Light

Light in this corpus operates as a symbolic medium that translates technological, atmospheric, and chromatic conditions into reflections on modern perception, social experience, and the temporality of vision.

Member Symbols

Featured Artworks

Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Camille Pissarro (1897)

A high window turns Paris into a flowing current: in Boulevard Montmartre at Night, Camille Pissarro fuses <strong>modern light</strong> and <strong>urban movement</strong> into a single, restless rhythm. Cool electric halos and warm gaslit windows shimmer across rain‑slick stone, where carriages and crowds dissolve into <strong>pulse-like blurs</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Café Terrace at Night

Vincent van Gogh (1888)

In Café Terrace at Night, Vincent van Gogh turns nocturne into <strong>luminous color</strong>: a gas‑lit terrace glows in yellows and oranges against a deep <strong>ultramarine sky</strong> pricked with stars. By building night “<strong>without black</strong>,” he stages a vivid encounter between human sociability and the vastness overhead <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress)

Claude Monet (1866)

Monet’s Camille (The Woman in the Green Dress) turns a full-length portrait into a study of <strong>modern spectacle</strong>. The spotlit emerald-and-black skirt, set against a near-black curtain, makes <strong>fashion</strong> the engine of meaning and the vehicle of status.

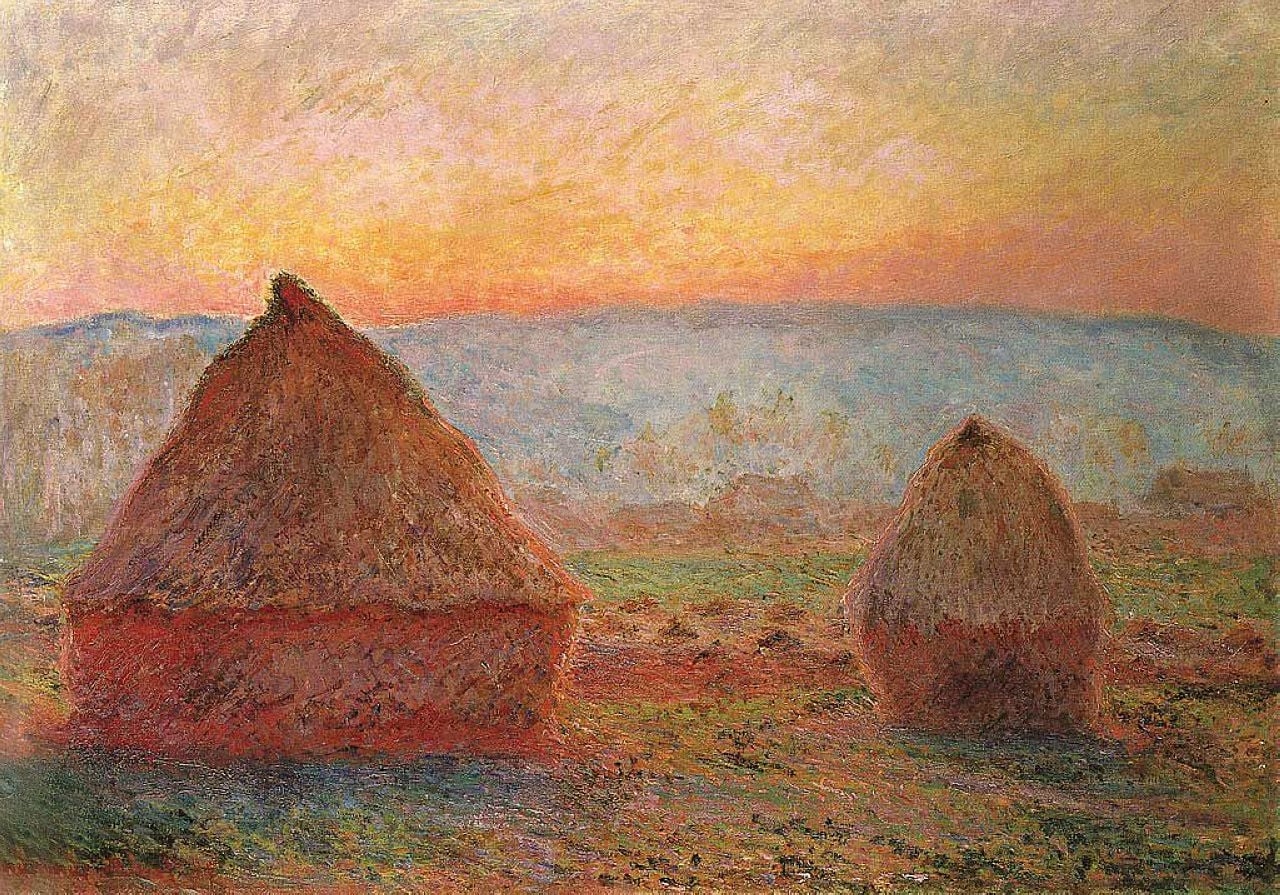

Haystack, Sunset

Claude Monet (1891)

Two conical stacks blaze against a cooling horizon, turning stored grain into a drama of <strong>light, time, and rural wealth</strong>. Monet’s broken strokes fuse warm oranges and cool violets so the stacks seem to glow from within, embodying the <strong>transience</strong> of a single sunset and the <strong>endurance</strong> of agrarian cycles <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>.

Haystacks Series by Claude Monet | Light, Time & Atmosphere

Claude Monet

Claude Monet’s <strong>Haystacks Series</strong> transforms a routine rural subject into an inquiry into <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunset view, the stacks swell at the left while the sun burns through the gap, making the field shimmer with <strong>apricot, lilac, and blue</strong> vibrations.

Houses of Parliament

Claude Monet (1903)

Claude Monet’s Houses of Parliament renders Westminster as a <strong>dissolving silhouette</strong> in a wash of peach, mauve, and pale gold, where stone and river are leveled by <strong>luminous fog</strong>. Short, vibrating strokes turn architecture into <strong>atmosphere</strong>, while a tiny boat anchors human scale amid the monumental scene.

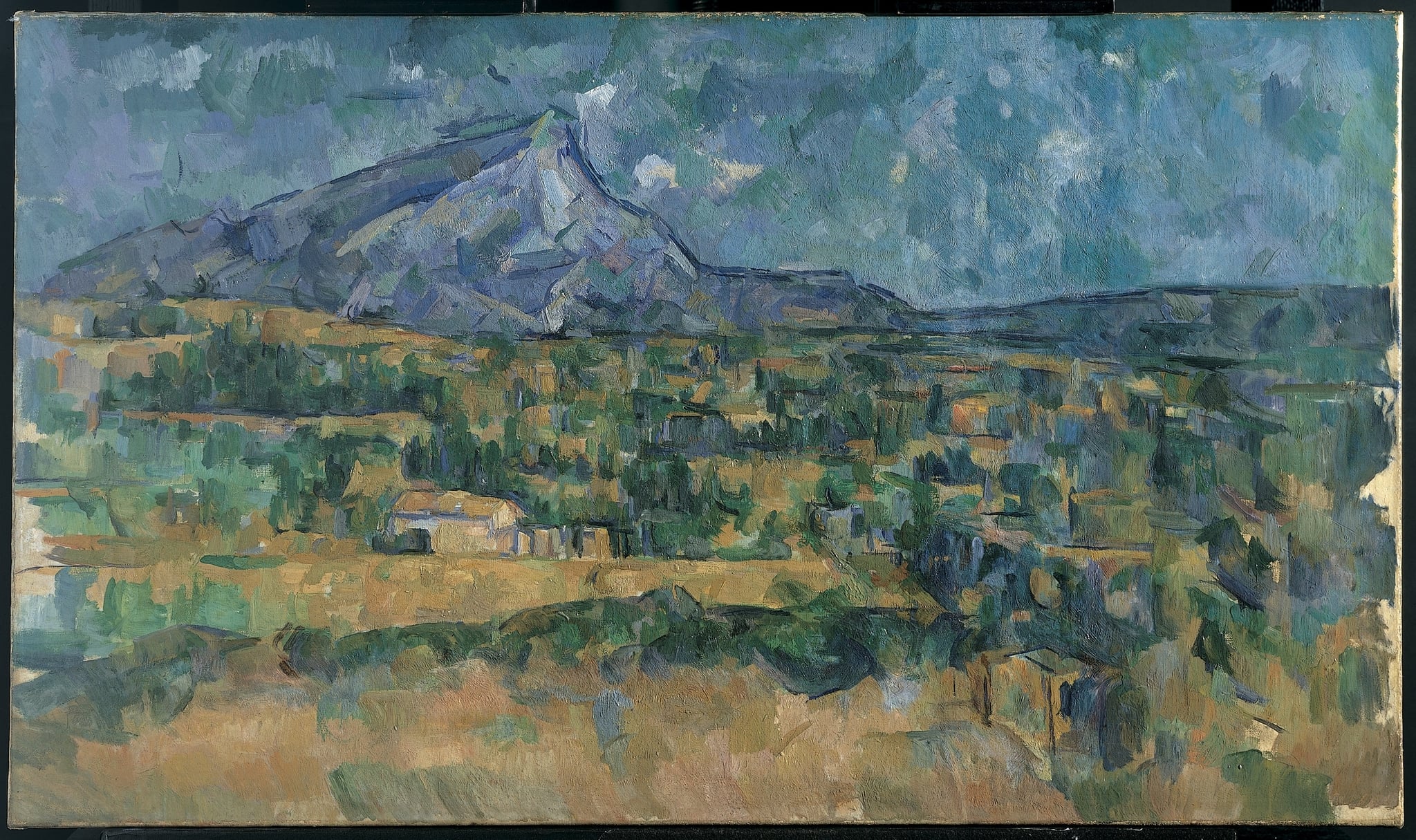

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Paul Cézanne (1902–1906)

Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire renders the Provençal massif as a constructed order of <strong>planes and color</strong>, not a fleeting impression. Cool blues and violets articulate the mountain’s facets, while <strong>ochres and greens</strong> laminate the fields and blocky houses, binding atmosphere and form into a single structure <sup>[2]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Morning on the Seine (series)

Claude Monet (1897)

Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine (series) turns dawn into an inquiry about <strong>perception</strong> and <strong>time</strong>. In this canvas, the left bank’s shadowed foliage dissolves into lavender mist while a pale radiance opens at right, fusing sky and water into a single, reflective field <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Nighthawks

Edward Hopper (1942)

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks turns a corner diner into a sealed stage where <strong>fluorescent light</strong> and <strong>curved glass</strong> hold four figures in suspended time. The empty streets and the “PHILLIES” cigar sign sharpen the sense of <strong>urban solitude</strong> while hinting at wartime vigilance. The result is a cool, lucid image of modern life: illuminated, open to view, and emotionally out of reach.

Poplars on the Epte

Claude Monet (1891)

Claude Monet’s Poplars on the Epte turns a modest river bend into a meditation on <strong>time, light, and perception</strong>. Upright trunks register as steady <strong>vertical chords</strong>, while their broken, shimmering reflections loosen form into <strong>pure sensation</strong>. The image stages a tension between <strong>order and flux</strong> that anchors the series within Impressionism’s core aims <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Red Roofs

Camille Pissarro (1877)

In Red Roofs, Camille Pissarro knits village and hillside into a single living fabric through a <strong>screen of winter trees</strong> and vibrating, tactile brushwork. The warm <strong>red-tiled roofs</strong> act as chromatic anchors within a cool, silvery atmosphere, asserting human shelter as part of nature’s rhythm rather than its negation <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. The composition’s <strong>parallel planes</strong> and color echoes reveal a deliberate structural order that anticipates Post‑Impressionist concerns <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Rouen Cathedral Series

Claude Monet (1894)

Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedral Series (1892–94) turns a Gothic monument into a laboratory of <strong>light, time, and perception</strong>. In this sunstruck façade, portals, gables, and a warm, orange-tinged rose window flicker in pearly violets and buttery yellows against a crystalline blue sky, while tiny figures at the base anchor the scale. The painting insists that <strong>light—not stone—is the true subject</strong> <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

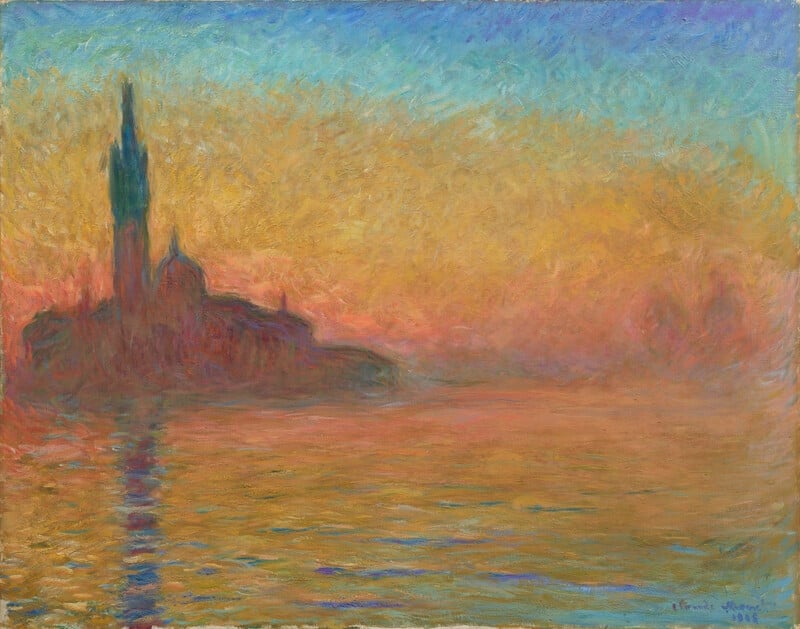

San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk

Claude Monet (1908–1912)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk fuses the Benedictine church’s dark silhouette with a sky flaming from apricot to cobalt, turning architecture into atmosphere. The campanile’s vertical and its wavering reflection anchor a sea of trembling color, staging a meditation on <strong>permanence</strong> and <strong>flux</strong>.

San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight

Claude Monet (1908)

Claude Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore by Twilight turns Venice into a <strong>luminous threshold</strong> where stone, air, and water merge. The dark, melting silhouette of the church and its vertical reflection anchor a field of <strong>apricot–rose–violet</strong> light that drifts into cool turquoise, making permanence feel provisional <sup>[1]</sup>. Monet’s subject is not the monument, but the <strong>enveloppe</strong> of atmosphere that momentarily creates it <sup>[4]</sup>.

The Cliff, Etretat

Claude Monet (1882–1883)

<strong>The Cliff, Etretat</strong> stages a confrontation between <strong>permanence and flux</strong>: the dark mass of the arch and needle holds like a monument while ripples of coral, green, and blue light skate across the water. The low <strong>solar disk</strong> fixes the instant, and Monet’s fractured strokes make the sea and sky feel like time itself turning toward dusk. The arch reads as a <strong>threshold</strong>—an opening to the unknown that organizes vision and meaning <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Floor Scrapers

Gustave Caillebotte (1875)

Gustave Caillebotte’s The Floor Scrapers stages three shirtless workers planing a parquet floor as shafts of light pour through an ornate balcony door. The painting fuses <strong>rigorous perspective</strong> with <strong>modern urban labor</strong>, turning curls of wood and raking light into a ledger of time and effort <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup>. Its cool, gilded interior makes visible how bourgeois elegance is built on bodily work.

The Opera Orchestra by Edgar Degas | Analysis

Edgar Degas

In The Opera Orchestra, Degas flips the theater’s hierarchy: the black-clad pit fills the frame while the ballerinas appear only as cropped tutus and legs, glittering above. The diagonal <strong>bassoon</strong> and looming <strong>double bass</strong> marshal a dense field of faces lit by footlights, turning backstage labor into the subject and spectacle into a fragment <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Woman Ironing

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1887)

In Woman Ironing, Degas builds a modern icon of labor through <strong>contre‑jour</strong> light and a forceful diagonal from shoulder to iron. The worker’s silhouette, red-brown dress, and the cool, steamy whites around her turn repetition into <strong>ritualized transformation</strong>—wrinkled cloth to crisp order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

Woman with a Parasol

Claude Monet (1875)

Claude Monet’s Woman with a Parasol fixes a breezy hillside instant in high, shifting light, setting a figure beneath a <strong>green parasol</strong> against a vast, vibrating sky. The low vantage and <strong>broken brushwork</strong> merge dress, clouds, and grasses into one atmosphere, while a child at the rise anchors depth and intimacy <sup>[1]</sup>. It is a manifesto of <strong>plein-air</strong> perception—painting the sensation of air in motion rather than the contours of things <sup>[2]</sup>.

Related Themes

Related Symbolism Categories

Vision

“Vision” symbols in modern painting mark not only what is seen but how seeing itself becomes a historical, technological, and psychological problem, turning light, reflection, and vantage into active agents of meaning.

Color

Color symbolism in art history encapsulates emotional intensity, cultural nuance, and artistic experimentation, with artists leveraging hues to convey complex narratives and atmospheres.

Objects

In modern painting, everyday objects become charged mediators of vision, labor, desire, and time, replacing inherited allegories with a material, self-conscious language of modern life.

Within the long history of Western art, light moves from a primarily theological and metaphysical signifier—divine radiance, revelation, or grace—to an analytic instrument for describing perception, environment, and social modernity. The works assembled in this category register that shift with particular clarity. Here light is not only illumination but also a means of thinking: it measures time, articulates technological change, stages public display, and redefines the relations between individuals and their urban or rural surroundings. The accompanying symbols track how artists convert specific conditions of light—electric glare, atmospheric haze, chromatic afterglow—into legible structures of meaning.

Many of these symbols treat light as an organizing field rather than a mere source. In Claude Monet’s Morning on the Seine series, the river at dawn is rendered as a chromatic field mosaic and a silvery enveloppe of haze. The definition of the former—“nature infused by light; unity of environment where shadow becomes color”—is borne out in the almost seamless fusion of bank, water, and mist. Monet cancels the horizon so that reflection and reality become indistinguishable, enacting the idea that early light converts discrete objects into a single atmospheric continuum. The “silvery enveloppe” likewise “merges city and sky; meaning in the air between things,” a logic that directly informs Houses of Parliament, where the Gothic mass dissolves into mauve and pale gold. In both cases, authority—whether of the built environment or of solid form itself—is relativized by an enveloping light that insists on relational seeing.

This environmental conception of light intersects with more explicitly temporal symbols. Haystack, Sunset and the broader Haystacks series are structured by a solar disk and sunset corona, figures that denote “the moment of day turning toward dusk” and “fleeting time and transience.” In the sunset view where the sun wedges between two monumental stacks, Monet converts stored grain—rural wealth and continuity—into a screen for ephemerality. The triangular blaze of yellow that “dissolves contour and turns shadow into color” functions iconographically as a concentrated measure of time; it is less a represented orb than a temporal wedge that reorganizes every relation of warm to cool. Here, symbols such as shattered light on water—“flux and transience; time registered as flickering sensation”—are latent: the field and sky are broken into vibrating strokes that make the very stability of the stacks dependent on unstable, passing light. These canvases underscore a central semiotic shift: luminosity no longer signals timeless divinity but the measurable, even precarious, passage of hours and seasons.

By contrast, urban nocturnes such as Camille Pissarro’s Boulevard Montmartre at Night and Vincent van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night treat light as a modern technology that reorders social space. Pissarro’s Parisian boulevard is structured by electric arc lamps and rain-slick reflections. The arc lamps—“modern civic technology and order; cold, regulated illumination of the metropolis”—form a beaded chain of cool white orbs, a new, rational grid imposed on the nineteenth-century city. Their spectral regularity differs from the warmer, broken gaslit windows at shop level, a distinction the artist renders through subtle tonal and chromatic shifts. Below, rain turns the boulevard into a reflective plane: “transformation and doubling of urban light; spectacle created by weather and technology.” The reflections do not merely duplicate; they liquefy the technological order above, suggesting that even this rationalized illumination is subject to chance and flux. Van Gogh’s Arles street scene, by contrast, builds a nocturne “without black.” Its ultramarine starry sky—“the vast, ordered cosmos; night as luminous presence rather than absence”—hovers above an incandescent café defined by a proto-symbolist spotlight and pool of light. The sulphur-yellow lantern casts a localized halo of belonging that competes with the cool, blue avenue of risk. Here, celestial order and terrestrial hospitality are staged as chromatic antitheses rather than theologically continuous realms, marking a secular reconfiguration of the old contrast between heavenly and earthly light.

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks radicalizes this technological strand by making artificial light itself the dominant subject. The diner’s interior is flooded with fluorescent light, “clinical illumination and modern technology that clarifies yet cools emotion; a beacon without warmth.” Hopper’s description underscores how this light “bleaches color toward the greenish end of the spectrum,” draining both figures and objects of sensual richness. Semiotically, fluorescent glare becomes a sign of late modern rationality—uniform, efficient, and emotionally disenchanting. The curved glass of the diner intensifies the effect of a spotlight and pool of light: interior space is overexposed, while the surrounding streets recede into a dark, under-articulated void. Yet unlike the café in Van Gogh, this pool of illumination does not connote sociability; it codifies isolation under observation. The public glare that “turns surface into meaning” here renders the figures legible but unreachable, suggesting surveillance rather than communion.

Across these works, atmospheric and technological treatments of light converge on a shared concern with mediation. Monet’s Houses of Parliament stages London’s power center through a “luminous fog/smog”—“modernity’s air that dissolves form and equalizes elements.” The institution appears as a dark, vertical accent within a broader silvery enveloppe of haze that visually democratizes stone, sky, and river. This is a politicized form of light: by leveling materials into tone, it tacitly contests monumental solidity. Pissarro’s Paris, too, is seen through a veiling atmosphere—cool halos diffused by moisture—while the arc lamps and gaslights offer competing regimes of visibility. In both cases, air itself carries history and technology: London’s pollution-tinted haze and Paris’s municipal lighting infrastructures inscribe industrial modernity into the very medium of seeing.

Finally, in Paul Cézanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire, light ceases to be episodic or spectacular and becomes structural. The sky is described as a structural sky, “air treated as a constructive medium, not backdrop—space made of interlocking planes.” Cool blues and blue-grays echo the mountain’s faceting, so that illumination is not a transient overlay but an intrinsic condition of form. Here the symbol of a diffused sun—“source of vision and illumination; a leveling force turning stone into tone”—is implicit. No solar disk appears, yet every plane is calibrated through warm–cool modulations that posit a constant, rationally distributed light. Iconographically, the massif becomes less a Romantic emblem of nature’s sublimity than an analytic paradigm, an object through which to understand how light organizes volume over time.

Taken together, these images trace an evolution from sacral or allegorical light to secular, situated, and often technologically inflected luminosity. Where earlier traditions anchored meaning in stable hierarchies—divine beams, halos, or emblematic suns—late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painters in this corpus treat light as contingent, plural, and historically specific. Electric lamps, fluorescent tubes, fogbanks, and chromatic fields do not abolish symbolic content; they displace it. Illumination now encodes shifting social orders, emergent infrastructures, and the historicity of perception itself. In this sense, the symbols gathered under “Light” do not merely catalogue effects; they chart a modern conviction that how the world is lit—by sun, gas, electricity, or haze—is inseparable from what the world means.