Mortality

The “Mortality” symbolism category in nineteenth‑century painting translates death from theological drama into terse, often secular signs—blood, smoke, wilted flowers, exhausted bodies—through which modern artists register the finitude of life and the procedural, sometimes anonymized character of modern violence.

Member Symbols

Featured Artworks

Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress)

Claude Monet (1866)

Monet’s Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress) turns a full-length portrait into a study of <strong>modern spectacle</strong>. The spotlit emerald-and-black skirt, set against a near-black curtain, makes <strong>fashion</strong> the engine of meaning and the vehicle of status.

Dance at Bougival

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1883)

In Dance at Bougival, Pierre-Auguste Renoir turns a crowded suburban dance into a <strong>private vortex of intimacy</strong>. Rose against ultramarine, skin against shade, and a flare of the woman’s <strong>scarlet bonnet</strong> concentrate the scene’s energy into a single turning moment—modern leisure made palpable as <strong>touch, motion, and light</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

In the Garden

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1885)

In the Garden presents a charged pause in modern leisure: a young couple at a café table under a living arbor of leaves. Their lightly clasped hands and the bouquet on the tabletop signal courtship, while her calm, front-facing gaze checks his lean. Renoir’s flickering brushwork fuses figures and foliage, rendering love as a <strong>transitory, luminous sensation</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Olympia

Édouard Manet (1863 (Salon 1865))

A defiantly contemporary nude confronts the viewer with a steady gaze and a guarded pose, framed by crisp light and luxury trappings. In Olympia, <strong>Édouard Manet</strong> strips myth from the female nude to expose the <strong>modern economy of desire</strong>, power, and looking <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Plum Brandy

Édouard Manet (ca. 1877)

Manet’s Plum Brandy crystallizes a modern pause—an urban <strong>interval of suspended action</strong>—through the idle tilt of a woman’s head, an <strong>unlit cigarette</strong>, and a glass cradling a <strong>plum in amber liquor</strong>. The boxed-in space—marble table, red banquette, and decorative grille—turns a café moment into a stage for <strong>solitude within public life</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Poppies

Claude Monet (1873)

Claude Monet’s Poppies (1873) turns a suburban hillside into a theater of <strong>light, time, and modern leisure</strong>. A red diagonal of poppies counters cool fields and sky, while a woman with a <strong>blue parasol</strong> and a child appear twice along the slope, staging a gentle <strong>echo of moments</strong> rather than a single event <sup>[1]</sup>. The painting asserts sensation over contour, letting broken touches make the day itself the subject.

Portrait of Dr. Gachet

Vincent van Gogh (1890)

Portrait of Dr. Gachet distills Van Gogh’s late ambition for a <strong>modern, psychological portrait</strong> into vibrating color and touch. The sitter’s head sinks into a greenish hand above a <strong>blazing orange-red table</strong>, foxglove sprig nearby, while waves of <strong>cobalt and ultramarine</strong> churn through coat and background. The chromatic clash turns a quiet pose into an <strong>empathic image of fragility and care</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Sunflowers

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is a <strong>yellow-on-yellow</strong> still life that stages a full <strong>cycle of life</strong> in fifteen blooms, from fresh buds to brittle seed heads. The thick impasto, green shocks of stem and bract, and the vase signed <strong>“Vincent”</strong> turn a humble bouquet into an emblem of endurance and fellowship <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

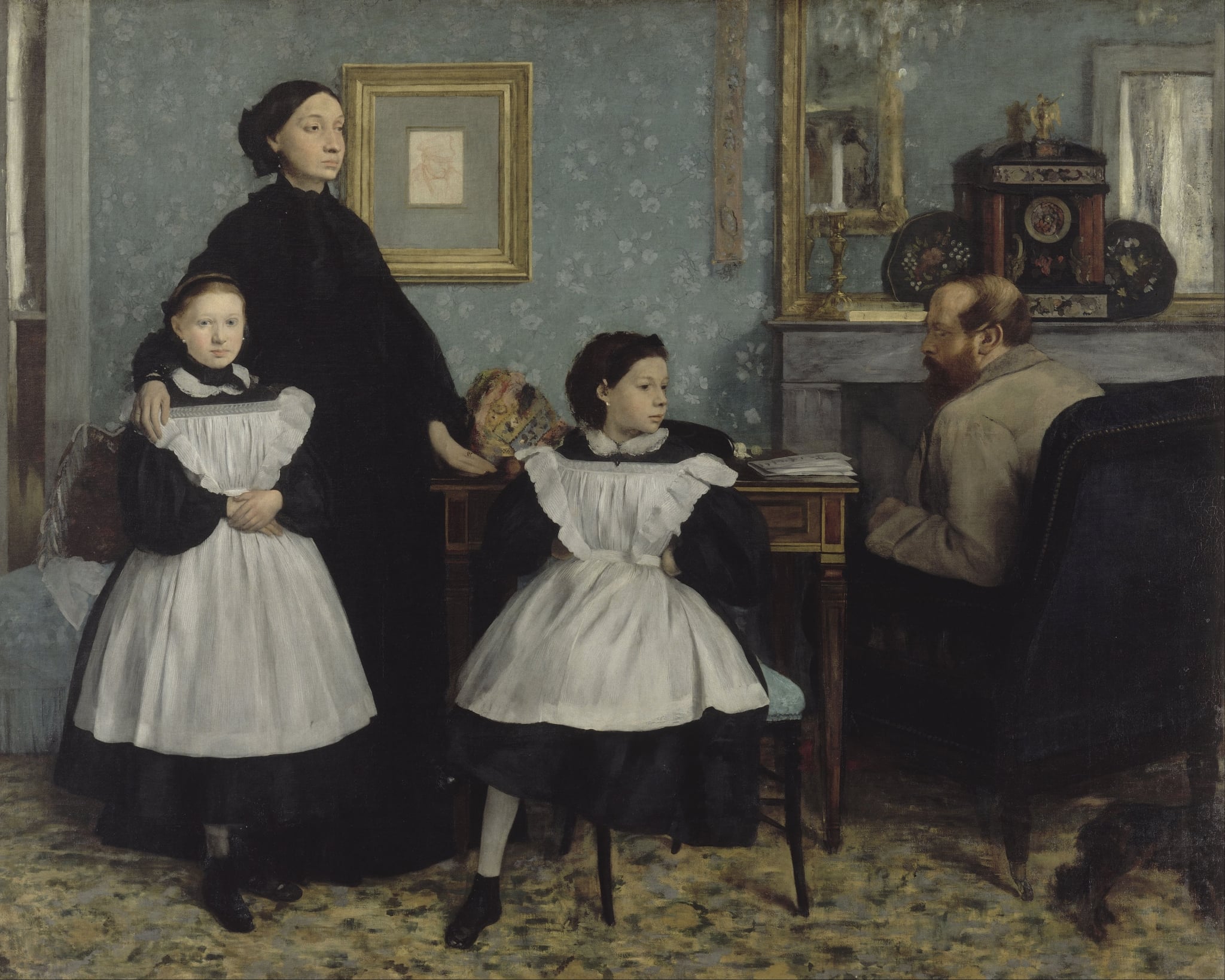

The Bellelli Family

Edgar Degas (1858–1869)

In The Bellelli Family, Edgar Degas orchestrates a poised domestic standoff, using the mother’s column of <strong>mourning black</strong>, the daughters’ <strong>mediating whiteness</strong>, and the father’s turned-away profile to script roles and distance. Rigid furniture lines, a gilt <strong>clock</strong>, and the ancestor’s red-chalk portrait create a stage where time, duty, and inheritance press on a family held in uneasy equilibrium.

The Dead Toreador

Édouard Manet (probably 1864)

Manet’s The Dead Toreador isolates a matador’s corpse in a stark, horizontal close‑up, replacing the spectacle of the bullring with <strong>silence</strong> and <strong>abrupt finality</strong>. Black costume, white stockings, a pale pink cape, the sword’s hilt, and a small <strong>pool of blood</strong> become the painting’s cool, modern vocabulary of death <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Execution of Emperor Maximilian

Édouard Manet (1867–1868)

Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian confronts state violence with a <strong>cool, reportorial</strong> style. The wall of gray-uniformed riflemen, the <strong>fragmented canvas</strong>, and the dispassionate loader at right turn the killing into <strong>impersonal machinery</strong> that implicates the viewer <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Hermitage at Pontoise

Camille Pissarro (ca. 1867)

Camille Pissarro’s The Hermitage at Pontoise shows a hillside village interlaced with <strong>kitchen gardens</strong>, stone houses, and workers bent to their tasks under a <strong>low, cloud-laden sky</strong>. The painting binds human labor to place, staging a quiet counterpoint between <strong>architectural permanence</strong> and the <strong>seasonal flux</strong> of fields and weather <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

The Magpie

Claude Monet (1868–1869)

Claude Monet’s The Magpie turns a winter field into a study of <strong>luminous perception</strong>, where blue-violet shadows articulate snow’s light. A lone <strong>magpie</strong> perched on a wooden gate punctuates the silence, anchoring a scene that balances homestead and open countryside <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Opera Orchestra by Edgar Degas | Analysis

Edgar Degas

In The Opera Orchestra, Degas flips the theater’s hierarchy: the black-clad pit fills the frame while the ballerinas appear only as cropped tutus and legs, glittering above. The diagonal <strong>bassoon</strong> and looming <strong>double bass</strong> marshal a dense field of faces lit by footlights, turning backstage labor into the subject and spectacle into a fragment <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Star

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1878)

Edgar Degas’s The Star shows a prima ballerina caught at the crest of a pose, her tutu a <strong>vaporous flare</strong> against a <strong>murky, tilted stage</strong>. Diagonal floorboards rush beneath her single pointe, while pale, ghostlike dancers linger in the wings, turning triumph into a scene of <strong>radiant isolation</strong> <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[5]</sup>.

Related Themes

Related Symbolism Categories

Humanity

The symbolism of humanity in art encompasses markers of personal connection, social roles, and emotional dynamics, reflecting complex layers of identity and interaction within modern life.

Fashion

In Impressionist and related modern painting, fashion functions as a coded system of class, gender, and spectatorship, translating older allegorical and mythic meanings into the language of couture, accessories, and regulated bodily comportment.

Gesture

Gesture in modern painting operates as a charged system of signs in which the smallest inflection of hand, arm, or posture encodes shifting relations of intimacy, labor, authority, and selfhood, reworking a long iconographic tradition for a newly self-conscious age of looking.

Within the long history of Western art, mortality has shifted from a theologically saturated theme—Last Judgments, martyrdoms, allegorical skeletons—to a field of increasingly minimal, secular signs. By the mid–nineteenth century, painters often refrained from staging death as a grand narrative and instead condensed it into small but charged motifs: a pool of blood, a drooping flower, a weapon turned inert. These details operate within a vanitas lineage, yet their function is newly sober and reportorial. Rather than directing viewers toward salvation or damnation, they insist on the blunt, unredeemed fact of cessation and the procedures by which modern states and institutions administer violence and care.

Manet’s The Dead Toreador (probably 1864) offers a paradigmatic instance of this modern condensation of meaning. The canvas suppresses the arena’s spectacle—bull, crowd, architecture—in favor of a horizontal close‑up of the matador’s corpse. Here, the pool of blood near the head functions as the work’s most overt sign of mortality. Carefully controlled in scale and chroma, it barely spreads, its cool red tonality rhyming with the pale pink of the collapsed cape. This is not Baroque gore meant to evoke pathos; it is a small, clinical punctuation that turns drama into a fact. The blood’s restraint matches the painting’s compositional austerity: by reducing the narrative to a body and its minimal trace of wounding, Manet makes cessation itself the subject. Death is not allegorized but registered.

Equally telling is the painting’s sword hilt, braced against the dead man’s shoulder. As long as the toreador is alive, the sword is an instrument of agency and spectacle; in death, it becomes a mute prop. Its oblique thrust into the picture plane now underscores futility rather than prowess. Semiologically, the weapon’s continued presence insists on the continuity between the role the figure once played and the body he has become, yet that continuity is emptied of efficacy. The hilt’s polished curves and decorative guard are still meticulously rendered, but the thing they guaranteed—action, mastery—is no longer possible. Weapon and blood thus form a paired syntax of mortality: one marks the end of agency, the other the end of circulation.

Other motifs in the same symbolic family render mortality less as an isolated event than as a routinized procedure. The figures of the loader preparing the coup de grâce and the wall of riflemen (backs turned), though not elaborated in the surviving fragment of Manet’s larger bullfight composition, belong to a broader nineteenth‑century visual vocabulary in which killing is shown as protocol. The loader, absorbed in the mechanical “finishing act,” typifies the transformation of death into a task on a chain of operations; the wall of riflemen, their backs turned and faces suppressed, transforms agents into interchangeable functionaries of the state. Both motifs echo the logic at work in the toreador’s reduced body: individuality is subordinated to role, and mortality appears as a consequence of systems rather than of heroic single combats. The anonymity of the firing squad, in particular, displaces moral responsibility from persons to formations, making the very absence of faces a sign of modern, bureaucratized violence.

If Manet’s repertoire of blood and weapons gives mortality a stark, forensic cast, Vincent van Gogh’s still‑life imagery rearticulates the same question in terms of organic time. In Sunflowers (1888), drooping sunflowers appear alongside buds and full blooms, turning a bouquet into a ledger of temporal states. The downward tilt of the withered heads, their browning petals and heavy disks, recall the traditional vanitas flower yet are stripped of explicit religious attributes—no skull, hourglass, or extinguished candle. Instead, the very morphology of the plant bears the message. The droop is not an anecdotal accident but a structural sign of decline within a tightly orchestrated chromatic world. Yellow decays into ocher and burnt gold, and this shift in hue parallels the passage from vitality to exhaustion. Mortality here is cyclical and comparative: the dying heads gain their full poignancy by proximity to fresher blooms.

The same painting thus juxtaposes two temporalities of mortality against the abrupt cessation marked in The Dead Toreador. In Manet, the body’s stillness and the tidy pool of blood present death as an instant. In Van Gogh, the sunflower’s stooping arc and desiccated texture present it as a slow bending toward the inevitable. Yet these images share a crucial semiotic strategy: both displace moral commentary into facture and form. Manet’s tight editing—the excision of crowd and bull—amounts to an ethics of framing, while Van Gogh’s impasto and near‑monochrome palette force the eye to read minute variations in yellow as stages of life’s wearing down. Neither requires explicit allegorical figures; mortality is legible in the way color and matter are handled.

Even when death is not literally depicted, several motifs in this symbolic group orbit mortality as a constant horizon. The puffs of gun smoke that sometimes fringe scenes of execution operate as a cool, almost journalistic trace. Like the unlit cigarette in Manet’s Plum Brandy, smoke is an index of combustion, but here the combustion has already entered its lethal phase. The smoke’s lightness and dispersion stand in uneasy counterpoint to the heaviness of the bodies it will soon bring down; its neutrality of form underlines how little the visual world changes when lives end. Similarly, the figure of the loader preparing the coup de grâce suggests that the final shot is neither climactic nor visually privileged: it is one more step in a sequence. Both motifs register what we might call the routinization of mortality—the way modern images show killing as a process rather than a sublime rupture.

Across these works, a network of echoes emerges. The pool of blood beneath Manet’s toreador answers to the darker, seed‑laden centers of Van Gogh’s most exhausted sunflowers: both are small, intense zones where life’s circulation is either emptied or transformed. The sword hilt’s useless gleam corresponds to the brittle, downward spokes of burned‑out petals: objects and organisms equally outlive their vital function. And the anonymous collective power of the riflemen finds its vegetal analogue in the bouquet’s crowded heads, where no single flower dominates the narrative; what matters is the cycle as a whole.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, these symbols chart a movement from overtly moralizing vanitas to a more analytical, sometimes dispassionate visualization of finitude. Earlier allegories personified Death; Manet trims it to a stain and an idle weapon, while Van Gogh folds it into the sag of a stem and the thickening of paint. Mortality is no longer a separate figure invading the scene, but an immanent condition legible in procedures, systems, and the material world itself. In this sense, the era’s mortuary symbols participate fully in the project of modern art: to relocate ultimate themes from the realm of transcendent narrative into the visible, contingent surfaces of everyday life.