that position the couple within an urban, elite milieu.

Dance at Bougival replays this logic in a more informal setting. The man’s dark jacket and the woman’s swirling, pale dress again configure complementary roles, but the crucial symbol is their clasped, ungloved hands. Unprotected touch in a public dance space marks a more direct, bodily intimacy, a temporary suspension of decorum. Yet the surrounding witnesses at the edge, faintly indicated figures and traces of a crowd, frame this intimacy within social observation. These unnamed onlookers underscore that identity in such scenes is always doubled: one is both experiencing subject and spectacle for others, an ambivalence that runs through modern representations of leisure.

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day extends this logic from individual to type. The central bourgeois couple (flâneur and companion) crystallizes middle-class urban identity as a matter of carriage, dress, and spatial comportment. His top hat and tailored black overcoat, her fitted, modest dress, together form a moving silhouette of public decorum and detached observation. They exemplify the flâneur’s role as spectator of the modern city, yet their anonymity—faces generalized, expressions unreadable—signals the averted, shadowed faces of typified labor and class: they are emblems rather than case studies. The painting’s photographic croppings, such as the abruptly truncated figure at the right margin, reinforce a sense in which persons are subject to the logic of the frame, caught as passing fragments within the urban order.

Across these examples, certain symbols enter into a shared semantic field. The masklike face, the frontal barmaid, the bourgeois couple, the uniformed black coat: all articulate identity as a function of social position and systems of looking. Accessories like the black ribbon choker in Manet’s Olympia (explicitly coded as modern, purchasable luxury and contemporary sexuality) or the black velvet choker in Morisot’s toilette scenes condense complex questions of class, gender, and modernity into a single band of pigment encircling the throat. They link the body to the marketplace, to fashion, and to the temporality of trend, reframing subjectivity as an ongoing practice of self-fashioning.

Historically, the trajectory from Allegorical Liberty and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait to Lautrec’s masklike physiognomies and Manet’s barmaid charts a shift from stable, typological identities—citizen, heir, mother—to volatile, performative selves embedded in new structures of urban capitalism and spectacle. Where early modern symbols grounded identity in transcendental ideals or genealogical continuity, late nineteenth-century motifs emphasize mediation, artifice, and fragmentation. The evolution of these icons thus mirrors broader cultural transformations: the rise of mass entertainment, consumer culture, and photographic seeing. In this sense, the “Identity” symbols mapped here not only depict subjects; they offer a historiography of how Western art has imagined what it means to be someone in the world.