Urbanity

Urbanity symbolism in modern painting encodes the redesigned city as both infrastructure and experience, using bridges, boulevards, stations, lamps, and crowds to figure how industrial modernity reorganized vision, movement, and social relations.

Member Symbols

Featured Artworks

Bathers at Asnières

Georges Seurat (1884)

Bathers at Asnières stages a scene of <strong>modern leisure</strong> on the Seine, where workers recline and wade beneath a hazy, unified light. Seurat fuses <strong>classicizing stillness</strong> with an <strong>industrial backdrop</strong> of chimneys, bridges, and boats, turning ordinary rest into a monumental, ordered image of urban life <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The canvas balances soft greens and blues with geometric structures, producing a calm yet charged harmony.

Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Camille Pissarro (1897)

A high window turns Paris into a flowing current: in Boulevard Montmartre at Night, Camille Pissarro fuses <strong>modern light</strong> and <strong>urban movement</strong> into a single, restless rhythm. Cool electric halos and warm gaslit windows shimmer across rain‑slick stone, where carriages and crowds dissolve into <strong>pulse-like blurs</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Gare Saint-Lazare

Claude Monet (1877)

Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare turns an iron-and-glass train shed into a theater of <strong>steam, light, and motion</strong>. Twin locomotives, gas lamps, and a surge of figures dissolve into bluish vapor under the diagonal canopy, recasting industrial smoke as <strong>luminous atmosphere</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Houses of Parliament

Claude Monet (1903)

Claude Monet’s Houses of Parliament renders Westminster as a <strong>dissolving silhouette</strong> in a wash of peach, mauve, and pale gold, where stone and river are leveled by <strong>luminous fog</strong>. Short, vibrating strokes turn architecture into <strong>atmosphere</strong>, while a tiny boat anchors human scale amid the monumental scene.

In the Loge

Mary Cassatt (1878)

Mary Cassatt’s In the Loge (1878) stages modern spectatorship as a drama of <strong>mutual looking</strong>. A woman in dark dress leans forward with <strong>opera glasses</strong>, her <strong>fan closed</strong> on her lap, as a man in the distance raises his own glasses toward her—turning the theater into a circuit of gazes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Paris Street; Rainy Day

Gustave Caillebotte (1877)

Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day renders a newly modern Paris where <strong>Haussmann’s geometry</strong> meets the <strong>anonymity of urban life</strong>. Umbrellas punctuate a silvery atmosphere as a <strong>central gas lamp</strong> and knife-sharp façades organize the space into measured planes <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Pont Neuf Paris

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1872)

In Pont Neuf Paris, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns the oldest bridge in Paris into a stage where <strong>light</strong> and <strong>movement</strong> bind a city back together. From a high perch, he orchestrates crowds, carriages, gas lamps, the rippling Seine, and a fluttering <strong>tricolor</strong> so that everyday bustle reads as civic grace <sup>[1]</sup>.

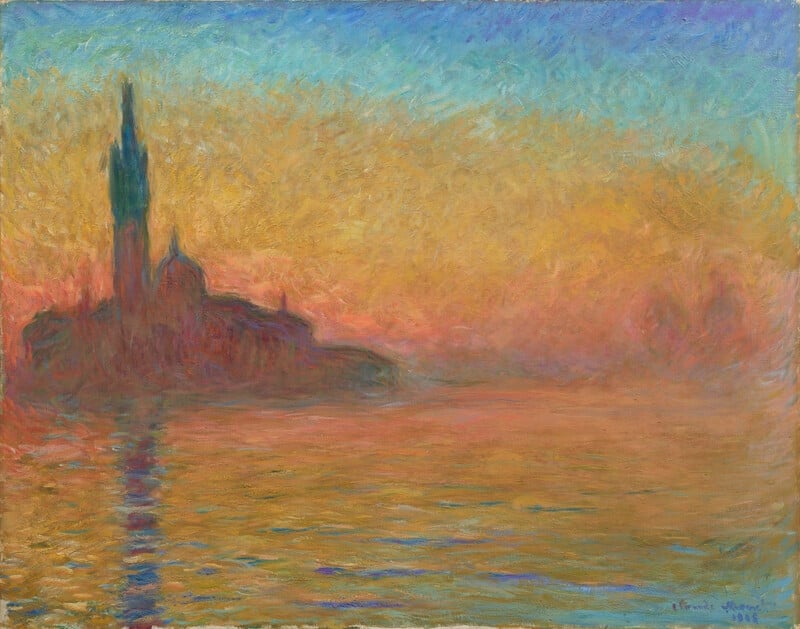

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

Claude Monet (1908–1912)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk fuses the Benedictine church’s dark silhouette with a sky flaming from apricot to cobalt, turning architecture into atmosphere. The campanile’s vertical and its wavering reflection anchor a sea of trembling color, staging a meditation on <strong>permanence</strong> and <strong>flux</strong>.

San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight turns Venice into a <strong>luminous threshold</strong> where stone, air, and water merge. The dark, melting silhouette of the church and its vertical reflection anchor a field of <strong>apricot–rose–violet</strong> light that drifts into cool turquoise, making permanence feel provisional <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet’s subject is not the monument, but the <strong>enveloppe</strong> of atmosphere that momentarily creates it <sup>[4]</sup>.

Snow at Argenteuil

Claude Monet (1875)

<strong>Snow at Argenteuil</strong> renders a winter boulevard where light overtakes solid form, turning snow into a luminous field of blues, violets, and pearly pinks. Reddish cart ruts pull the eye toward a faint church spire as small, blue-gray figures persist through the hush. Monet elevates atmosphere to the scene’s <strong>protagonist</strong>, making everyday passage a meditation on time and change <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro turns Paris’s grands boulevards into a river of light and motion. In The Boulevard Montmartre on a Spring Morning, pale roadway, <strong>tender greens</strong>, and <strong>flickering brushwork</strong> fuse crowds, carriages, and iron streetlamps into a single urban current <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. The scene demonstrates Impressionism’s commitment to time, weather, and modern life, distilled through a fixed vantage across a serial project <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning

Camille Pissarro (1897)

From a high hotel window, Camille Pissarro renders Paris as a living system—its Haussmann boulevard dissolving into winter light, its crowds and vehicles fused into a soft, <strong>rhythmic flow</strong>. Broken strokes in cool grays, lilacs, and ochres turn fog, steam, and motion into <strong>texture of time</strong>, dignifying the city’s ordinary morning pulse <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne

Alfred Sisley (1872)

Alfred Sisley's The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne crystallizes the encounter between <strong>modern engineering</strong> and <strong>riverside leisure</strong> under <strong>Impressionist light</strong>. The diagonal suspension bridge, dark pylons, and filigreed truss command the left foreground while small boats skim the Seine, their wakes breaking into shimmering strokes that echo the sky.

The Church at Moret

Alfred Sisley (1894)

Alfred Sisley’s The Church at Moret turns a Flamboyant Gothic façade into a living barometer of light, weather, and time. With <strong>cool blues, lilacs, and warm ochres</strong> laid in broken strokes, the stone seems to breathe as tiny townspeople drift along the street. The work asserts <strong>permanence meeting transience</strong>: a communal monument held steady while the day’s atmosphere endlessly remakes it <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Floor Scrapers

Gustave Caillebotte (1875)

Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers stages three shirtless workers planing a parquet floor as shafts of light pour through an ornate balcony door. The painting fuses <strong>rigorous perspective</strong> with <strong>modern urban labor</strong>, turning curls of wood and raking light into a ledger of time and effort <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. Its cool, gilded interior makes visible how bourgeois elegance is built on bodily work.

The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train

Claude Monet (1877)

Claude Monet’s The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train plunges viewers into a <strong>vapor-filled nave of iron and glass</strong>, where billowing steam, hot lamps, and converging rails forge a drama of industrial modernity. The right-hand locomotive, its red buffer beam glowing, materializes out of a <strong>blue-gray atmospheric envelope</strong>, turning motion and time into visible substance <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Loge

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1874)

Renoir’s The Loge (1874) turns an opera box into a <strong>stage of looking</strong>, where a woman meets our gaze while her companion scans the crowd through binoculars. The painting’s <strong>frame-within-a-frame</strong> and glittering fashion make modern Parisian leisure both alluring and self-conscious, turning spectators into spectacles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Railway

Édouard Manet (1873)

Manet’s The Railway is a charged tableau of <strong>modern life</strong>: a composed woman confronts us while a child, bright in <strong>white and blue</strong>, peers through the iron fence toward a cloud of <strong>steam</strong>. The image turns a casual pause at the Gare Saint‑Lazare into a meditation on <strong>spectatorship, separation, and change</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect

Claude Monet (1903 (begun 1900))

Claude Monet’s Waterloo Bridge, Sunlight Effect renders London as a <strong>lilac-blue atmosphere</strong> where form yields to light. The bridge’s stone arches persist as anchors, yet the span dissolves into mist while <strong>flecks of lemon and ember</strong> signal modern traffic crossing a city made weightless <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>. Vertical hints of chimneys haunt the distance, binding industry to beauty as the Thames shimmers with the same notes as the sky <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Related Themes

Related Symbolism Categories

Society

The Society symbolism category charts how nineteenth‑century artists encoded modern social relations—class hierarchy, gendered labor, spectatorship, and leisure—through recurring motifs of dress, gesture, and urban setting that transform everyday bourgeois and working-class life into a legible iconography of modernity.

Urban

Urban symbolism in modern painting transforms streets, stations, and squares into coded fields where infrastructure, light, and crowd dynamics visualize the social logics of the nineteenth- and early twentieth‑century city.

Vision

“Vision” symbols in modern painting mark not only what is seen but how seeing itself becomes a historical, technological, and psychological problem, turning light, reflection, and vantage into active agents of meaning.

Within nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painting, the city ceases to be a mere backdrop for anecdote and emerges as a symbolic system in its own right. “Urbanity” in this sense names not just a location but a mode of life structured by infrastructure: grids of streets, standardized façades, rail networks, theaters, and illuminated boulevards. Artists exploit these forms as semiotic devices that register new conditions of circulation, perception, and sociability. Bridges, gas lamps, train sheds, and crowds operate as a modern iconography—concrete particulars that stand metonymically for the rationalized, collective experience of industrial urban modernity.

A recurrent feature of this iconography is the bridge, which condenses in a single structure the promise and ambivalence of connection. In Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884), bridges span the Seine in the hazy distance, paired with chimneys and boats. Semiotic weight falls on their dual role: literally, they link banks; pictorially, their horizontal and linear forms introduce geometric order into a riverside scene of workers at rest. They signify the infrastructural web binding suburban leisure to industrial labor—the bridge with steam train, in particular, is an emblem of access, the technology that delivers these bathers to the river while reminding the viewer that respite occurs under the constant horizon of production. As symbols, the bridges articulate a modern logic of connection and control, binding bodies into the reach of the city even when they seem removed from it.

Claude Monet similarly mobilizes bridge symbolism in his London series, where the Waterloo Bridge arches and the Thames’s gridded reflections in Houses of Parliament (1903) entwine endurance with flux. The Parliament’s silhouette—Victoria Tower and attendant spires—indexes institutional permanence, yet Monet dissolves its masonry into a vibrating field of peach, mauve, and gold. Here the river’s rectangular flashes of pink, lemon, and icy blue form a grid of light that doubles the architectural order in liquid form. The arches and reflections operate iconographically as a modern counterpart to the church spire or campanile: instead of spiritual transcendence, they signify the secular endurance of infrastructural connection, even as fog and industrial haze render that endurance perceptually unstable. Power is there, but, as the series insists, it is now seen through the mediating envelope of polluted atmosphere.

Urbanity also announces itself through interiors where public life is staged as reciprocal looking. Theater imagery—loge rails, gilded balconies, opera glasses—reconfigures architecture into a social diagram of visibility. In Mary Cassatt’s In the Loge (1878), the gilded balcony curves behind the central woman, its balustrade functioning as a literal and symbolic threshold. Semiotic force lies in how this rail turns the sitter herself into a display, a spectacle framed against the amber, gaslit auditorium. Opera glasses become emblematic tools of looking and social surveillance, signaling who controls the urban gaze. Cassatt complicates this asymmetry: the woman’s raised glasses assert active vision and agency in public space, while a distant male spectator, himself raising opera glasses toward her, exposes the theater as a circuit of mutual observation. The urban interior is thus figured as an arena where spectators are always at risk of becoming spectacles, an insight that resonates with Renoir’s more ostentatious treatment of the opera box in The Loge, and with Degas’s use of abonnés in the wings as a shorthand for male privilege overseeing female labor.

If the theater epitomizes staged visibility, the boulevard epitomizes circulation. Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877) and Camille Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre at Night (1897) are paradigmatic here. Caillebotte’s Haussmann wedge block, with its synchronized windows and roofline, functions semiotically as the imposition of rational geometry onto lived space; the central gas lamppost, painted in sharp green, is at once an infrastructural fact and an icon of standardized urban order. The painting’s optical logic—photographic cropping, the crisp mid-distance receding into atmospheric blur—folds camera vision into the very experience of the street, making the viewer’s own looking part of the city’s rationalization. The pedestrians and umbrella-bearing couple participate in what might be termed “Traffic and Pedestrians (Urban Flow)”: a ceaseless, impersonal motion in which individuals are subordinated to the rhythm of the thoroughfare.

Pissarro radicalizes this conception by turning night itself into a function of infrastructure. In Boulevard Montmartre at Night, electric arc lamps and gaslit shopfronts parse the darkness into distinct strata of light. The cool white orbs in the boulevard’s center line are signals—articulations of municipal control and synchronized time—while the warmer shop windows encode consumption and private pleasure within the public realm. Semiologically, the painting reads as a diagram of modern illumination: different technologies of light map different kinds of social space and desire. Crowds, carriages, and cab lights blur into an almost musical current, so that the city appears less as a collection of stable things than as an organism of flows and pulses. Urbanity here is not a setting but a temporal condition, registered through the modulation of artificial light across rain-slick stone.

Stations and river quays occupy a related symbolic register as nodal points of movement. Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare (1877) crystallizes the iron-and-glass train shed as a secular nave. The V-shaped roof truss funnels the eye toward a luminous, steam-filled core, transforming industrial architecture into a framework of modernity and order. Semiotic emphasis rests on the contrast between rigid girders and dissolving plumes: the shed’s geometry stands for the rational grid of timetables and routes, while the steam figures the volatility of experience within that grid. Passengers and rail workers, rendered as flickering marks, form a “crowd of passengers and workers” whose transience is orchestrated by the hanging station lamps and locomotives’ schedules. The station’s iconography parallels that of the boulevard: both are systems that subsume individual trajectories into an impersonal choreography of modern time.

Bridges, too, become theaters of circulation. Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Pont Neuf Paris (1872) figures the city’s oldest bridge as a civic commons where crowds and carriage traffic are braided into a shared current. The parapet’s repeating curves and a procession of gas lamps rhythmically pace the roadway, while the fluttering tricolor visually ties dispersed errands to national belonging. The bridge parapet doubles the loge rail in Cassatt’s picture: a boundary that turns those who lean upon it into actors on an urban stage. Renoir’s interest lies in cohesion—the idea that urbanity can cradle difference within a visible, sunlit order—whereas Monet and Pissarro emphasize the dissolution of forms into atmosphere and light, suggesting a more fragile or provisional urban coherence.

Across these works, the semiotic field of urbanity evolves from emblematic clarity to atmospheric ambiguity. Early treatments like Renoir’s Pont Neuf and Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day still rely on legible architectonic markers—bridges, wedge blocks, central lampposts—to encode the rationality and promise of the rebuilt city. By the fin de siècle, however, Monet’s Houses of Parliament and the later Venetian canvases such as San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk transpose this urban and architectural iconography into almost pure fields of color and light. Campaniles, spires, and parliamentary towers survive only as dark verticals and their wavering reflections, emblems of continuity whose stability is visibly tested by water and haze. What begins as a confident symbolism of infrastructure and order becomes, by the early twentieth century, a more skeptical meditation on perception: the urban monument endures, but its meaning is inseparable from the atmospheric conditions that veil, color, and at times nearly erase it. Urbanity, in this trajectory, is ultimately figured less as a fixed built environment than as an historically specific way of seeing.